Who will speak for the poor recipes? The devalued, the demeaned, the dime a dozen?

On the one hand, they’re everywhere—a million results awaiting the most obscure search. On the other, a segment of the cooknescenti would have you believe that to use them is but one moral and aesthetic step away from microwaving a frozen French-bread pizza—that the only true cooking Nirvana lies in leaving the marked road for the wilderness of instinct and improvisation. What’s a guy who wants to cook dinner to do?

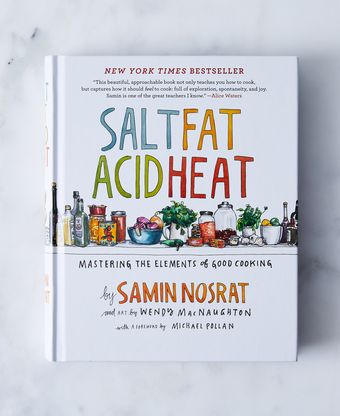

That’s the inevitable question occasioned by the meeting of these two books—Dinner: Changing the Game, by Melissa Clark, one of the most prolific and talented recipe writers of the past twenty years, and Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat, by the legendary cooking teacher Samin Nosrat, which offers the MacGyver-like promise, “Learn to cook delicious meals with any ingredient, anywhere, at any time—even without a recipe.” The italics are mine, but the question remains: To recipe or not to recipe?

In his introduction to Nosrat’s book, Michael Pollan puts a fine point on it: “A well-written and thoroughly tested recipe might tell you how to produce the dish in question, but it won’t teach you anything about how to cook, not really. Truth be told, recipes are infantilizing.”

Truth be told, this is bullshit.

I get it: Following a recipe can, like following Waze, leave you at your destination without any sense of how you actually got there. But while I am personally interested in The Journey, I’m not prepared to dismiss those who simply want to arrive. Pollan can at least be credited with the neat trick of out-condescending something he’s attempting to label condescending. I feel a thousand times more infantilized by his blanket proclamation than by, say, the inclusion of “1/4 teaspoon salt” in a recipe, or a suggestion for the number of tablespoons of oil I might need to cover the bottom of my pan. Those are things more experienced cooks can breeze over, but they remain of use to the more timid or even, god forbid, those with other things on their minds.

Of all the reasons I cook—professional curiosity, familial responsibility, meditative pleasure, straight hunger—the biggest is the simplest: Many days (most days, really), it is the only thing I can look back on as having done remotely well. At any given moment, I can trace an almost direct correlation between the energy and imagination I bring to kitchen and my mental health.The barrier of entry for that fundamental pleasure and comfort should, I’m convinced, be as low as possible. And, in fact, there’s a handy invention to compensate for the varying levels of curiosity, time, interest, fear, and experience of home cooks: It’s called a recipe.

That said. Let me begin again.

I love both of these books. The month or so I spent cooking from both of them was one of the most consistently stimulating, illuminating and delicious I’ve ever had. I think my girlfriend, who shared most of the food, would agree, though I want to stipulate that our daughters were completely useless: The one-year-old eats anything put in front of her with feral gusto, thus making her crap as a critic, while the three-year-old will try nothing that is not pizza, fish stick, chicken nugget or, oddly, string bean. Her sole contribution to this project occurred when I was flipping through Dinner, came upon “Pizza Chicken” and mused aloud, “That sounds silly.” From the depths of the couch, a voice piped: “No it doesn’t.” (She was right; it’s good.)

You could think of this match-up as the New York Times Bowl: Clark writes the long-running “A Good Appetite” column for the paper’s Food section, while Nosrat recently became a columnist for the Magazine. It is also an East Coast-West Coast showdown. I have always thought of Clark, who co-wrote the Franny’s cookbook, as Park Slope made flesh: progressive, kid-friendly, and competitive in the way that might see Dinner as a Game ready to be Changed.

Her suggested list of ingredients to always have on hand—sumac, za'atar, pomegranate molasses, kimchi, sambal oelek—is a sign of both how remarkably far the American palate has come in the past twenty years, and of an author accustomed to easy access to Fairway, Whole Foods, and corner bodegas that are better stocked than most supermarkets elsewhere in the country.

Nosrat, on the other hand, exudes pre-tech-boom Bay Area bohemianism. Recipes pop into her head on the way home from surfing. She mentions her time spent in the kitchen at Chez Panisse the way a Harvard grad manages to work his alma mater into every conversation. (She has the decency not to refer to it as “Berkeley.”) And of course her evangelism for an Eden in which everybody’s ear is attuned to the distinct sputter of a roast chicken at its precise moment of perfect doneness is of a piece with free-spirited, and free-time-filled, Californian utopianism.

It’s true that Clark’s is the more conventional cookbook. I’d say it was the squarer one, were it not so stolidly rectangular. This is the other response to recipe ubiquity, turning recipe books into coffee-top objets. One might think it was a museum catalog, complete with lavish full-bleed photos. Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat is, on the other hand, more like a graphic novel. It signals its difference by eschewing photos altogether, in favor of white space and doodly illustrations by Wendy MacNaughton. If Nosrat would rather not tell you exactly how to make a dish, she’s certainly not going to show you what it’s supposed to look like at the end.

Dinner is, lest the title leave any ambiguity, a guide to what to make for that meal, usually quickly, and nearly always with a favorable ratio of effort to impressiveness. There are a few recipes that could come straight from a list of Allrecipes.com top hit-getters, like that Pizza Chicken, or a casserole of breakfast-sausage, eggs and cheese(also delicious). The book is, for the most part, breezily international, with special emphasis on Middle Eastern and Asian flavors and with little pretense of authenticity. This is one part of how the definition of “American Food” expands. I don’t mean it as an insult when I say that you could convincingly read the table of contents of Dinner as a TGI Fridays menu sent from fifteen years in the future.

Nosrat takes on a completely different mission, which is, in the span of one volume, to provide a universal culinary education. Of its eponymous subjects—the pillars, she asserts, of all cooking—salt is listed first. All I want from life is to someday believe in something the way that Nosrat believes in the power of salt. It is, for her, both science and miracle, by the pinch and the palmful (more often the latter). Aside from its culinary value, Nosrat’s salt section serves as a perfect introduction to her approach: Be Bold, Taste Often.

There are times when the book overpromises. I’m not sure how a page that guarantees “Everything You Need to Know To Improvise A Braise” does so, unless you go seek out recipes for the international range of braises it lists. MacNaughton’s illustrations occasionally seemed to me too cute by half, designed more with information-graphics geeks in mind than actual cooks.

But for the most part, Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat is remarkable. Revelations big and small abound. In the “Acid” section, Nosrat quickly expands that category beyond the expected citrus and vinegars, showing how ingredients like dairy and fish sound similar, or complementary, notes in a dish. She illuminates connections between disparate cuisines that suddenly seem obvious—as in a spread showing international aromatic flavor bases, from the Creole “Trinity” to French mirepoix to West African ata lito, a puree of red onion, tomatoes and bell and scotch bonnet peppers. In one, small, captionless, drawing by MacNaughton, which illustrates the remarkably easy step of removing the bone from a chicken thigh, Nosrat provides a magic solution to the eternal quandary over whether to use whole thighs or the boneless-but-skinless option. It, and the attendant technique of cooking the deboned thighs slowly, beneath the weight of a cast-iron pan—dubbed “Conveyor Belt Chicken” because that is how you’ll want it delivered to your mouth—is something I expect to use for the rest of my cooking life. I’ll pair it often with Nosrat’s recipe for Caesar salad, a satisfying rebuke to dry, flavorless versions served in airports across the world.

Yes, there are recipes. Good ones. Sure, Nosrat would prefer you use that Caesar dressing to teach yourself about acid and salt, adding element by element and evaluating the subtle interactions between them at every step. And it’s a cool exercise. But so is following the traditional recipe at the end of the book. I’d say the same about her versions of linguine with white clam sauce, both of which will make you wonder how it ever came to be the watery mess you find in some Italian-American restaurants.

These two books make splendid companions. One night, I found myself without a lime while making Clark’s Thai-Style Shredded Tofu with Brussels Sprouts, a surprise hit in my house. I cast my freshly Nosrat-ed mind around for another acid component, remembered I had some clams, and ended up adding both their broth and flesh, creating a completely different and, I have to say, pretty wonderful dish of my own. For several of Clark’s chicken recipes, I used Nosrat’s “Conveyor Belt” technique. And Clark has much to contribute to the acid conversation, too: a suggested drizzle of apple cider vinegar brought out dazzling new flavors in her lamb stew.

Of the twenty or so recipes I cooked in Dinner, each imparted a lesson or inspiration. I’ll be using Clark’s technique for a tamago-like Japanese omelet for a long time—likewise, shredding tofu with a box grater so that it cooks up, amidst those Brussels sprouts, as a fluffy, nutty bloom. My inner alarm bells were going off throughout making Harissa Chicken with Leeks, Potatoes, and Yogurt, the cover image of Clark’s book and one of several recipes in which calls for heaping nearly all its ingredients on one sheet pan. I doubted all the elements could possibly cook correctly, without burning or steaming. I was wrong. That dish’s yogurt sauce—an absurdly simple mixture of yogurt, garlic, lemon and salt—became an instant staple.

And yet, and yet. In having to decide which of these two books to advance, I can’t get away from the specialness of Nosrat’s, its scope, its freshness, its idiosyncrasy, its wit. What Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat does, ultimately, is make explicit what good recipes do implicitly: That is, illuminate some previously obscure, dusty, or scary, area of the grand culinary mansion—sometimes a corner, sometimes a whole wing, but always a new place to frolic. Just as it was a beautiful complement to Clark’s book, I’m convinced it would enhance and illuminate any volume it was placed next to, like…well, like salt does to whatever ingredient it encounters. Simply put, it is the first Joy of Cooking or How to Cook Everything of the Google age.

Who will speak for the recipes? I will!

But today I’m choosing Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat.

60 Comments