This is the first in a 3-part series on food science from the Modernist Cuisine team. Stay tuned: On October 8th, we'll be selling Modernist Cuisine at Home at an exclusive discount in the FOOD52 Shop, and giving away a copy too!

Today: Learn heat transfer's tricky ways (and stop burning so much toast).

It’s Getting Hot in the Kitchen

By Nathan Myhrvold and Judy T. Oldfield

Heat is the fundamental transformative force in almost all cooking, yet it works in counterintuitive ways — unless you know a bit about the basic physics of heat transfer. In the kitchen, heat moves around in three main ways: by conduction, by convection, and by radiation. Most cooking techniques involve more than one form at once, but let’s take them one at a time.

Conduction

When you put a pan on a hot stove, the heat moves from the cooktop through the solid bottom of the pan and into the food that contacts it. This is conduction: fast-moving (in other words, hot) molecules in the flame or heating element bump into molecules in the pan and impart some of their energy. Those molecules then zip around in every direction to jostle their neighbors, and so on. The heat spreads, both sideways and upward.

How fast the heat spreads depends a lot on the material: it moves 5,000 to 10,000 times faster inside a metal pan than it does inside a steak, for example, and some cuts of meat heat more quickly than others. But the rate of heating also depends greatly on distance, and this is the source of many cooking mistakes. Many cooks expect a steak that is two inches thick to take twice as long to cook as a steak that is just one inch thick. Logical as that may seem, it is wrong. For steaks and other water-heavy foods, each time you double the thickness, the cooking time roughly quadruples.

When you’re buying new pans, think about how they will conduct heat. Yes, heat moves through copper a bit faster than it does through aluminum, so all else being equal, a copper pan will get hot faster. But if even cooking is what you’re after, the thickness of the pan is the bigger factor. In a thin pan, the distance from flame to food is so short that hot spots are inevitable. Thicker pans give the heat time to spread sideways on its way up, so the food experiences less various in temperature across the pan.

Practice the art of conduction with one of our favorite steak recipes: The Cowboy Rubbed Ribeye.

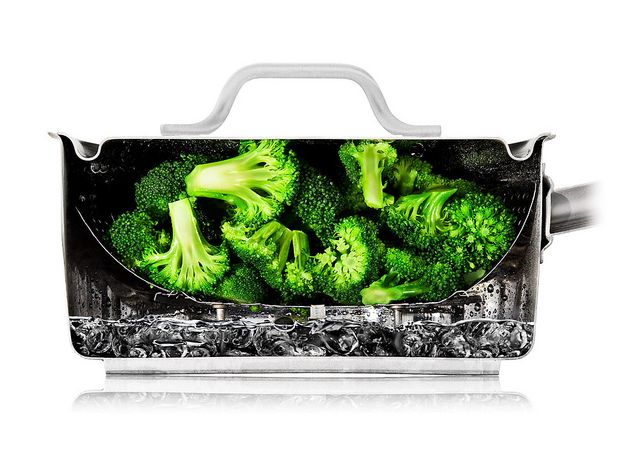

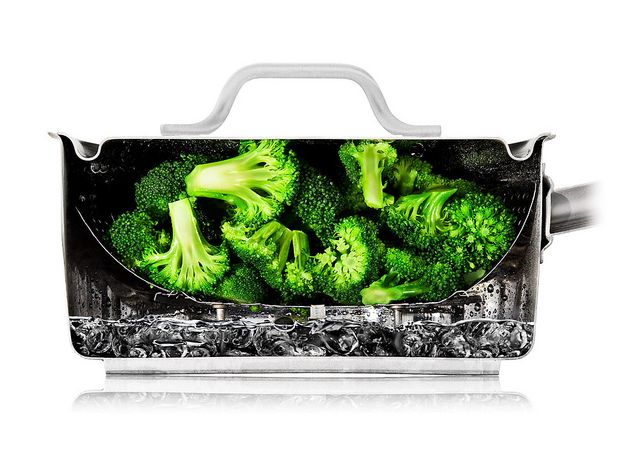

Convection

When you steam broccoli or boil pasta, you’re cooking by convection. The molecules in water, steam, and other liquids and gasses don’t have to collide with their neighboring molecules in order to transmit their energy. They can simply change their position — and take their heat with them. That flexibility can accelerate cooking enormously, and you can help it out by making sure the fluid has room to move (don’t overcrowd your pasta!) or by stirring it directly.

Just how much the currents speed things up is a tricky question, because you have to account for the density and viscosity of the fluid, as well as the velocity at which it is flowing. Fortunately, there is a single number, called the heat transfer coefficient, that summarizes the effects of these factors. It reveals that sous vide water baths and forced convection ovens heat food up to ten times as fast as the natural air convection that happens inside a conventional oven. That is why you can extend your hand safely for a moment into an oven filled with 350 °F air, but will get a nasty burn if you hold your hand for long over a steaming pot of boiling water.

Convection heating has its shares of subtleties. Steam transfers energy more efficiently than boiling water, so like many chefs, we assumed that steaming vegetables is always faster than boiling them. But when we put that idea to the test, our experiments showed that steaming is actually slightly slower for most vegetables (although we still prefer it, for reasons of taste and nutrition). As the steam condenses on the surface of the food, it releases a great deal of heat — but the resulting droplets merge and cool to form a thin layer of water that partially insulates the vegetable from the steam.

Harness the power of steam (and convection) in your scrambled eggs.

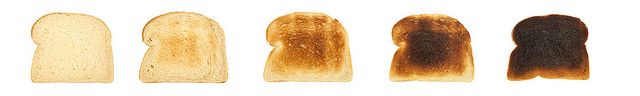

Radiant Heat

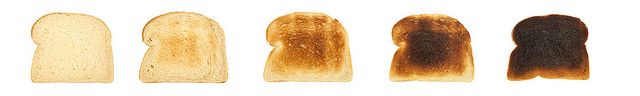

The radiation you cook with is not the nuclear kind; it’s some form of light (mostly invisible to the human eye). Microwaves, broilers, grills, toasters, and glowing coals all pump out energy through radiant heat. But, being light, the rays can reflect off the food. So how fast food grills, broils, or roasts depends in part on its color. It’s like walking barefoot on a sunny summer’s day. A concrete sidewalk may be quite comfortable on your feet, but step onto blacktop and you start hopping!

Similarly, shiny fish scales and white floured dough reflect heat rays really well, so they absorb heat slowly at first. But as food browns, the faster it absorbs heat, and cooking accelerates dramatically.

You may see this when you toast a piece of white bread. After two minutes it pops up too light for your liking, so you press the lever and toast it again.

By the time you’ve poured your orange juice and the toast pops back up again, your toast is charred. What happened? As soon as the bread started to brown, its reflectivity began to plummet, and heat absorption skyrocketed. Bread goes from brown to burnt in a tenth the time it takes it to go from white to brown.

Who us -- burn toast? Never.

So next time you grill fish, boil pasta, or broil a steak, think about heat transfer and how you will control it. With that fundamental handled, you’ll find it easier to innovate and express your artistic ideas through your cooking.

Photos: Book - Chris Hoover; Steak - Nathan Myhrvold; All others - Ryan Matthew Smith / Modernist Cuisine, LLC

See what other Food52 readers are saying.