We love all the products in our Shop, but some inspire us to dig a little deeper as to their origins.

Today: Inspired by our newest kitchen apron -- a Studiopatró design by Christina Weber in a fresh springy blue -- we're taking a look at the history of apron fashions and the origins of familiar modern designs.

Our new apron from Studiopatró is as popular with pro kitchen crews as home cooks -- it's lightweight, with pocket and towel loops right where you need them.

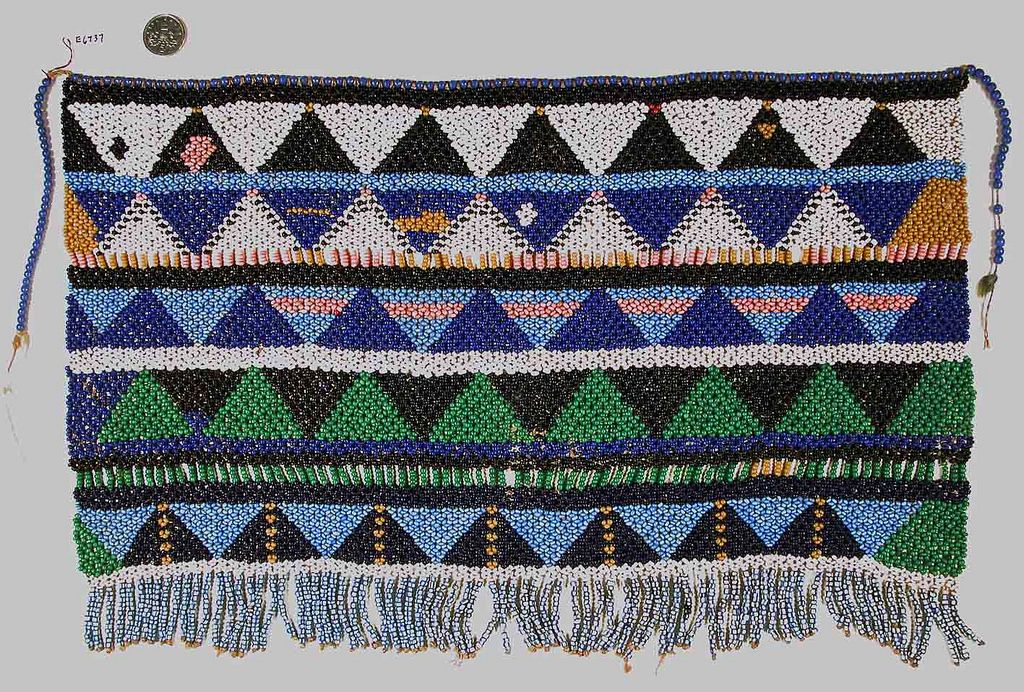

The earliest aprons weren't used to protect clean blouses from spaghetti sauce splatters; they were actually just loincloths, and some cultures still prize them for uses unrelated to cooking. Japanese sumo wrestlers, for example, wear a type of apron called kesho mawashi, a garment that dates back to the Edo period, and in contemporary South Africa, young women wear beaded aprons to celebrate their coming of age.

South African apron, ca. 1896, via the Cooper Hewitt Museum; South African beaded apron, possibly Malawi, via the Smith Art Gallery and Museum

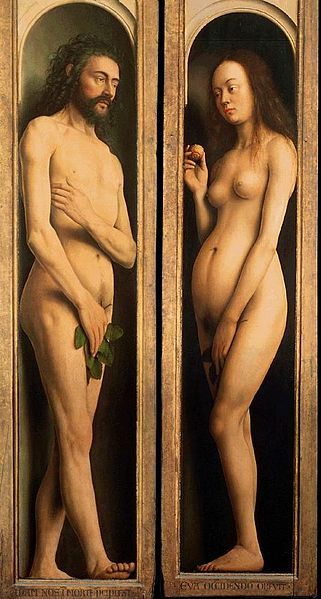

Putting a finger on the exact date that aprons were invented is pretty near impossible -- but there's a good chance that apron-style garments were actually the first clothing ever worn. Some claim they have biblical beginnings, that when Adam and Eve fled the Garden of Eden they were wearing aprons made of fig leaves.

But when we talk about modern American apron designs, protecting one's clothing is the garment's main purpose. (And we're thankful for it!) After all, the word apron has the same root as napkin (from the French word nappe). They're not just giant bibs, though -- aprons are also decorative, with designs that have evolved alongside fashion trends. Findings at Minoan archaeological sites in Crete show one of the earliest examples of an apron that's layered over garments: Fertility goddess figurines dating from around 1600 BCE depict females wearing aprons, possibly indicating how women of the time dressed.

Adam and Eve from the Ghent Altarpiece (detail), by Jan van Eyck (circa 1390–1441), 1432, via Wikimedia Commons; Snake goddess, by C messier, is licensed under CC 4.0 International

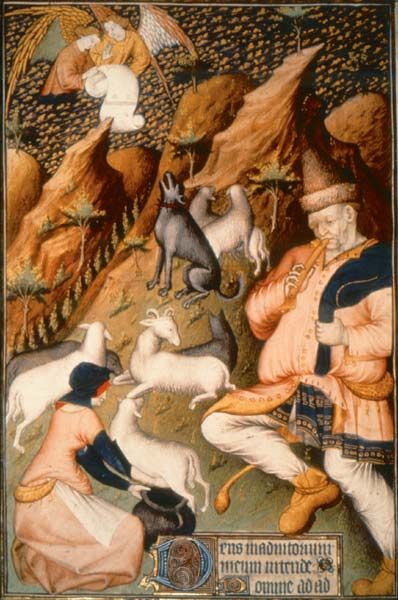

Fast-forward a few thousand years, to when aprons were simple garments favored by the working class in Europe. Medieval aprons in this tradition were a humble affair, often white linen flaps attached at the waistband with drawstrings or tucked into mens' belts, depicted in manuscripts and artwork from the time. The upper-body bib we know and love on aprons today? That design was developed to better protect craftsman at work.

A shepherdess in the Rohan Hours, c. 1430-1435, via BNF Lat. 9471, fol. 85v; Bavarian Stonemasons, by Rueland Frueauf the Younger (1470–1545), 1505 via Wikimedia Commons

Male artisans and workmen relied heavily on aprons, and the design often distinguished a particular trade. 16th century English barbers were known as “checkered apron men,” while cobblers wore “black flag” aprons, and gardeners, spinners, weavers and garbage men all wore blue aprons. London porters in the 18th-century wore green. Even today, white aprons are incorporated as part of Masonic ceremonial attire as a nod to the white aprons of early stonemasons.

More: Our new blue Studiopatró apron works for gardeners, too.

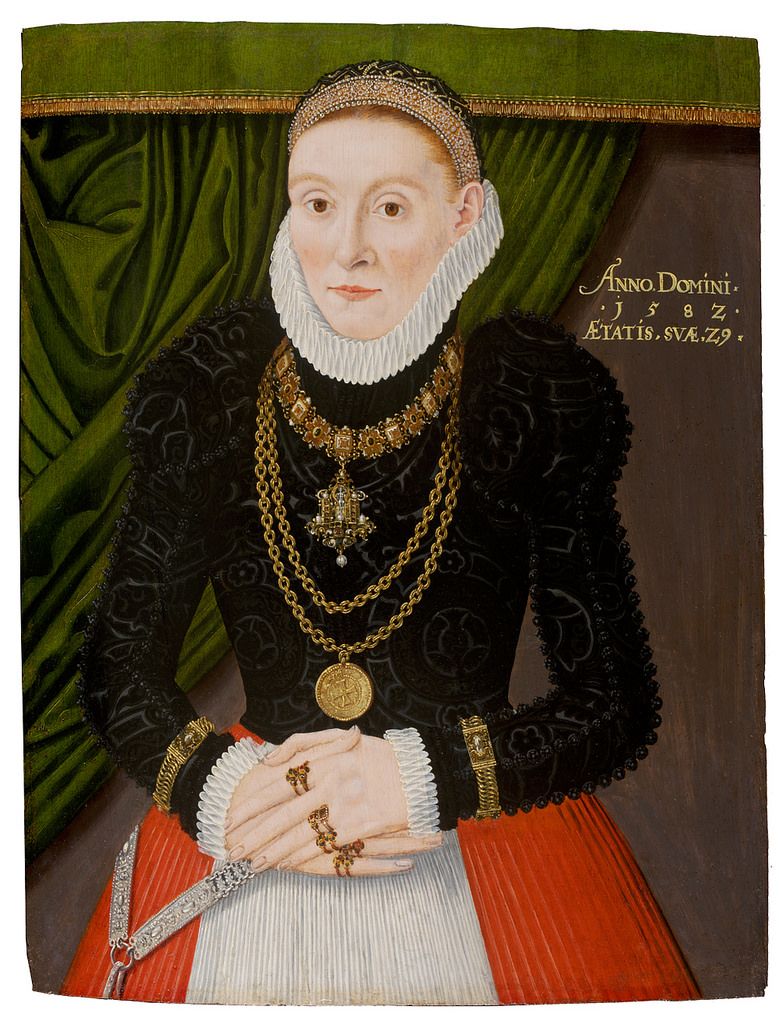

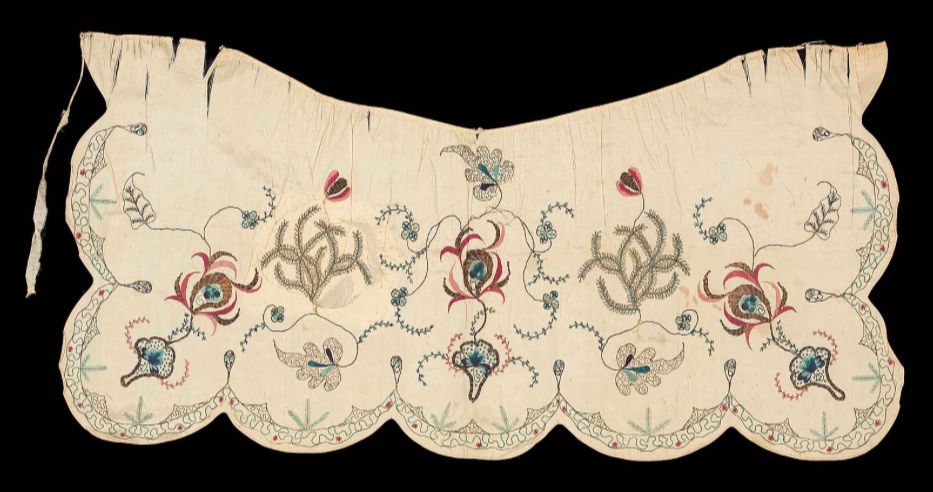

From these utiliarian beginnings, the modern apron got more stylish over time. During the Renaissance, more fanciful aprons crafted from finer fabrics began to appear -- usually without bibs and often embroidered. Well-to-do women favored long dresses often with detachable sleeves, and to keep their expensive gowns clean, they wore washable aprons or overdresses in a range of embellishments and materials.

Oil portrait of a 29-year old woman, artist unknown, north-west Germany, 1582, via Victoria & Albert Museum; English-style gown with a decorative silk gauze apron, 1760, via Victoria & Albert Museum

Embroidered Italian apron, late 16th- to early 17th-century, via Museum of Fine Arts Boston; French apron, 18th century, metal and lace with gold metallic threads, via Museum of Fine Arts Boston

In Victorian England, at the height of the industrial revolution, the market was flooded different types of aprons. The boom of factories and sewing machines meant that consumers had options: You could choose a full-body apron, a linen apron, a linen apron with ruffles or ruching or lace, a grosgrain apron with embroidery, or an apron with a flounce.

In addition to being a growing consumer society, Victorian England was also quite a hierarchical one. There are stories of housemaids who were instructed to turn and face the wall when they passed their employers in the hallway. Aprons were a way of indicating the difference in status between the employer and the employee, and the uniform of the staff was strictly regulated. For example, a housemaid might wear a print dress during the day and then change into a black dress and dress apron for the evening service.

Paper doll, England, c. 1830 via Victoria & Albert Museum; Copeland & Lye Christmas catalog page, 1909, via Glasgow City Archives

Stateside, aprons were a part of local culture before the Pilgrims even docked: American indians wore aprons for both practical and ceremonial purposes. Later, early settlers from England wore plain long white aprons, often gathering a corner into their belt to create a stylish drape, and Quaker women wore brightly-colored aprons. As cities in New England grew, more elaborate options began to appear. Classy American women in the 18th century wore embroidered aprons that sometimes dipped at the front of the waist (so as to not obscure the bodice of the gown).

Shaman's dance apron, from the Nisga'a tribe, c. 1870, via National Museum of the American Indian; Embroidered apron, 18th-century New England, silk with silk and gold metal embroidery, via Museum of Fine Arts Boston

When there wasn't much fabric to be had during the Great Depression, women would fashion aprons and other clothes out of grain sacks. Pinafore aprons called “pinnies” gained popularity around this time, made famous by Dorothy's iconic blue and white gingham version in the 1939 film the Wizard of Oz.

Cross-back apron design, 1920s, via Wikipedia; Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale, wearing her famous pinafore, in the 1939 film the Wizard of Oz via The Daily Mail

Often when we think about modern apron design, we’re transported to the 1950s, when aprons became the symbol of the housewife thanks to stylish TV moms like June Cleaver and Donna Reed. The full covered apron skirts of the period were a sign to Americans that the war was over and women were home in the kitchen. However, husbands in the 1950s weren’t immune to the apron-wearing fashion -- they often sported styles made just for barbeques on the weekends.

Apron designs by Bonnie Cashin (American, Oakland, CA), 1955 and 1950, respectively, via the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Apron designs by Bonnie Cashin (American, Oakland, CA), 1955 and 1950, respectively, via the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The sentiment that made the apron so popular in the 1950's made it less popular in the 60s and 70s, when traditional gender roles began to shift. In recent years, apron designs have become simpler and more unisex, with a nod to craft rather than a gendered view of housework. As in years past, the best apron designs are a marriage of comfort, protection, and fashions of the time.

Our new exclusive apron from Studiopatró works hard to protect you and couldn't be prettier.

See what other Food52 readers are saying.