The first time I tried Ghat Tasmi was in a home in Geblen, a village in far northern Ethiopia. It had been a hot day, but the dark brought a chill that drove my host family and me around a small charcoal stove.

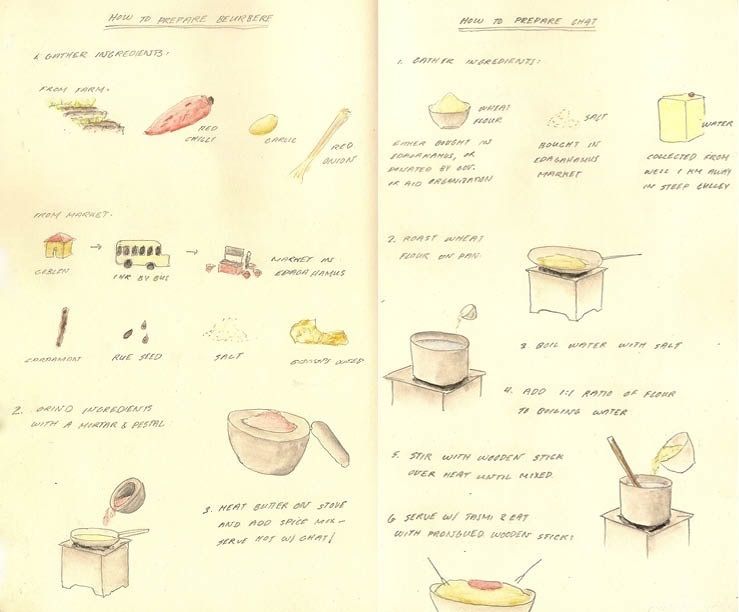

An illustration of the preparation of Ghat Tasmi from a page of the author's journal.

An illustration of the preparation of Ghat Tasmi from a page of the author's journal.

Khasa Desta, my host mother, took a pot and washed it carefully, using as little water as she possibly could to clean it (every drop of water is precious and a laborious task to collect). She then boiled water and slowly added flour to the pot from a large sack supplied through the government food aid program. Using a stick, she mixed the dough until it became smooth and sticky.

Setting it aside, she put another pan on the charcoal and added a large chunk of freshly-made butter. When the butter started to smoke, she poured in a generous amount of berbere, a spicy blend of chiles and local herbs that makes your eyes water if you came within a three feet of it. Khasa Desta then poured the mixture into a hole she had pressed in the center of the pot of dough. The smell of spices drifted out into the courtyard and my host father and brother joined us, squatting on small wooden stools around the stove. We ate with pronged sticks from the communal pot until our bellies were full and our bodies warmed.

Ghat Tasmi was just one of the extremely unfamiliar dishes I tried this past year, a list that includes live sago grubs (a species of beetle larva) in Borneo, roasted monkey in the Peruvian Amazon, goat intestine in the lower-Omo Valley in Ethiopia, and reindeer in northern Siberia. Over the course of one year, I lived in seventeen mostly-rural communities in Borneo, Peru, Ethiopia, and Siberia, where people have developed dozens of recipes using just a handful of ingredients available to them. I traveled to these regions to report on how development is impacting the housing security of indigenous peoples, and came away with a more nuanced understanding of the intersection between food culture and changing livelihoods.

Dinner tables have never been more different than they are now.

Dinner tables have never been more different than they are now.

Traditionally, cultures have been created by their resources (both natural and designed), but global supply chains and advanced agricultural technology have allowed us to access nearly every food imaginable from all over the world. The Japanese eat urchins caught only hours earlier off the coast of Maine, the French import bananas from equatorial Africa, and Chinese food manufacturers rely on palm oil from Brazil for their processed foods. One could easily pose the question: What does food culture even mean in a world where products—and people—are so mixed around? What food culture do you belong to when you cook “Indian-fusion” on Tuesday night, “Mexican” on Thursday, and “Norwegian” pancakes on Sunday morning?

Tribal cultures, on the other hand, are often seen as one monolith, as if they were all hunter-gatherers eating fish, jungle meat, and wild fruit. But this could not be farther from the truth. Today, due to a lack of lands and resources, as well as climate change, there are very few “pure” hunter-gatherer societies left. Most are now in a stage of transition, forced to give up their traditional livelihoods and food cultures and begin farming, or if their land is too degraded, move into urban areas where they will eat what is affordable at the local market. The “indigenous” table today covers a spectrum of diets, some of which are laid out below:

Agro-Hunting-Gathering

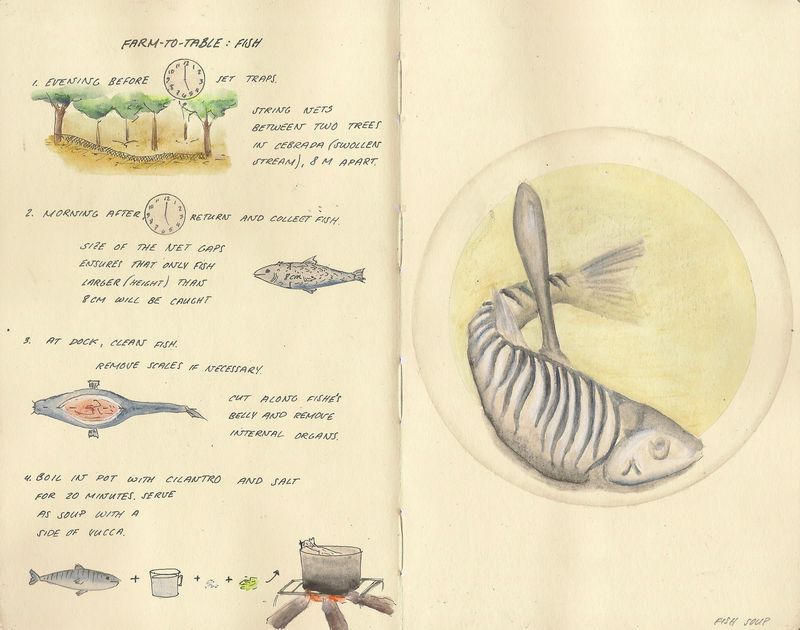

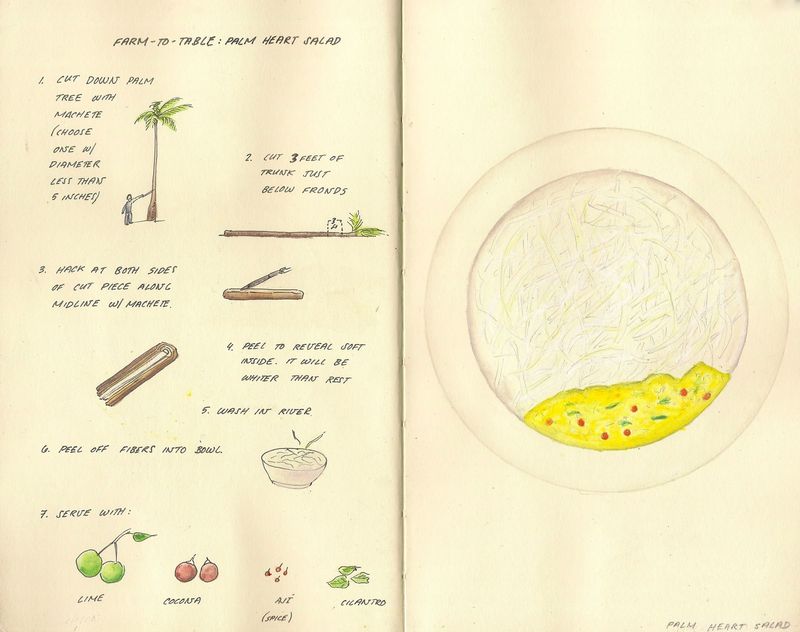

Left: The process of preparing fish soup in Peru. Right: Tree-to-table palm heart salad in Peru.

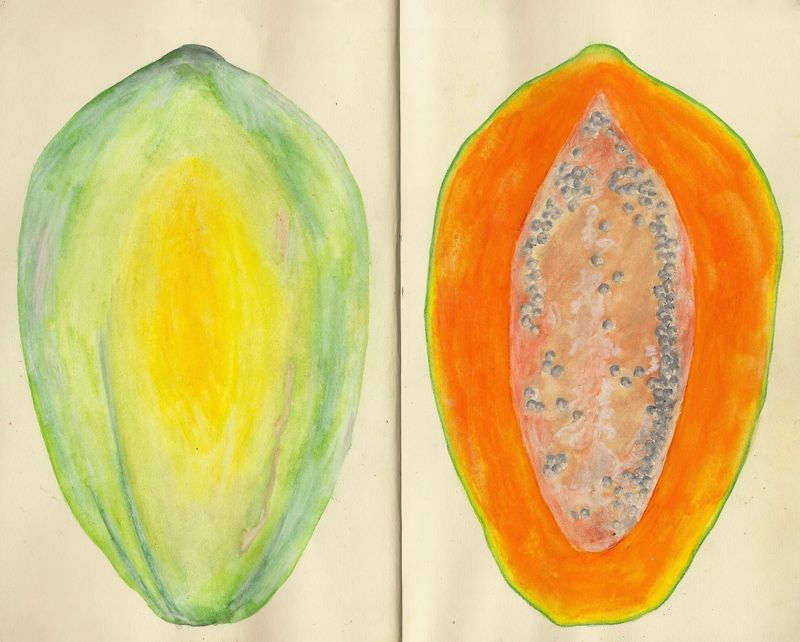

Many of the tribes I stayed with have been pressured into practicing subsistence agriculture, either because of villagization by missionaries or governments, or because environmental degradation has eliminated their food sources as hunter-gatherers. For example, the Matses in the Peruvian Amazon grow a variety of crops (plantain, yucca, papaya, and maize) and they also fish, hunt for birds, and collect wild fruit. By diversifying their modes of production, they are resilient to social and environmental pressures that might otherwise make them food insecure.

Agro-Pastoral

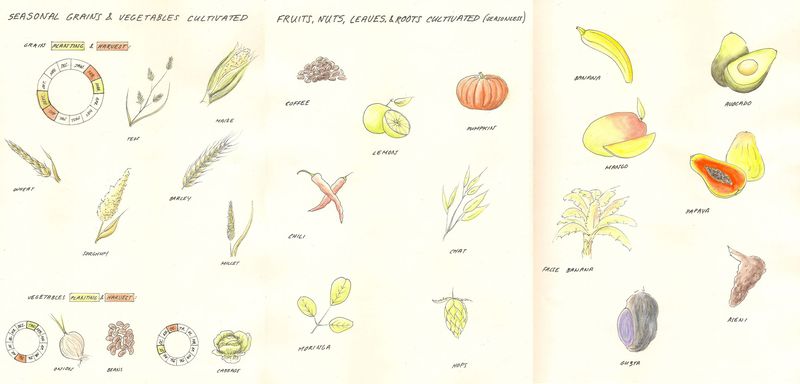

Foods grown by the Ari Tribe in Omo Valley, Ethiopia

This is a sustainable diet in principle as people can substitute the crops they grow with meat from their herds. The problem is that in practice, most agro-pastoralists live in areas that suffer from perpetual drought, so their livestock are dying. People are also hesitant to eat their livestock because it is seen as throwing away their life investment. Many of the tribes in Ethiopia’s Omo Valley were once only pastoral and have now begun farming cereals (often maize and sorghum) as developers take more and more of their grazing land.

Urban

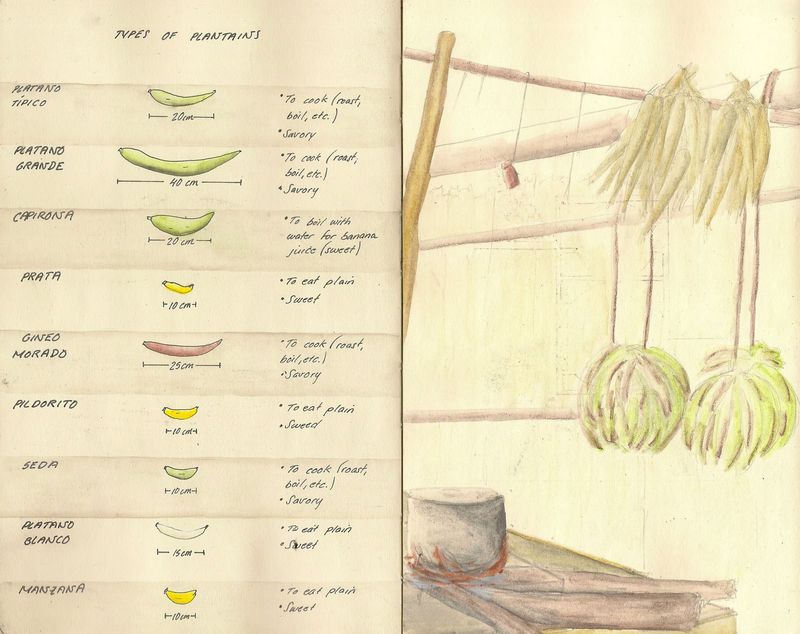

Left: Different types of plantains in Peru; Right: The most beautiful papaya.

By far, the indigenous communities with the greatest food insecurity I met this year were those who have urbanized. They are no longer autonomous in their food production and rely on what is available and affordable at the markets in the urban settlements they live in. Many, like the Aymara of El Alto, Bolivia, eat only potatoes, rice, spaghetti, and fried chicken. They may be getting enough food, but the quality is contributing to severe health issues including obesity, diabetes, and nutrient deficiency.

In visiting such a diverse range of communities and learning about their changing food cultures, I came to better understand that our demands for certain foods have environmental and social consequences on where they are grown and produced. This doesn't mean we have to change the entire system, but whether it's shopping at your local farmers market more often, or checking the place of origin on those strawberries, every bit counts towards keeping our world's cultures vibrant and people secure.

Serves 4

For the sauce:

8 teaspoons dried red chile powder

2 teaspoons minced garlic (approximately 3 cloves)

1 red onion

1/2 teaspoon cardamom

1/2 teaspoon rue seed (substitute nutmeg if unavailable)

1/2 cup butter

1 tablespoon salt

For the ghat:

2 cups unrefined whole wheat flour

1 tablespoon salt

2 cups water

See the full recipe (and save and print it) here.

To see more recipes and other drawings from Mayrah's trip, visit “Writing + Publications”on www.mayrahudvardi.com.

All illustrations by Mayrah Udvardi

See what other Food52 readers are saying.