You know how some people are obsessed with stamp collections or fantasy football teams? Well, we're obsessed with cookbooks. (Surprise!) Here, we'll talk them.

Today: Lara Hamilton, owner of Seattle’s cookbook shop Book Larder, knows a thing or two about cookbooks (and cooking from them—her shop has a kitchen!). Here, cooking lessons learned from traveling the globe—without leaving the kitchen.

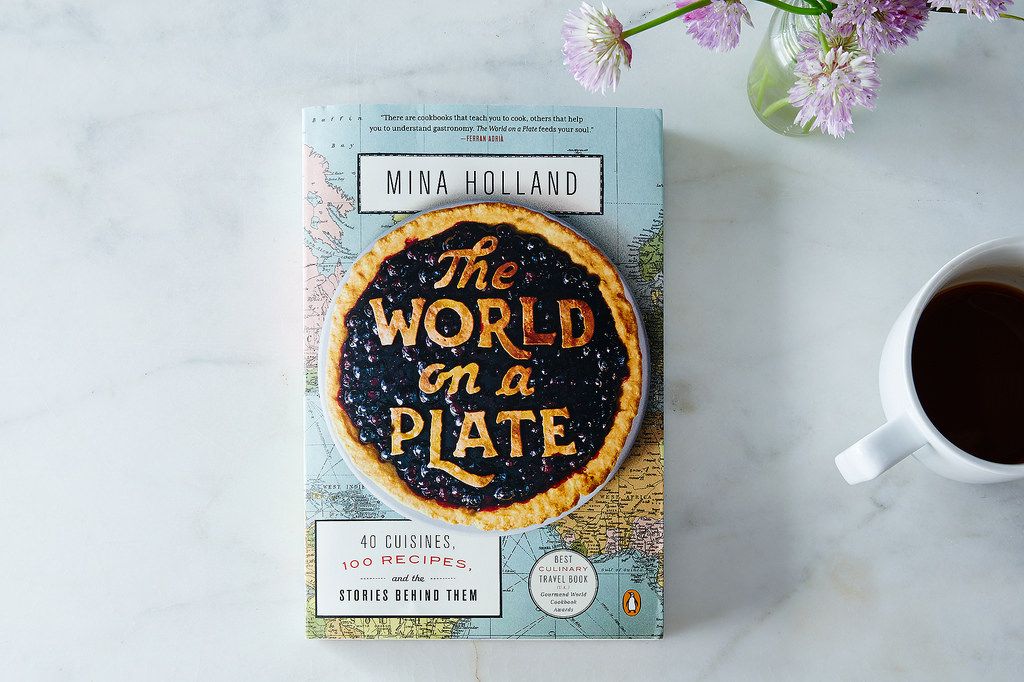

“When we eat, we travel” is the simple yet compelling premise of Mina Holland’s first book. Released in England as The Edible Atlas, the book explores 40 world cuisines, discusses what makes them distinctive, and offers a few key recipes from each—all while weaving in stories and dishes from (sometimes famous) cooks. Think of it as a global Genius Recipes, with more narrative. It’s a great beach read for food nerds like me, and an excellent companion for traveling the world from your kitchen. It covers so much culinary ground and has many lessons to offer, but a few parts of the journey stand out and are worth exploring further. Here are five things The World on a Plate will teach you:

1. Cooking isn’t everything.

Some scientists believe our ability to contain fire and cook our food was critical to human development, but I’ve always admired the brave ancestors who first ate all those raw berries and leaves (I mean, who first opened an oyster and thought “That looks good?”) Were they discovering a delicious meal or a quick way to die? As summer approaches, it bears remembering that thanks to those ancient culinary pioneers, we don’t have to heat up our kitchens in order to enjoy a great meal.

My family loved Holland’s Peruvian Ceviche, a classic blend of lime, white fish, chiles, garlic, and herbs topped with avocado and corn. She mentions that Andalusians make big jugs of gazpacho that they drink all summer. So the next time our Seattle temperatures get too high, I’ll be pairing these two dishes, getting into the kitchen in the morning when it’s still cool, and letting my fridge do the work.

2. You’re closer to a global meal than you think.

For all of the tremendous variety in this book, it’s clear that there are simple ingredients and techniques that unite what we all cook and eat. Core ingredients like onions, garlic, rice, and beans run through nearly every cuisine in the book. Holland handily summarizes the use of “sofrito” throughout the world, the combination of a few key ingredients that, when fried, are the basis of many dishes (think the classic French combination of onion, carrot, and celery). I was excited to see that I’m often just one or two ingredients away from exploring a cuisine I haven’t tried before.

So while I might normally turn chicken, chiles, garlic, onion, ginger, and spinach into a stir-fry, if I pick up some plantains and add tomatoes and shift the ingredient proportions a bit, I can instead make a West African hotpot and expand my family’s mealtime horizons.

More: The best ways to store and cut tomatoes.

3. We all like to get our funk on.

Fermentation is definitely a culinary trend right now, as both professional and home cooks are exploring new ways to add flavor (and healthy probiotics) to their meals. In our refrigerated Western homes, it’s easy to lose sight of the fact that this practice was born of necessity, as those brave ancestors I mentioned earlier sought to preserve foods through the seasons. From yogurt to pickles to kimchi and fish sauce, fermented foods add a salty, funky edge to so much of what we like to eat, and I was surprised to see just how many of these foods are considered signature dishes. Korean kimchi, German sauerkraut, and Scandinavian gravlax are just a few of the recipes featured in the book, and it makes sense: These are the foods that could be eaten year-round, and therefore earned their enduring place in each country’s culinary history. So everything old is truly new again.

4. We’ve influenced each other for centuries.

Modern globalization means we have access to a huge range of ingredients from around the world, either in shops or on the internet. It’s easy to think of “fusion” as a 20th century culinary term, but some countries’ iconic dishes were heavily influenced by other cultures centuries ago. Take the Peruvian ceviche mentioned earlier: Japanese settlers (or Nikkei as they are sometimes known) brought their experience of using raw fish.

Chiles are an integral part of so many world cuisines that I assumed they were native to places like India and China, but in fact they were brought from the “New World” (likely Mexico or Peru) by Columbus and spread along the spice route by the Portuguese only 500 years ago (and it took only a century for the people of Thailand to make them a ubiquitous part of their cuisine). And in a more obvious and recent example of influence, Britain’s love of Indian curry has virtually made it a national dish. But I was surprised to learn that we also have the Brits to thank for Japanese katsu curry—they inspired its creation some 100 years ago.

5) It’s impossible to sum up the world in 100 recipes, or to even get close.

Holland is a well-traveled writer, and the narrative’s strongest and most vivid points come from her personal stories: her year studying abroad in California, the time she spent living in and falling in love with Madrid, childhood visits to Thailand where her grandfather had retired. She acknowledges in the introduction that the book is an “entry point,” and I think she succeeds admirably in encouraging the reader to want more (and helpfully includes a comprehensive bibliography so you can dig more deeply where your interest leads you).

More: Pok Pok this way.

She also calls out the big themes throughout the book, with insightful graphics like a map of the spice route, a guide to how wine grapes have traveled, and a view of where those chiles from Peru and Mexico landed. As someone who spends a lot of time with cuisine-specific books, I appreciated stepping back and seeing the big picture. I liked realizing I could and should experiment with African cuisine beyond Morocco, so I am on the lookout for plantains and can’t wait to make my first hotpot. But maybe not today. It’s supposed to be 85° F—time to play Andalusian and blend up a jug of gazpacho.

Photos by James Ransom and Bobbi Lin

See what other Food52 readers are saying.