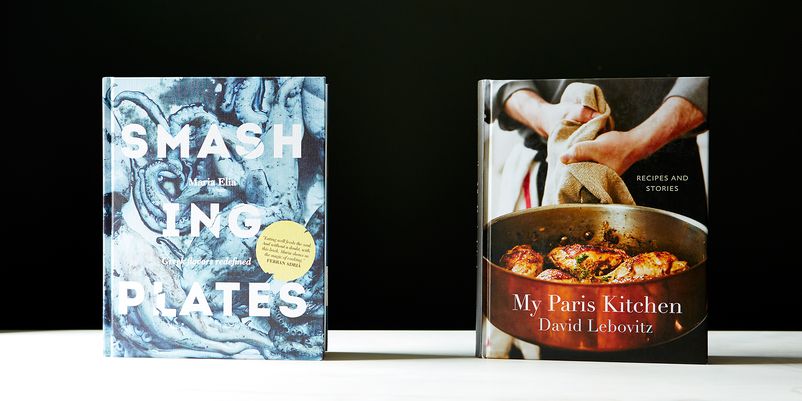

When I received my copies of Maria Elia's Greek-inspired cookbook, Smashing Plates, and David Lebovitz's largely French cookbook, My Paris Kitchen, they both looked so intriguing, I had no idea which one to start with. Luckily, Brendan, my willing accomplice and sous-chef in this project, and I had just been given a frozen leg of lamb by a neighbor, so we let the lamb decide.

The lamb chose Greek: It wanted, in fact, to be slathered in fresh herbs and spices, lemon, and olive oil, wrapped in parchment paper, and slow-roasted for four hours until it melted tenderly off the bone. I know I would have felt exactly the same way if I were a leg of lamb. So I started with Smashing Plates.

Not literally, of course. The plates stayed in the cupboard. But oddly, the title is referred to only obliquely in the introduction. Evidently, Maria -- I found myself referring to the cookbook authors as Maria and David as I cooked my way through their books, because they both started to feel like friends -- assumed that it’s common knowledge that this is a feature of traditional Greek weddings. Am I the only one who didn’t know that?

The book’s title also refers to the fact that the recipes are Maria’s modern twists on classic Greek recipes. She reminisces in the introduction about two dishes -- one with pork, one with peas -- her father, a Greek chef, used to make when she was little. I instantly decided to make both, but it’s just a tease -- she doesn’t give us the recipes. The book was compiled during the course of a summer when she went to her father’s village in Cyprus, watched people cook, and then put her own spin on the food she’d found; she doesn’t speak Greek, so she learned by watching and doing.

Smashing Plates is a modern, easy-to-use cookbook. The little anecdotes alongside the recipes are energetic and breezy, full of suggestions for variations of ingredients. However, they’re disconcertingly peppered with exclamation points, and they also occasionally become repetitive as she reintroduces people we’ve already met in the recipe prior. Overall, the book feels a bit rushed, and I found myself wishing that Maria had taken more care and time with it, slowed down a little.

But these are quibbles. This is a cookbook that you can easily live with for a week, as I did, combining and recombining dishes, using up all the bunches of fresh mint, oregano, parsley, and thyme you bought with the Greek yogurt, tahini, and feta. I made Sardine Keftedes, which were delicious and very light, almost like falafel, with rich, luscious pea hummus (substituted for fava beans, as Maria suggested; shopping at the local Hannaford in the wilds of New Hampshire in the dead of winter was a challenge) and perfect tzatziki. The next night, I made the gigantes plaki. I had to use cheap canned butter beans, rinsed and drained, instead of dried authentic Greek plaki, but no matter: This recipe for a simple bean stew is nothing short of sublime. I added the vinegar, as Maria suggested (when she suggests vinegar, use it). The next morning, going to the next recipe, we ate the leftovers on toast with feta, mint, and cherry tomatoes. I pawed through the cookbook as I ate this amazing breakfast: What next?

Next up was that leg of lamb, which had finally thawed in the refrigerator. Slow-roasted in parchment paper, subtly infused with cinnamon, cumin, dill, lemon, and oregano, it was luscious. We feasted on it for two nights with pea hummus, tzatziki, and tahini sauce. Maria suggests serving it with roast potatoes with lemon, but, as with her father’s tantalizing dishes, provides no recipe, so we improvised our own. They were perfect with the lamb, but a recipe would have been nice.

The next night, and again the next, I used the leftover meat in her equally excellent recipe for pulled lamb burgers with slow-roasted onions and more herbs and spices (and vinegar). All was not so delightful, however, with the two side dishes I made to go alongside: The Celeriac Purée was disappointingly bland and insipid, and the Lemon Parsley Salad that was “inspired by a cooking show I once watched on television in Tuscany” was weird and nearly inedible.

However, on the whole, I loved cooking from Smashing Plates. By the end of the week, the frigid White Mountains were balmy with Aegean breezes. The inside of my mouth felt alive and awake with piquant herbs and fresh ingredients, and my stomach was happy with all of this light, satisfying food that never made me feel overfull. (I had lost a few pounds, too, proving, perhaps, that the Mediterranean diet really does work, even when you’re not trying to lose weight.) Fresh oregano was a revelation: It’s nothing like dried. The food’s textures and tastes were varied, subtle, and cohesive, not forced, but respectful of a millennia-long marriage of these combinations. It’s a great cookbook for a multi-day house party, because everything’s meant to be eaten with everything else, and shared.

And then I took my stomach north and inland to join David Lebovitz in his kitchen in Paris, where he’s been living and cooking for a decade. (Maybe now is the time to confess that I am evidently the only home cook who had never heard of David Lebovitz; everyone else is apparently already his fan. But now I’ve come out from the rock I’ve been living under and joined the rest of the world.)

Like Smashing Plates, My Paris Kitchen is a cookbook to settle into and live with for days on end; again, I found myself with bunches of fresh herbs to use up, and again, I found myself pawing through the cookbook as I ate one meal, already planning the next. I also found myself reading the lovely, well-written introduction and essays at leisure, as all good food writing should be read. David hasn’t just written a cookbook; he’s created a world and invited us in to experience it as he does.

Unlike Greek food, French food is not light. Brendan and I dove, with resolute and willing decadence, into a rich bath of butter, eggs, cheese, and mayonnaise. David’s recipe for oven-fried frites replicates the ones served at our corner bistro, only they’re better because they’re homemade. I made the Salted Olive Crisps with Artichoke Tapenade with Rosemary Oil and was transformed instantly into an expert hors d’oeuvriste, a term I invented on the spot for how I felt. And oh, the buttery, savory, expertly French-tasting Baked Eggs with Kale and Smoked Salmon. I made them two mornings in a row, and I would make them every day for the rest of my life, if I were willing to gain ten pounds a month.

I kept going, and each successive recipe was as swoon- and drool-worthy as the last: Mustard chicken. Crab, fennel, and blood orange salad. Lentil salad with goat cheese and walnuts. Herb omelet. Raw vegetable slaw. (However, the recipe calls for two tablespoons of minced garlic: I love garlic, but maybe he meant teaspoons.) His celeriac purée kicked the ass of Maria’s; he advocates cooking the celeriac with a bay leaf in milk and chicken stock instead of plain water, and that makes all the difference. The leftover broth makes a wonderful soup, too.

Under David’s tutelage, I made my first mayonnaise. I made my first-ever pissaladière, that delectable French pizza of sweet caramelized onion and salty olives and anchovies on a crisp, thin crust. I couldn’t stop: I made the buckwheat crêpes slathered with seaweed butter and rolled up and fried in more butter, and they were so fantastically good we ate the entire batch in ten minutes and wanted more, our chins dripping with butter. But we moved happily on to Leeks with Mustard-Bacon Vinaigrette…

Then came the disappointment. The caramel pork ribs came out coated in a sticky sauce so sweet they were like candy, with tough, almost-burned meat. This caused me to reread David’s mini-essay about the French attitude toward cooking au pif, or by the nose: “Recipes are guidelines, starting points for cooks to diverge from. Take them in your own personal direction.” And so we did: The next night, we stuck the leftover ribs back into the oven for another hour at a lower temperature, and when they came out, we slathered them with Sriracha -- they were more tender and spicy on the second go-round.

As I cooked, I felt that David was giving me the key to the mysteries of a certain kind of French home cooking. “There are many articles and books written about how French women cook,” he tells us in the story that precedes his partner’s father’s “winter salad” recipe, “but until this story that you’re now reading (and this book), there was very little mention of how men cook in France at home.” The recipe that follows, a breathtakingly simple endive and Roquefort salad, was so good I couldn’t stop eating it. Its magical alchemy tastes like an esoteric, gourmet delicacy whose recipe has been a family secret for 150 years.

But this book is called “my” Paris kitchen, not “the” Paris kitchen, after all; rather than a general overview of male domestic French cuisine, this book is about how David Lebovitz cooks at home. And so we get recipes for quintessentially French food, but also wonderful varieties of hummus and tapenade, Indian cheese bread, shakshuka, and dukkah-roasted cauliflower. What knits all of these dishes together is the strong sense that they’re organically connected in David’s repertoire, and his stories and asides and anecdotes further this impression. These are lived-in recipes, developed and perfected over the years as he cooked at home for his partner and their friends. Like Maria’s cookbook, this one is filled with love: of a country and a culture and a people, a culinary history’s long-tried combination of ingredients and techniques.

After our week with David in his kitchen, I’d regained all the weight I’d lost in my time in Cyprus with Maria. Both cookbooks were spattered, dog-eared, creased, and covered in olive oil and smears of God knew what. Both cookbooks were placed at the forefront of the kitchen cookbook shelf for future, imminent use.

But I have to pick one. And so I choose the one that feels more substantial, more truly literary and classic, the one that welcomed me more thoroughly into its world, if only because the author has lived there for ten years rather than a summer with childhood memories. I choose the one that feels like a future long-treasured friend.

It’s My Paris Kitchen for the win, hands down.

64 Comments

"I did mean tablespoons. The word "garlic" is in the title of the recipe, and it makes 1 cup of dressing. Depending on your cloves, that's 2-3, which is how I like it : )"

Smashing Plates sounds like a great cookbook, but I have to admit that I have been secretly cheering for David's book all along. I received it for Christmas and I have been reading and cooking from it with a great deal of pleasure. That mustard chicken is one of the best dishes that I have made all year. The oven fried frites are addictive, as is the steak with mustard butter that the frites are paired with. We loved the dukkah roasted cauliflower and the croque monsieur sandwich. This is a cookbook not just to cook from but to read and reread and to lose yourself in. David's observations and head notes are wonderful. I especially loved his essay about how he found his oversized kitchen sink and why he feels that it's the most important thing in his kitchen. Looking forward to the finals!

I hope David appreciates the seriousness of purpose that went into his winning this near final round; he is one very funny guy but he also sure knows his stuff. Thanks so much for all your work and for inspiring me to get familiar with both books. I hope the 52 community will see a lot more of your reports.

I feel I now need to get a copy of Smashing Plates so I can run my own Piglet competition!