When Food52 invited Canal House to be judges for the 2012 Piglet Tournament of Cookbooks, we were honored indeed. Our debut volume of Canal House Cooking (N° 1, Summer) was a nominee two years ago and we were thrilled to be part of the exciting ride. Now we have the difficult task of choosing between two very fine, appealing cookbooks. Oh dear God, why did we say yes? But yes we said, so here we go...

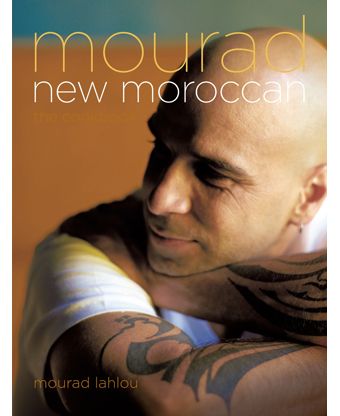

Mourad: New Moroccan by Mourad Lahlou has a striking cover: It's an intimate photograph of the chef himself — completely bald, pierced like mean Mr. Clean, his arms decked out with fat black tats — an intense-looking guy in golden light, a relaxed tell-me-a-story pose, with a wistful expression on his face. It's an Artisan book, so you know it's beautifully designed. The evocative images, by photographer-to-the-star-chefs extraordinaire Deborah Jones, capture the colorful, earthy richness of Morocco, Lahlou's homeland, and the hip, sophisticated food from his San Francisco restaurant — juxtaposing these contradictory elements gracefully throughout the book.

Lahlou grows up in Marrakech, raised by his mother and her extended family. As a young lad he accompanied his beloved grandfather on his daily shopping rounds to the markets, bringing home the ingredients for the women to cook that day. Though he never cooked as a kid, he was surrounded by women — mother, grandmother, aunts, nanny, and housekeepers — who did. All of them preparing the exquisite flavors, aromas, and textures typical of Moroccan home cooking. After high school, Lahlou got top scores on the baccalaureate exams and was on his way to France to continue his studies but made a daring, last-minute decision to head to San Francisco instead, where his older brother was living. He waited tables at Mamounia, the Moroccan restaurant around the corner from his apartment, while attending San Francisco State University where he graduated with a BA in economics. Eventually, Lahlou got a master's degree and began applying for doctoral programs. Homesick for the flavors he grew up with and unable to find them even at Mamounia, Lahlou began experimenting in his tiny apartment kitchen. After a few frustrating months, he connected with his childhood memories and began to recreate the flavors and dishes of his mother and the women who raised him.

Eventually, his brother (a restaurant manager who dreamed of having his own place) convinced Lahlou to ditch the academic path and go in with him on a restaurant deal too good to pass up. They opened Kasbah in Marin County, but five years later they closed it and opened Aziza, in honor of their mother, in San Francisco. Lahlou eventually allowed his pursuit of authentic Moroccan cuisine to meld into and reflect his northern California surroundings, which by now had become his home. His "culinary daydreaming" reflects both sides.

Here is Mourad's story and his cookbook, full of recipes and his philosophy of flavor.

Oddly, the first recipe we choose to make is Fig Leaf Ice Cream. Why? Well, the title is appealing and hints at the promise of a pretty honeysucklelike sweetness. And the photograph pulls us in. It's sheer. Delicate. And the pale green ice cream looks so refreshing. We don't live in fig tree country, yet we grew two big plants on our balcony at Canal House, so we want to make it. We harvest the last of the leaves before the plants go dormant for the winter, make the ice cream, and have our first flavor from Mourad. Green. The sticky, milky juice from the veins of the fig leaves imparts a mild sweet flavor, grassy, like Japanese green tea ice cream. Neither of us picks up any fig flavor. The ice cream is good, but not our favorite.

Preserved lemons. We're never without. We make big jars of them at Canal House and there's almost nothing we don't use them in. The method is simple: Salt-packed lemons in turn get tightly packed into a jar, then covered with fresh lemon juice. The lemons are left to soften and cure. About a month later they're ready, offering up their rich, deeply salty, sour selves. Mourad devotes a ten-page chapter to preserved lemons, and takes three pages to explain the method for making them. Fair enough. He says they are "Morocco's greatest contribution to the world." And for the uninitiated, Mourad gives heartfelt reasoning for making them. After all, "it's incredibly easy, and the payoff is huge". Then he walks the apprehensive reader/cook through the experience of tasting their first preserved lemon. It's clear Mourad is passionate about the intoxicating flavors of his culture, so for the neophyte, he's an encouraging guide. And if you came away with only one recipe from his cookbook, learning to make and use preserved lemons would be well worth the book's price.

We couldn't resist making Rghaif with Three Fillings. The accompanying photograph shows a soft yeasty dough folded and wrapped around a savory filling, then flattened, beautifully browned, and sliced into triangles. We want to eat them again as we write this. We chose to make the most traditional sounding filling of the three: Caramelized Onion with Spice and Currant. The dough is that marvelous kind that feels so good in your hands: soft and supple, milky sweet, like a baby's bottom, but one that was just rubbed with melted butter. The fragrance that fills the kitchen when the cinnamon, nutmeg, clove, and saffron meet the caramelizing onions in the skillet is heady and instantly transports us. There's no mistaking which culture this food comes from. Everything goes well with both the filling and the dough until the last step before cooking the pastries. We must have not worked carefully enough (as the recipe instructs) because the dough did tear and expose the filling. Maybe the dough became too thin earlier in the recipe when we were instructed to pat each dough ball into a 10- to 12-inch circle; some patches of those discs became tissue-thin. Ultimately, those patches lost their ability to retain the filling, and once the pastries were cooking in the skillet, some filling oozed out and burned in the pan, marring the picture-perfect packages of beautifully browned pastries. Next time we'll be more careful.

Harira, the nourishing Moroccan soup traditionally eaten during the month of Ramadan, is a favorite of ours and we were intrigued by Mourad's fiddled with, deconstructed version. He garnishes his tomatoey lentil soup with a diced celery salad, and instead of the customary plate of dates served on the side, Mourad rolls the dates into balls and adds them as another garnish. Cooking our way through the long, difficult-to-follow recipe for a tomato-lentil soup (not a complicated bisteeya of Fez with homemade warka) made us feel less than a chef and not even such good home cooks. We wonder how people follow such lengthy recipes without losing their place, their concentration, their interest. By the end, we had five quarts of a pretty good soup that didn't really sing. The best part were those cute little date balls in a pool of good olive oil, and we've since made them with fresh Medjool dates, adding them to braised lamb, beef, and chicken dishes.

We're egg-o-philes and the last recipe we tested from Mourad was the shakshouka-like dish of Kefta Tagine Custardy Egg Yolks. We were eager to sink our teeth into something delicious that wasn't chefy or tricked-out. The tomato sauce was full-flavored, sweetened with carrot juice, and seasoned with preserved lemons, paprika, cumin, and one-sixteenth teaspoon (we don't own a measuring spoon that tiny and our computer formatting doesn't contain this fraction) of cayenne, 1½ teaspoons of chopped parsley, and 1½ teaspoons of cilantro. Why the uber-precise measurements for seasoning 4 cups of tomato sauce? We couldn't figure it out, but it was tasty. For the kefta, we turned to another page in a different section of the book, following part of another recipe, making just the ground beef and lamb meatballs that get simmered in the tomato sauce. Then the eggs, the best part, freed of their whites, they simmer in the tomato sauce until just warmed through. And they're just as described: custardy. And delicious.

Although Mourad is chatty, friendly, passionate, and encouraging, we never really get a sense of Mourad's voice — this interesting man from Morocco, his way of speaking and phrasing — from his writing. What we do get is a completely professional cookbook, beautifully photographed and designed, the recipes perfectly correct in their style and in today's standard recipe-eze. Sadly, his voice feels ghosted.

The Restaurant Joe Beef is a mecca for Montreal food lovers. Frédéric Morin and David McMillan opened it in 2005 in the historic but fringe neighborhood of Little Burgundy. Morin attended Quebec's L'École Hôtelière des Laurentides, where he learned his way around classic French cuisine. He worked at the finest restaurants in Quebec and Montreal. McMillan, a painter, was also in the food scene and earned his stripes by living in Burgundy and by learning la cuisine bourgeoise, French home-style cooking, from the Montreal restaurant legend, Nicolas Joungleux (who died at age 33 in 2000).

So they both knew their way around a restaurant kitchen when they decided to join forces and open a restaurant. They named it after a legendary nineteenth-century tavern owner, Charles McKiernan, known as "Joe Beef". His establishment was described as "a museum, a saw mill and gin mill jumbled together...a place for the working class, laborers, longshoremen...a wild place, with a menagerie of monkeys...." So it was clear from the start that the new Joe Beef was going to be something original, with twirled-up and twisted versions of classic French food and drink from the mischievous minds of Morin and McMillan.

It's the classic story. They rolled up their sleeves, asked for help from their friends, and, as they say, "The restaurant came together with love, about twenty packs of wainscoting, and unlimited generosity and interest from friends." They wanted it to be different from the places where they'd worked before. They wanted it to be fun and interesting, with art on the walls, great food, good music, and delicious wines, someplace that they would like to hang out. They built the tables, found old tavern chairs, and filled the walls with friends' paintings, vintage 1970s photographs, a bison's head, and old signs. As Joe Beef came together, it felt like it had always been there.

We can understand having a business plan of "If you build it they will come." We did the same thing when we started Canal House — create your own world, populate it with like-minded folks, and tune out the statistics of failure and the world of "no". To other business people, it must be like watching someone jump out of a plane or off the top of Half Dome, rejoicing in their freefall, having the time of their lives. What looks like certain death to some is being fully alive to others. So Morin and McMillan were fearless (or perhaps it just seemed to them like the next thing to do), they opened their small restaurant and cooked the food that they adore, Paul Bocusian cuisine du marché Lyonaise, and it was quite perfect since they are adjacent to the Atwater Market, filled with butcher shops, fishmongers, farmers selling fruits and vegetables, and cheese makers.

Today it seems that everything is a paler version of something that came before, but every once in a while something original shows up — a clear, personal vision that is someone's unique take on things. That's why everyone wants to eat and hang at Joe Beef: it is really cool (and maybe some of that coolness will rub off).

We've never had the pleasure of visiting the said establishment so we were very happy last fall when Ten Speed Press published The Art of Living According to Joe Beef: A Cookbook of Sorts. Even if you never make one recipe from this book, it's still worth buying, and it's a wonderful read. It is really their manifesto, how to live and eat like you mean it. Meredith Erickson, a writer and former Joe Beef employee, spins the tale. Her writing catches the vibe. She knows the culture from the inside out and gives us an insider's view. This book is a free pass into the club, and the fun that Morin and McMillan serve up.

The book design is beautiful and clear, organizing the lovely cacophony of images, historical sidebars, cooking tips, tales, and recipes. The photographs of the restaurant, its garden, and its cast of characters are lovely and real, and as we read the book, we spent lots of time looking at them and seeing how quietly they tell the outrageous story. Photographer Jennifer May captures it all. She understands the sensuality and beauty of food and never flinches as she shoots some pretty over-the-top dishes just as they come to her.

But what about the recipes? We were excited. We love this food, so a chance to don our aprons, pull back our hair, and try our hand at some big Burgundian dishes whetted our appetites. We like voice in recipes. When they describe rolling and tying pork skin: "Roll the skin up tightly and tie it around and around with butcher's twine, like you would a cheap sleeping bag for a college trip to Camp Crystal Lake. Set aside." Very funny and we knew just what they meant.

We eased in with Kale for a Hangover. A classic preparation, first blanching the kale, then cooking it in rendered bacon fat along with lardons, garlic, onion, half a cup of white wine, and finished with a pat of unsalted butter and a squeeze of lemon juice. It was delicious, pretty much how we cook our kale, but we never bother to blanch it first and don't add white wine. No need to wait for a hangover! But it didn't feel like a true test, it was a mite too easy and familiar to us.

Now we stepped it up, we'd give Pork Fish Sticks a whirl. The full-bleed picture sucked us in and told the story — shredded pork shaped into fish-stick shapes, breaded, then deep-fried to a golden crispness. Seemed like it might be a Joe Beef signature dish, an amusing, slightly irreverent, culturally referential title, belying the involved preparation.

While a spice-rubbed five-pound pork shoulder slowly roasted for nine hours, we killed a few minutes making the BBQ Sauce, which involves a bottle of Coca Cola, ketchup, cider vinegar, molasses, sriracha sauce, and instant coffee. But the sauce was not our favorite; the instant coffee and molasses made it strangely bitter. Maybe it's a Canadian thing.

On day two we shredded the pork, then mixed it with the BBQ Sauce and gelatin (had to use Knox powdered gelatine since sheets just aren't available to the home cook here). Then we patted the mixture onto baking sheets and put it into the fridge to set up. (It did take us a while to clear room for two baking sheets in our already full fridge. Wish we had a restaurant walk-in.) It chilled there for a few days. Since there were only two of us, 5 pounds of meat sounded daunting, even to our healthy appetites. Luckily, two days later, six people showed up around cocktail time. So while they knocked back some vino we cut the pork into rectangles, dipped them in flour, egg wash, and panko, and fried them into crispy little sticks. Everyone loved them and we did too, even though it took three days to make them. Next time I think we'll just serve the delicious roasted pork shoulder.

Now we were rolling, so we took on Pied-Paquets with Sauce Charcutière. The picture shows fat little packets of the meat pulled from braised pigs' feet and lambs' necks, mixed with spinach and herbs, all wrapped up in caul fat, and served with an old-fashioned French sauce of beef stock twirled up with gherkins, mustard, and shallots. This would be a much worthier test.

But we live in the hinterlands, so after a search we eventually had to special order trotters and necks from our butcher. It took a few days, which almost killed the buzz. When the pigs' feet and lambs' necks were snuggled in a pot along with their friends the mirepoix and the aromatics in a nice warm oven, we thought we'd make the sauce. Screeching halt. We hadn't noticed that we had to make the beef stock. Okay, our mistake, off we went in search of beef shin. We seared the shin and all the vegetables and aromatics until everything was golden brown, then into a big pot with water and red wine. Four hours later we had a pot of rich, flavorful ambrosia. This will be the way we make our beef stock from now on. While it cooked we pulled the meat from the lamb bones and removed all the gnarly bits from the pigs' feet (the recipe didn't mention what to do about the skin and now we can't remember if we used it or not.) We strained the cooking liquid and drank what was left of the bottle of wine that we used in the stock. But the day was shot, so we strained the stock and left it out on the fire escape to cool overnight. Tomorrow we would peel off the layer of cold fat and we'd be ready to make our paquets.

Day two, not so fast, no caul fat in our neck of the woods. We know we should have assembled everything before we started but we are just like everyone else. So we searched online and find that we'll have to order a minimum of twenty pounds, but we only need eight ounces. Now we could have gone Gaga style and made caul dresses to wear at the Piglet, but no, instead we drove the sixty-five miles into NYC to Faicco Pork Store on Bleecker Street where they sell caul fat every day, as much or as little as you want. We love New York City. We ate lunch at Gramercy Tavern. This recipe was beginning to cost us plenty.

Day three, we try to explain to our editor why we need an extension on our own book deadline. We add cooked spinach and herbs to the meat, then make caul-wrapped paquets that we heat in the oven until they are nice and brown. We finish the Sauce Charcutière. We each taste a spoonful. It is just wonderful, tastes like Burgundy, and takes us right back to À Ma Vigne, a tiny bouchon in Lyon. With layers of rich flavor, bright notes of gherkin and capers, there's nothing faint-hearted about this. It would be good on, over, or under anything.

We set the table, call in our neighbor, make an escarole salad, open a bottle of red, and spend most of the afternoon at the table. With food like this, why not? We caught the Joe Beef fever.

The truth is we don't really like the premise of choosing one book over the other. They are both wonderful. We wanted to love Mourad, but the recipes we tried didn't seem to live up to his reputation and the rave restaurant reviews he's received over the years. While the Joe Beef recipes were long and involved, in the end they were worth the effort. The food was great.

So choose we must, and Joe Beef wins the day.

The Piglet / 2012 / Semifinal Round, 2012

The Art of Living According to Joe Beef

David McMillan, Frederic Morin, & Meredith Erickson

Judged by: Christopher Hirsheimer & Melissa Hamilton

Christopher Hirsheimer is an award-winning photographer and the co-founder of Canal House, whose facets include a publishing venture, culinary and design studio, and an annual series of three seasonal cookbooks titled Canal House Cooking. Prior to starting Canal House in 2007 in Lambertville, NJ, Hirsheimer was the executive editor of Saveur, which she co-founded in 1994, and the food and design editor of Metropolitan Home. She co-wrote the award-winning Saveur Cooks series and The San Francisco Ferry Plaza Farmers' Market Cookbook (Chronicle, 2006). Her photographs have appeared in more than fifty cookbooks for such notables as Colman Andrews, Lidia Bastianich, Mario Batali, Julia Child, Jacques Pépin, David Tanis, and Alice Waters, and numerous magazines, including Bon Appétit, Food & Wine, InStyle, and Town & Country.

Melissa Hamilton is a renowned food stylist and the co-founder of Canal House. She previously worked at Saveur, which she joined in 1998 as the test kitchen director, and was its food editor for many years. Hamilton also worked in the kitchens of Martha Stewart Living and Cook's Illustrated, and was the co-founder and first executive chef of Hamilton's Grill Room in Lambertville, NJ. She has developed and tested recipes and styled food for both magazines and cookbooks, including those by acclaimed chefs and cookbook authors Colman Andrews, Lidia Bastianich, John Besh, Jonathan Waxman, David Tanis, and Alice Waters. She and Hirsheimer currently work on Canal House Cooking, for which they do all of the writing, recipes, photography, design, and production. Thousands of devotées check in daily to their blog Canal House Cooks Lunch to see what Melissa and Christopher have cooked up for lunch in their pretty kitchen studio. Their forthcoming book, Canal House Cooks Every Day (Andrews McMeel), inspired by their daily offering, will be published later this fall.

15 Comments