We're sitting down with our favorite writers and cooks to talk about their upcoming cookbooks, their best food memories, and just about anything else.

Today: René Redzepi, chef of Noma in Copenhagen and author of the new cookbook A Work in Progress, talks to us about Noma's staff training, his daughters, reindeer moss, and more.

You know those books that you carry around everywhere, that are tattered and stained with cookie crumbs and coffee, that you take out every spare moment to read just one more line? Or those books that you page through to be somewhere else, to see the fun and creativity happening in another part of the world? Or the books that you stroke the pages of and read each recipe like it's a novel: excitedly, hungrily, and a little bit in awe?

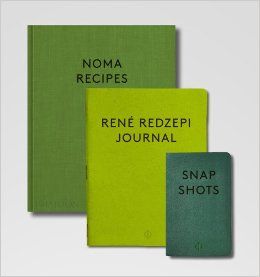

René Redzepi's A Work in Progress is all of those things.

Broken down into three separate books: Snapshots, Journal, and Noma Recipes, A Work in Progress is a vivid and honest look into the world of Noma, one of the most celebrated and talked-about restaurants in the world. In it, you'll find candid photos of the people and chefs behind the restaurant, René's own daily journal, and the recipes that he and his team have created.

Read on for René's thoughts on family, staff training, the life cycle of dishes, the annual MAD Symposium, and more.

What's the typical life cycle of a dish that's on the menu? How is it created, and how do you decide to take it off?

There are so many answers to this question. Most of the time, the dishes are determined by the seasonality of an ingredient. Let's say we want to work with wild raspberries: you really never know how long you'll have them around. Some years, it's three days. Other years, it's three weeks. So, naturally, that determines its lifespan on the menu.

Other times, we work for a long time on a concept that might be adaptable to several ingredients over the year. An example of this is the reindeer moss. It took us a while to figure out how to make it tasty, but as soon as we got to that point, and we knew we could get it all year round in large quantities, we ran with it.

An item like that we typically keep on until we, ourselves, get bored of it. Believe it or not, even moss, if you look at it long enough, will become to us as common as a leaf of parsley. What's interesting here is that we really love the process. That's what drives us -- the process of working to get somewhere. The result of the work comes in the form of a new plate of food, but at that point, it becomes about counting the days until we replace it.

You get cooks from all over the world. How do you train them to meet your standards? How do you set up a baseline for people with such different backgrounds?

It's actually quite simple: everybody that starts here, whether they are from Scandinavia or, say, Mexico, pretty much starts at the same level. Because people here in Scandivia historically have been so detached from their landscape -- understanding seasonality and what's around them, having a grasp of what's edible and inedible -- everybody more or less begins here at the same level. Most of the ingredients we play around with are as exotic to a Dane as they are to a Colombian.

We tend to choose potential staff members that have the greatest sense of curiosity, and not so much the ones boasting the most impressive résumés. We've found, over the years, that the people that are too set in their ways, too absolute, so to speak, in their approach to cooking, won't really fit in here.

You can invite any five people over to your house for dinner. Who would you invite, and what would you cook?

Assuming I can invite someone who isn't living, I would welcome the author Karen Blixen and make dinner for her and my two daughters, Arwen and Genta.

I would cook something out of Babette's Feast, and I would have my daughters be inspired by one of the most powerful women that I have ever read about. I'd ask Karen to look after my daughters, feed them, tell them stories. I would like to keep it a bit intimate for the girls. Too many people spoils the fun.

Tell us more about your Saturday Night Projects. In what ways have you seen your staff grow over the course of their time at Noma?

Saturday Night Projects started out as a venue for chefs to play around with their intuition and sharpen their sensibilities. It was supposed to be a place where we could fight against the more robotic aspects traditionally associated with our trade -- chefs following recipes only, disregarding their sensibilities, not realizing that recipes ultimately are just strong guidelines. In the end, it's the cook that stirs the pots and pans and creates the magic. A little squeeze of lemon juice, an extra pinch of salt, are small gestures, but they can have huge yields when cooking. Even if it's not written in the rules.

It has worked for us, the Saturday Night Projects. People have become more confident. They ask new questions. When it's their turn to cook a dish that they have been thinking about for weeks, for the whole staff, it's a daunting moment that really takes guts to jump into.

I've also discovered that Saturday Night Projects has become an opportunity for me to see where chefs are in their evolution. Typically, at first, the ideas are not so strong; the food that comes out can be a bit all over the place. With time, it changes. Give it a few years, and you might start seeing some masterpieces. Once that happens, that's also when I know they'll be leaving soon.

What do you see in the future of MAD? In what ways would you like it to grow, and how do you plan on getting it there?

The future of MAD, in terms of content, looks very bright, and we are ready for many years to come. The biggest challenge we have is staying independent. We don't want large-scale food companies to be a part of it, because that ultimately could compromise the spirit of the event. And frankly, we'd rather just say, "Hey, that's it, let's just stop," before it gets to that point.

We literally finish every MAD thinking, "That was our last one." Each year, our funding reserve starts at $0. We never know if we will get there. But the spirit of it will remain the same: it's a place for the industry to discuss the state of our trade and culture. It's a place to try to understand what's happening to our profession and how we'd like to see it evolve. We can't ask the same questions cooks did twenty years ago. It's a completely new time.

That's why I think MAD is relevant and necessary.

What is your end game? Where do you see yourself -- and the things you've created -- in ten, twenty, thirty years?

My end game...Well, I would like, at a minimum, four children, if I can persuade my wife. It would be my greatest accomplishment.

See what other Food52 readers are saying.