Join The Sandwich Universe co-hosts (and longtime BFFs) Molly Baz and Declan Bond as they dive deep into beloved, iconic sandwiches.

Listen NowPopular on Food52

15 Comments

healthyservesone

September 7, 2013

If you get a chance, have a look at Heston Blumenthal's Medieval Feast episode of Heston's Feasts. Lamprey anyone? Yes, it takes a molecular gastronomy chef to recreate these dishes!

sfmiller

July 21, 2013

Interesting piece. It's worth noting that the sort of medieval cuisine described here would have been eaten only by a small minority of the population--the privileged classes, who could afford to raise or buy meat and purchase spices (outlandishly expensive in those days) and retain cooks and domestic servants to prepare elaborate dishes (you can bet the cookbook author's teenaged wife wasn't prepping those eels herself!) The display and consumption of food was a key marker of social class.

A typical peasant or urban worker ate mostly grains (baked into bread, cooked into porridge, or brewed into ale) and legumes, sometimes supplemented with cheese or eggs; very little meat or fish, and vegetables only in season.

A typical peasant or urban worker ate mostly grains (baked into bread, cooked into porridge, or brewed into ale) and legumes, sometimes supplemented with cheese or eggs; very little meat or fish, and vegetables only in season.

Sophia H.

July 21, 2013

I agree, but I would also say that there are no low end cookbooks until Mrs. Beaton, and that was still middle class. Food for anyone under the wealthy and merchant classes are the only ones who would have been targeted, and it is not until after WWI that not having domestic help would have been an issue. The middle classes up until then almost always had some kind of domestic help. The idea of the nuclear family with the mom and female children were the only ones working on the domestic work is only since the mid 20th century. So, yes I guess it is a note, but it was just the way our society was, Instead of retail or service industries we had domestic help. Also you have to remember that the majority of even the wealthy classes were illiterate, so cooking was still a passed on and oral tradition.

I would venture to say most or our human culture that were record is not of the working classes, or urban workers. It is well know that fast food has been the main staple of the majority of humans living in large populations. Ancient Romans, Chinese, or as I said large dense populations did not have kitchens in the home, most food was bought prepared or brought to the home of the average family or worker, not prepared in the home. Even here in San Francisco's China Town, there are residents who had the food delivered prepared by local restaurants and then was consumed in the living quarters. and that was well into the 20th century.

I would venture to say most or our human culture that were record is not of the working classes, or urban workers. It is well know that fast food has been the main staple of the majority of humans living in large populations. Ancient Romans, Chinese, or as I said large dense populations did not have kitchens in the home, most food was bought prepared or brought to the home of the average family or worker, not prepared in the home. Even here in San Francisco's China Town, there are residents who had the food delivered prepared by local restaurants and then was consumed in the living quarters. and that was well into the 20th century.

wjd

July 19, 2013

fyi: i'm assuming you realize that turkey legs cdn't actually have constituted part of the european medieval diet, since they're native to the americas, and had to await european "explorers" to carry them back on their homebound trips; the first old-world turkey mention is from 1529.

Greenstuff

July 19, 2013

The potatoes too, of course, but I think she's referring to oddly American venues like this one http://www.medievaltimes.com/

Sarah J.

July 21, 2013

Right! Turkeys did not come to Europe until after the Columbian Exchange. I was referring to Renaissance Fairs, Medieval Times events, and food like this: http://thepioneerwoman.com/cooking/2011/10/caveman-pops-aka-roasted-turkey-legs/

Muddyfeet

July 19, 2013

Interesting article and comments. I like eating eel but not looking at them. So I for one, thank you for the picture of cute little glass eels. I wonder how turning the skin in as mentioned in the recipe benefited the dish. The fat I guess? Or maybe the tight skin held the filling together?

Sarah J.

July 19, 2013

Thanks, Muddyfeet! I am not certain how turning the eel inside out benefited the dish except that it probably cooked the "meat" of the eel more thoroughly (and made it possible to stew it in different flavored and spiced liquids, too).

I am definitely more a fan of those cute little glass eels than the ugly big guys. I chose the photo accordingly. I also did not want to scare off readers!

I am definitely more a fan of those cute little glass eels than the ugly big guys. I chose the photo accordingly. I also did not want to scare off readers!

Greenstuff

July 19, 2013

Actually, eel skin is much too tough to eat, it's more appropriately made into belts and wallets. I think if you look, the glossary for the book says that the reversed eel is skinned and deboned before being turned inside out, essentially butterflied. Interestingly the glossary also goes on to say that the reversed eel is cooked in red wine, a preparation that remains popular in Europe to this day. (Page 344, sarah, thanks to amazon preview.)

Greenstuff

July 19, 2013

And one more comment, just so you all know I'm obsessed in all directions. That is one great photograph by David Doubilet, one of the best-known photographers of marine animals of all time. The picture is of young eels at a stage when they are clear rather than pigmented. European and East Coast American eels are both born in the middle of the Atlantic, then migrate to one or the other coasts at this young age. They live in estuaries and upriver waters for many years before making the long swim back to spawn. The little "glass eels" in the photo would be far to small to turn inside out and stuff. Most states have outlawed fishing for them anyway.

Sarah J.

July 19, 2013

Thank you for your comments! I didn't want to scare off readers with a photograph of a full-blown eel, which is why I chose the cuter ones. I hadn't heard of David Doubilet before writing this post, but now I'm anxious to check out his other photographs!

Greenstuff

July 19, 2013

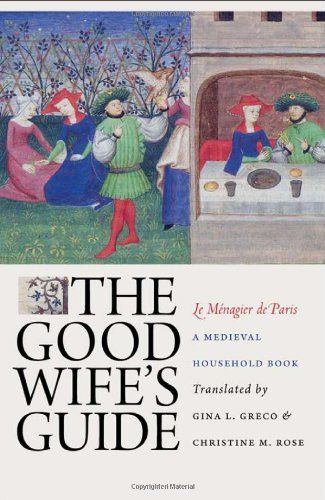

While I wait for The Good Wife's Guide to show up, I pulled the other book sarah jampel mentions, Paul Freedman's Food: The History of Taste, off my shelf. I had forgotten what a beautiful book it is, richly illustrated and packed with history. There's a chapter on the birth of Medieval Islamic cuisine as well as one on Europe in the Middle Ages. 2007, University of California Press, I highly recommend it.

Sophia H.

July 19, 2013

I have this book noted on one of my lists of antique cooks books, I have always been interested in ancient foods, and found the book and its history compelling. Though I though his wife was younger, I remember reading 13 not 15, which was not uncommon then. I used to frequent a site that is no longer up and wanted to try out all the all recipes, called foody.com, they had ancient roman recipes, up to Mrs, Beeton. There were a great many regency ones I wanted to try, I wish I had copied and saved them, since the site is not gone. :(

See what other Food52 readers are saying.