At Hartwood, the restaurant we run in Tulum, Mexico, our cooking isn’t complicated. That’s because our kitchen—humid, smoky, crowded, exposed to the elements—can’t pull off anything that calls for extreme precision or control.

But the food we produce is complex because we use what’s around us to build flavor. Every dish has a balance of sweet and spicy, fresh and dried, oil and acid. Some of our flavoring elements are very simple: honeys, salts, fresh and dried herbs, fresh and dried chiles. Some take more work. The pickles need time to sit, and the three oils we use—roasted chile oil, roasted garlic oil, and roasted onion oil—take some effort to prepare, but they’re essential to our cooking.

Here are some of the ingredients you’ll see filling our kitchen crates, lining our pantry shelves, and hanging from the rafters to dry. Our advice for finding the less familiar ones: almost every town now has a Mexican grocery store. Also, many of the fruits that grow in Mexico also grow in Asia, so if you can’t find them at a Whole Foods or Mexican market, check out your local Chinatown. Before you start ordering online, get to know your community.

Chile Árbol

Down in Mexico, even the dried chiles are a little moister and fresher than the ones you get in the States, which have been sitting for who knows how long (another reason why it’s really worth seeking out a Mexican market). The tiny medium-hot guy is a workhorse at Hartwood. We use the dried chile in many of our dishes.

More: A burger with a chile arból kick.

Prickly Pear

The fruit of certain types of opuntia cactus, this is also called cactus pear or, in Mexico, tuna roja, thanks to its vibrant color, which ranges from hot pink to purple when ripe. It has the grainy texture of an overripe pear and the flavor of an extremely mild quince paste.

More: 10 ways to use prickly pear.

Dragon Fruit

This vine-like plant grows pretty much anywhere it wants to: in trees, alongside buildings. The fruit is deep pink with soft thorns; inside, the speckled flesh dotted with black seeds looks like the upholstery on an 1980s sofa. It’s usually used for juice, but the soft, fibrous texture of the fruit is also good in salsas or ceviche.

More: How to prep dragon fruit.

Chayote

Part of the gourd family, this wrinkly pear-shaped vegetable (it’s also called vegetable pear) has the qualities of a firm cucumber combined with a melon. It adds a crispness and a refreshing bite to salads.

Nopales

With a unique flavor that is sometimes compared to green beans, nopales (or cactus paddles or pads) are delicious grilled. They are very high in vitamin C and calcium. When cleaning, be sure to cut away the needles with the grain, not against it, and trim away any rough patches.

More: Grill some nopales and stick them in a torta.

Avocado Leaf

The avocado leaf has a distinctive licoricey taste we love. We add whole dried leaves to roasts and soups, and we use crumbled dried leaves as seasoning. Often, we’ll add a pinch of crumbled dried leaves to give a dish a final dusting of flavor. It’s important to use young avocado leaves, like the ones we hang up in the kitchen to dry.

Hoja Santa

Literally “sacred leaf” and also known as Mexican pepper leaf, these large, heart-shaped leaves have a flavor reminiscent of eucalyptus, mint, tarragon, and black pepper. Locals use them to wrap fish, to flavor green moles, and to make a liquor called verdin. Also excellent in ceviches, marinades, and stocks.

More: Put Hoja Santa in your next chicken mole.

Pepitas

When you go to a market here, you see pepitas (pumpkin seeds) in all stages—fresh in the shell, fresh and shelled, dried in the shell, dried and shelled, and dried, shelled, and ground into powder. Toasted pepitas add an earthy note to a sauce or a dressing—the key is to use just a little so the effect is subtle. They also make a dramatic garnish when crushed. Just like the Maya, we use pepitas nonstop.

More: Top this posole with pepitas.

Honey

Thanks to the incredible variety of exotic fruits and flowers here, Yucatán honey is unlike any other we’ve tasted. We use rich mamey honey to finish dishes and a light “common” honey in braises. (Unlike agave, which blends with the heat of chiles, honey balances it.) Buy the best honey you can find and keep in mind that the darker the color, the more intense the flavor.

Pickles

The Spanish word for pickles is encruditos, but in our kitchen, they’re simple called los pickles. We use them in almost every dish. Pickles provide the little bursts of flavor that clean your palate, provoke your senses, and prepare you for another bite. Two of my favorites are the eggs we pickle in Jamaica (hibiscus) flower and our grilled and pickled pineapple.

Flavored Oils

Roasted chile, garlic, and onion oil might seem pungent, but they’re actually quite subtle. The create flavor in every dish they touch, both as cooking and finishing oil for pretty much everything we serve. We’ll use an oil to season a piece of meat before it goes on the grill, then drizzle on a little more just before we send out a dish. For our roasted chile oil, we use mild cascabel chiles, which give it a pleasantly toasty, smoky flavor.

Makes 1 liter

24 dried cascabel chilies

1 red onion, quartered

3 thyme sprigs

3 oregano sprigs

3 bay leaves

1 one-liter bottle olive oil

See the full recipe (and save and print it) here.

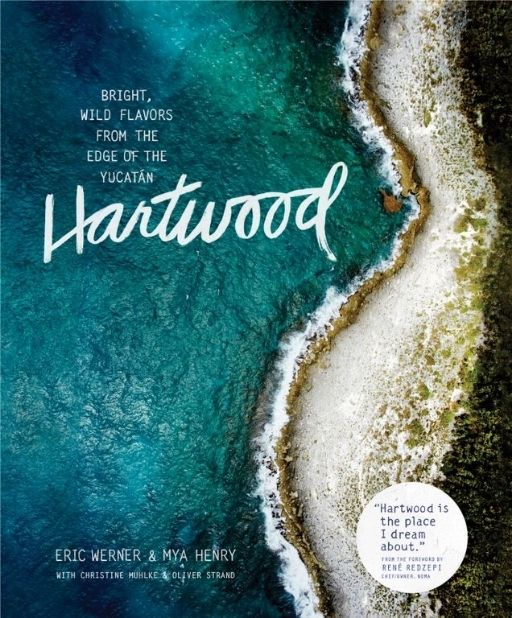

Excerpted from Hartwood by Eric Werner and Mya Henry (Artisan Books). Copyright © 2015. Chef Eric Werner began his culinary career at the Culinary Institute of America and honed his pastry skills at Payard in New York City. Together with Mya Henry he owns and operates Hartwood in Tulum, Mexico.

Photographs by Gentl & Hyers and James Ransom.

See what other Food52 readers are saying.