The Story Behind Flag Cake—& Why It Is (and Isn’t) as Silly as It Seems

Ina Garten thinks that she invented flag cake.

And she may as well have. Of the more than two and a half million results that come up when you Google the phrase, her recipe—which makes an 18- by 13-inch sponge cake topped with cream cheese frosting and fresh blueberries and raspberries—is the first.

(Martha Stewart might take issue with Ina’s claim. "I was definitely one of the first to make a flag cake—if not the first. We used the cake for a prototype issue of my magazine 25 years ago," she wrote to me in an email—okay, she dictated to a P.R. account executive, who wrote it to me in an email.)

But back to basics Ina. “It’s kind of silly,” she told me on the phone: “I think I just made it up.” She doesn’t remember seeing it anywhere else—not in books or magazines or on other websites—before she started selling it out of her specialty food store in the Hamptons one year for the Fourth of July. She’d limit the order to fifty per summer, keeping tabs on each one. “People went berserk and it became a tradition.”

And when she published it in Barefoot Contessa Family Style in 2002 and demoed it on her Food Network show for the “All American” episode the next year, “it somehow became a thing.” So much of a thing that Taylor Swift made it—twice. On Brit and Co., the flag cake was called “Taylor Swift’s”: As in, “You Need to Make Taylor Swift’s Flag Cake for 4th of July.” And so the flag cake—which, let’s be clear, is a cake representation of the American flag, a symbol of our country, an object that we salute and serenade—could then be semantically confused with a cake decorated with the flag of Taylor Swift. The flag cake is no longer Ina Garten’s, and it’s certainly not the United States’.

Today’s flag cake is a free agent, a dessert that’s removed from the flag itself and as related—or as entirely unrelated—to the Fourth of July and the values it represents as we make it out to be. And it’s a dessert that’s much more complex—and much older—than Ina (or, for that matter, Martha) knows.

We can credit Ina for catapulting the berry-striped flag cake to the status of extremely Pin-able Fourth of July dessert, sure, but she wasn’t the first one to make it.

Best-selling author Anne Byrn researched it for her forthcoming book American Cake but ultimately decided it didn’t earn a place among the 115 classic recipes: “It was sort of a gimmicky cake,” she told me—especially in comparison to the patriotic “Election Cake” that existed before the American Revolution (and well over two hundred years before flag cake as we know it). These heavily spiced, enriched yeast-risen cakes were originally baked, according to Cake: A Global History, by inns and homekeepers to feed farmers who came into town for military training and, after independence, to cast their ballots.

During the first half of the 19th century, there were also patriotic cakes “named or renamed to express patriotism in the new nation”: plenty of cakes devoted to George Washington, and one for Andrew Jackson and Zachary Taylor, too. As Mark Zanger writes in The American History Cookbook, these cakes were meant to “patriotically commemorate fallen leaders” rather than to assume political stances. In this era before representational cake-baking became popular, there’s little to distinguish the cakes aesthetically—and there’s no immediate connection between the person and the baked good.

Like what you're reading?

Sign up for our newsletters to get more long reads, recipes, and the most-loved picks from our shop (patriotic or not).

Even during the Civil War, when “a series of warring political cakes that commemorated Northern and Southern heroes and political positions” emerged, it might have been hard to distinguish Lincoln Cake from General Gordon Cake (named after the Georgian confederate hero) in a line-up. The latter was not adorned with a giant Confederate flag. (You’ll have to fast forward to 2015 for that.)

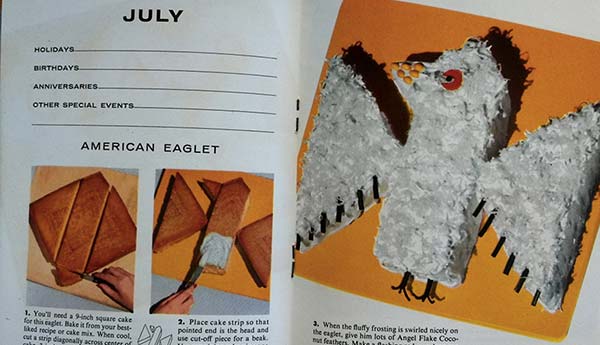

Later on, in the early 1900s, patriotic desserts were more likely to be petit-fours, frosted with a light icing and carefully painted blue and red with dye made from indigo and dried beetle. In the years during World War I and World War II, flag cakes were baked to lift spirits—not reserved to commemorate Independence Day or Washington’s birthday—and, before mid-century, they did not mimic the flag itself. The 1940 recipe for Independence Day Cake from the Frederick News Post produces a multi-layer cake with pink frosting and unspecified Fourth of July “ornaments” around the base.

A few years earlier, in 1934, there’s a similarly simple Fourth of July cake in 50 Cakes for 50 Occasions. Following two more elaborate cakes—a Colonial Cream Cake with candied cherries for Washington’s birthday (“decorate the edges with candied cherries and small chocolate hatchets”) and a Log Cabin Cake for Lincoln’s (a “cardboard chimney may be inserted at one end and covered with icing”)—is the relatively plain Raspberry Torte, a “colorful dessert for this, our most colorful national holiday!”

And again, in 1937’s Holidays and Holiday Meals, it’s the holidays that most of us barely acknowledge today (Washington’s and Lincoln’s birthdays) that receive special attention—and patriotic significance: The author recommends a cherry tree centerpiece, which “never loses its appeal for a George Washington party." No flag cake here.

As for the July Fourth showstopper we know today, Anne doesn’t think it existed until the early 1950s, “and that was in an Associated Press story that used a white cake mix spread with strawberries.”

Anne’s research fits with culinary historians Laura Shapiro’s and Stephen Schmidt’s speculations: Neither know the history of the cake specifically, but both surmise that it was either invented by or capitalized on by companies—manufacturers of cake mixes and flours, or distributors of berries, perhaps—and popularized in promotional newsletters, women’s magazines, and newspapers. Behind the flag cake, as behind so many cultural phenomena in our capitalist country, there is the motivation of money.

And yet the 1955 recipe for “A Flag Cake!” in the Cleveland Call and Post, which calls for Instant Swans Down Yellow Cake Mix, still emphasizes patriotism at its core: "A patriotic dessert? But definitely! And a luscious one to be enjoyed by every patriot present!" And a July 1959 recipe in the Atlanta Constitution promises “to earn you the title of ‘Betsy Ross of the Kitchen’”; the number of stripes and stars are inaccurate, but that the headnote even points that out is itself an indication that these symbols are more than a pattern of yellow cake and chocolate custard: Acknowledging a mistake gives weight to what’s right. In both cases, making the cake—and eating it, too—is an act of patriotism, even with the commercial bend.

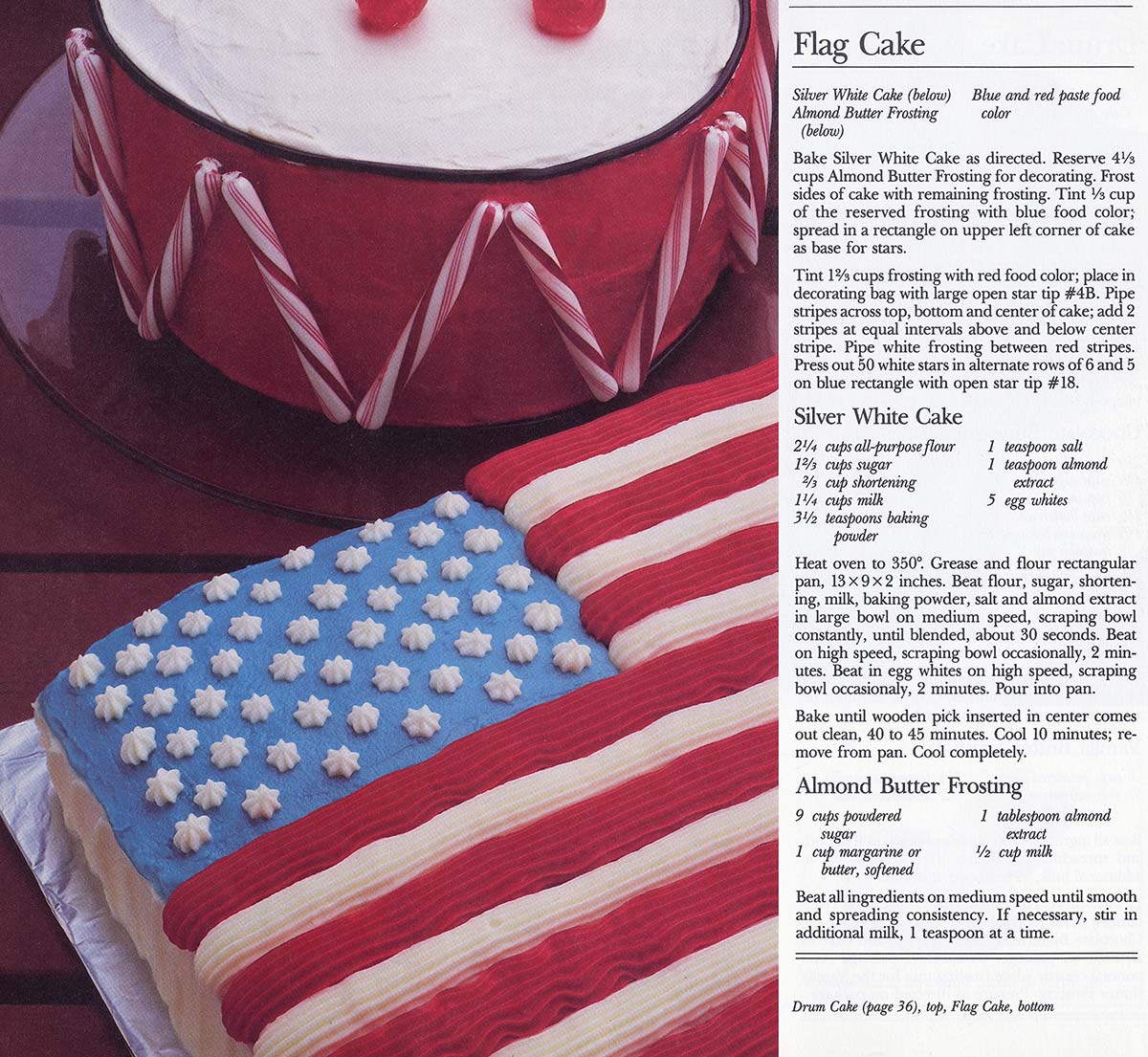

The same is true of the 1984 debut of the first Betty Crocker recipe (pictured above) in Betty Crocker’s Cake Decorating with Cake Recipes for Every Occasion cookbook; it’s a from-scratch cake with Almond Butter Frosting (not made of almond butter, as you’d expect on any one of today’s wellness blogs, but rather, American buttercream flavored with almond extract) with detailed decorating instructions: “Press out 50 white stars in alternate rows of 6 and 5 on blue rectangle with open star tip #18.” Even if the language of patriotism isn’t present, the idea of creating the flag’s likeness, of thinking, even subconsciously, about what each one of the fifty stars and thirteen stripes represents, is present. It’s a learning experience, intentional or not.

Compare that to 2016, when there are at least fourteen Betty Crocker flag cakes published online; the group includes Red, White, and Blue Poke Cake; Cake Ball Flag Cake; and Fireworks Push-it-Up Cakes (I couldn’t make that name up!), as well as “firecracker” dishes (like the Firecracker Pancakes, which are topped with a patriotic “red, white, and blue glaze” that looks, quite frankly, like what Uncle Sam might vomit up). These red, white, and blue desserts—some of Betty Crocker’s most popular summer content—all call for various commercial products, like Betty Crocker™ SuperMoist™ white cake mix or Betty Crocker™ Rich & Creamy vanilla frosting. Where once we had cakes to honor President Washington in name rather than gaudy decoration, we now have “flags” constructed from a seemingly random number of spheres of crumbled cake that’s been mushed with frosting and dipped into liquefied “candy melts” (“cake balls”). Is it supposed to evoke reverence for our country, or is it what Anne Byrn meant when she told me of the the cake’s “downhill spiral”?

Today, there’s no-bake flag cheesecake; there’s fruit flag pizza; there’s (very impressive-looking) flag pie; there’s flag cake cobbled in M&Ms; there’s flag cake roulade. And when you’ve had your fill of cake, look at the “Flag Cake Skewers” made of berries and marshmallows (“No slicing or serving utensils needed for this flag cake,” the tagline reads) and flag platters made of berries and cheese. And that’s before you go down the rabbithole of patriotic non-flag foods (like red, white, and blue deviled eggs and cheesecake-stuffed strawberries).

This isn’t the first time or the only place people have eaten flags: On a somber note, Hitler’s 1937 birthday cake was frosted with a giant swastika; on a happier one, Danes eat dannebrogskage on their Constitution Day (June 5th), each slice a miniature flag. But the ubiquitousness of the American flag cake—and its allegiance to industry, rather than politics—seems unique.

Anne’s characterization of the current cake as a gimmick—a stronger version of Ina’s gentle admission that it’s “silly”—seems undeniable. We’ve come a long way since resource-intensive fruit cakes, painstakingly-painted petit-fours, fifty perfectly piped stars.

And, putting aside the question of whether flag cakes—the kind with a random number of stars and stripes; the kind created to generate page views, to optimize search results (that was the motivation behind Eating Well's 2013 cake, their digital director Michelle Edelbaum told me), or to sell products; the kind so far removed from the flag and what it symbolizes historically—are still patriotic, there’s another looming question: Do these things even taste good, or are they for looks and looks alone?

Somewhere along the way, we’ve forgotten flag cake is a flag and we’ve also forgotten it’s a cake. For eating. “But come on, really: If we’re going to create a cake that epitomizes our country, we need a better cake,” Anne Byrn concluded at the end of our conversation.

And we don’t have our country’s most expert bakers on the case. Neither Dorie Greenspan, Joanne Chang, Alice Medrich, nor Rose Levy Beranbaum knew anything about it. Dorie told me that she’s sure she’s “seen this cake on magazine covers ever since [she] was old enough to pay attention to such things” (perhaps disputing both Ina’s and Martha’s statements?), but none of these great cake-makers had tried her hand.

Deb Perelman of Smitten Kitchen, who made one of the most attractive versions back in 2012, pre-Taylor Swift, was motivated by the desire for a cake weighed down with July’s berries, and she developed the recipe so that it would taste as good as possible: “Basically, and I feel this way about any food that’s also decorative, it should be objectively good. Who cares if it looks like a flag if it tastes like nothing but frosting? Pretty food doesn’t actually taste better.”

In the end, the flag cake—even one topped with berries instead of gelatin—is, in the words of Food52’s controller Victoria Maynard “just a sad-looking sheet cake” once all the fruit is gone. Victoria learned that the hard way (and now makes a good layer cake instead, limiting her flag consumption to fruit kebabs, “like our forefathers intended”).

The flag cake we posted on this site in 2014, and again in 2015, aimed to solve that problem. It’s a visual surprise, and there are no berries to leave a soggy mess after they’ve been cherry-picked by a greedy guest. It also tastes good, as I can attest. (I can also say with confidence that Deb’s flag cake tastes good, even after the berries have been pilfered—we made, and photographed, it for this article.)

And yet, when I look at it, I think more about the incredible skill of Erin McDowell, who baked it (but, she wants it to be known, did not conceive of the idea)—and whether I could do it myself, and whether my friends would be impressed (would my friends be impressed?!)—than I do about our country.

The proliferation of flag cakes on Pinterest, the use of our national flag to sell products and generate attention, is annoying but predictable. It’s capitalism: We try to sell everything. We invent “holidays” for the sole purpose of making money (see: Negroni Week) and Food52 is not above this (buy our flag products below!) and our own epic flag cake brings readers to our site—and revenue to our company—every year.

To me, it’s tacky but harmless. I’d make a flag cake! It’s fun to be tacky. Tackiness is, partly, what America’s about! (Ina might disagree; so might you.) And as our photographer Bobbi Lin sweetly put it, "anything represented in a cake is a form love and reverence!” (Well, not that Hitler cake.)

When we sent out our “We pledge allegiance to the picnic. (And to the United States of potato salad.)” email with a photo of a picnic on the American flag wool throw, we upset a fair amount of email subscribers: the flag (there was no clear indication that it was a blanket) was on the floor, it was being sat on, it was being used as a commercial item, it was a violation of the U.S. Flag Code, which states:

The flag should never touch anything beneath it, such as the ground, the floor, water, or merchandise.

But eating a flag cake is not offensive, perhaps because it’s already so far removed from any political implications. People who might not normally hang a flag in their windows or recite the Pledge of Allegiance or put a flag bumper sticker on their car might still make a flag cake (and then post it to Instagram). I would! We forget what the flag means—how it’s meant hope and justice to so many groups of people, the opposite of that to plenty of others— when it’s in cake form. It’s kitsch; it’s colors and lines. And, to get philosophical, it’s an emotional ingestion: We eat as an act of representation all the time—communion wafers at Catholic church, charoset at the Jewish Passover Seder.

Except then there are times when we choose to remember what it means. Flag Cake made national headlines in July of last year, when a Wal-Mart in Slidell, Louisiana refused to fill an order for a Confederate flag cake, yet decorated another with the ISIS flag for the same customer, who had returned to the business to prove a point. Wal-Mart issued a statement that local staff did not recognize the black and white flag.

And so flag cake—a commercialized arm of our Fourth of July holiday, the equivalent of heaps of candies and singing cards on Valentine’s Day, devoid of all meaning at this point—became the battleground for a debate about freedom of expression, a platform for discussing when symbols are blatantly hateful (the ISIS and Nazi flags) and when they’re historical matter. Who decides that? Must bakeries honor business transactions for Confederate flag cakes? Or can they use their First Amendment rights to deny a request they find morally repugnant? If they make Confederate flag cakes, must they make gay pride flag cakes also?

The silly gimmick is more relevant to current conversations—to the present-day debates centered on documents that our nation’s independence gave way to—than we give it credit for. It’s got some meaning after all.

It might be more patriotic, in the truest sense of the word, to support local farmers this holiday, to bake something to bring to the post office, or the fire department, or a veterans’ hospital; instead, we’ll make camp in our kitchens and bake cakes as beautiful as we can; those that will get us the most attention on Instagram; or, in the world of food media, the most page views.

But this country’s all about the can-do, take-what-you-can-get, fight-to-the-top sort of attitude. Who are we if not people who work with what we have, make the most of what’s there, use symbols and resources to our own advantage (in a sometimes terrible, exploitative, or just plain dumb way)?

Maybe a flag cake isn’t the most patriotic of cakes—maybe it’s not a symbol of our forefathers’ and foremothers’ struggle for freedom (or a symbol of all those since then who have struggled—and continue to fight—to be free)—but it’s a symbol of the U.S. in all of our wackiness, our gimmicks, our commercialism, our fun, our complexity, our wrongheadedness, our humor. Our commitment to freedom of expression. Even if that expression is dictated to us by large corporations trying to sell their products. Even if that commitment leads to rancorous debate.

And what’s more patriotic than that?

Like what you read?

Sign up for our newsletters to get more long reads, recipes, and the most-loved picks from our shop (patriotic or not).