You know how some people are obsessed with stamp collections or fantasy football teams? Well, we're obsessed with cookbooks. Here, in Books We Love, we'll talk about our favorites.

Today: Travel through the rich history of southern food with Marcie Cohen Ferris.

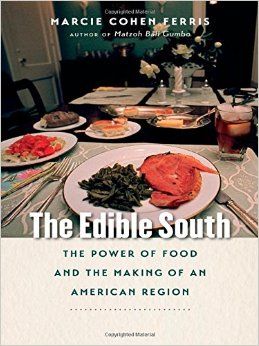

The power in Marcie Cohen Ferris’ new book, The Edible South: The Power of Food and the Making of an American Region, comes from the voices within its pages. In covering 500 years of Southern history, Ferris, an associate professor of American Studies at the University of North Carolina, searched archival letters, journals, and other correspondence, so that the people who lived and ate in the South across many eras could tell their stories themselves.

Early travelers and settlers describe the land and its bounty, even as they grappled with starvation; young white women from New England working as nannies write home to their families, trying to convey the taste of a peach dessert; slave narratives collected by the WPA recount daily deprivation and terror. It’s often a story of haves and have-nots.

“Throughout Southern history,” Ferris writes in the introduction, “the politics of power and place has established a regional cuisine of both privilege and deprivation that continues to impact the daily food patterns of southerners today.”

More: Here are 6 ways to make your kitchen more southern.

That connection -- that answer to how we got there from here -- is what makes this book so necessary. Ferris doesn’t flinch from the sorrows of the plantation era or those of the Jim Crow era, but she doesn't linger there, either. She continues sharing important voices up to the current moment, when Southern chefs such as Vivian Howard and Hugh Acheson, among others, have circled back to the local and the seasonal, and when the South has led the nation in both celebrating its regional cuisine and facing its often painful origins.

Along the way, Ferris provides answers to questions that have long perplexed us: Why has Southern food often been dismissed as inherently unhealthy? How did the same forces that led to malnutrition in one generation encourage obesity in the next? What other food stories does the South have to tell?

In the plantation era, the Southern diet was focused on in-season vegetables and little meat, but only white landowners had access to it. In the sharecropping era, vast quantities of land were planted with two inedible crops: cotton and tobacco. Tenant farmers were often forced to plant cotton “up to their doorstep,” forbidden to plant a kitchen garden, and thus had to buy foodstuffs from their landlords. More recently, the counterculture movement brought about several “intentional communities” in the South, including The Farm in Summertown, Tennessee.

Some bare realities Cohen reveals are cringe-inducing: A slave child caught stealing a peppermint candy is punished by having the bones in her face crushed under a rocking chair's rails, condemning her to a lifetime of being unable to chew solid food. Others are fascinating: The first commercial soy ice cream, “Ice Bean,” was developed at The Farm.

Southern chefs elevating local ingredients began in the 1970s when the late Bill Neal (a native of South Carolina) and his wife Moreton (a native of Mississippi) opened both La Residence and Crook’s Corner in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The Neals partnered with small-scale farmers to create a local terroir. Many celebrated chefs came through those two kitchens and went on to create landmark restaurants of their own. At the same time, chef Edna Lewis, who had introduced her New York City clientele to the foods of her childhood in Virginia, published her memoir-cookbook, The Taste of Country Cooking.

More: Learn how to make hush puppies at home.

Food writer Nathalie Dupree continued and broadened this movement by writing cookbooks and appearing on a public television series, "New Southern Cooking with Nathalie Dupree," which was underwritten by the White Lily Flour company of Knoxville, Tennessee. Many writers and cooks searched for better-quality and better-tasting food than what industrial agriculture and mass production brought.

“Today,” Ferris concludes, “the longing for an authentic agrarian southern past that people can literally taste has been ‘born again’ in the local food movement and activism of southern chefs, farmers, artisan entrepreneurs, food writers, and scholars.”

We have Ferris, a scholar, to thank for connecting the dots in this wonderful book. It is for anyone who is interested in basic American history -- in facing our shared past, so we can keep moving toward a healthier and more inclusive future.

First and last photos by James Ransom; all others provided by University of North Carolina Press

See what other Food52 readers are saying.