I am a fairly seasoned home cook but shy about dough; for this reason and more, I enlisted a dear friend, Mal, to come help me judge the cookbooks for the Piglet. Mal is a brilliant baker with an ongoing pie project—the Surprise Pies Club, in which she bakes experimental desserts based on a set of questions for the recipient—and she brought a black-bottomed lemon curd pie for us to eat at the end of the night. It turned out to be the only thing we’d eat all day that didn’t come from Kachka or Six Seasons.

We spent an entire Sunday creating a set of dishes from our two cookbooks. The day’s menu was broken into two distinct courses: lunch, from Kachka, composed of Moldovan Eggplant Salad, Siberian Pelmeni (meat dumplings), and Buckwheat Honey Butter for dipping vegetables. Dinner, from Six Seasons, included Cabbage and Mushroom Hand Pies, Parsnips with Citrus and Olives, and Delicata Squash “Donuts” with Pumpkin Seeds and Honey.

Before starting lunch, we sampled Kachka’s horseradish vodka—which had been infusing over the course of the week in a dark cupboard corner—ice cold, tempered with honey, and mixed into Bloody Marys. Soft with vodka and heady with excitement, we embarked on separate dishes for the first course: Mal began the dough for the pelmeni, and I diced and roasted eggplant for the salad. We kneaded the dumpling dough by machine and by hand; when Mal sliced into it with a knife, she gasped at the texture and called to me to see the tender, cream-colored gap where she’d separated the halves. It was obscenely silky; it took all of my self-control not to stick my index finger into it.

I blended pork, veal, onion, ice water, and salt for the filling. Mal laid the dough down over the pelmenitsa mold, stuffed each pocket with filling, draped a round of dough over it, and took the rolling pin to the whole thing. We were shocked and delighted when bite-sized hexagonal dumplings dropped out of the mold, like magic! The eggplant salad—that exquisite combination of eggplant, tomato, and pine nuts that never gets old—was easy, as was the butter, so the final step before eating was dropping the plump little pelmeni into the boiling water. When they’d risen to the surface, we drained them and dressed them with butter and vinegar.

I was startled by how much I loved this meal. The eggplant salad, cut with the acidity of the tomatoes and studded with toasted pine nuts, was smoky and perfect spread on toasted pita bread; we swiped the luscious, European-style butter mixed with spicy Russian mustard and buckwheat honey onto our plates so we could dip radishes and coins of daikon; the hot dumplings were far more flavorful than their simple ingredients would have suggested.

I realized I had simply never considered food from this region before; or, perhaps more accurately, it was a cuisine I had never been exposed to, and thus had never chosen to try when looking for places to eat. We spent a good deal of this meal chewing with great decadence, helping ourselves to second (and third, and fourth) portions, and staring at each other with shell-shocked, blissed-out expressions.

Once we cleaned up and took a well-needed afternoon nap, we embarked on dinner: the dishes from Six Seasons. Again, Mal worked on the dough, and I made the filling for the hand pies. After assembling them, they had to chill, so in the interim we made the parsnip salad: a glorious mix of satiny, nutty ribbons of the titular root, the salt of oil-cured olives, and the sweet, citrusy burst of eraser-pink cara cara oranges.

But it was the pies that stole the show. The exteriors were flaky and buttery—I could hardly believe we’d made them with our own mortal hands—and the interiors were a warm, earthy mix of cabbage and mushrooms rounded with Worcestershire sauce. We moaned as we ate them, and the next day I finished the leftovers on a train to New York like Maggie Smith ate cold chicken in the carriage to Misselthwaite in The Secret Garden. (Exhausted from our task, we put a pin in the donuts, and I made them later that week; their crisp and creamy texture, hot from the oil and exquisitely salty and sweet, was a singular pleasure.)

We closed the day of feasting with a slice of Mal’s pie and the cacao nib vodka, spirited into sophisticated and not-too-sweet White Russians. The sheer decadence of our day brought to mind my favorite scenes from the Redwall series. (Maybe I’ll get to make Deeper’n’Ever pie, Otter Hot Root Soup, and Rose Pudding next?)

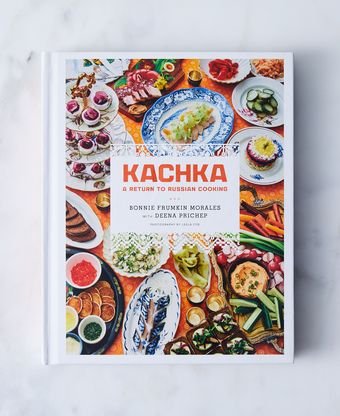

It was only the next morning when I realized the dilemma I faced. Both cookbooks produced delicious food. Both were easy enough for a serious dilettante like myself to cook from while also providing a bit of a challenge. Both were physically beautiful objects—Six Seasons’ matte, debossed cover and stylish, muted photography was gorgeous and trendy, while Kachka’s bright colors, stunning design, and show-stopping endpaper entranced with its boldness. By all of the necessary parameters, both cookbooks fulfilled, and then exceeded, their obligations.

So how to pick a winner? I began to consider what makes a cookbook special, the way you might consider what makes a short story collection special. After all, individual recipes have their value, but a cookbook is a conversation. These cookbooks in particular have the added quality of being the creation of a particular restaurant’s chef, and so the physicality of those spaces, the dimensions and histories of the restaurants themselves, also enter into both projects.

I considered the book’s paratext—or, if not paratext exactly, the material that exists outside of the recipes themselves. I love, for example, that Six Seasons opens with a larder chapter, in which McFadden articulates the necessary items for a well-stocked pantry; it is practical, aspirational, and achievable. I also adore the go-to recipe section, which covers basic sauces and doughs, and later mini-chapters that cover necessary basics like pickling and dressing a salad.

Likewise, I love how Kachka is part memoir; an exploration of the space Russian cooking occupies in Morales’ life. I was delighted that the section about infused vodkas ends with a discussion of drinking culture and a list of toasts, and spreads about Russian markets, pantry staples, and sample menus. I admire how the author approaches the thorny nature of the Russian/Soviet Union diaspora; how she tackles the multifaceted identity of her cookbook’s food in relation to a constellation of nations and peoples, cast against the width and breadth of the region’s history. The text is sharp, funny, playful, and informative, and the biographical opening is beautiful—the story of the origins of the cookbook’s name made my nose tingle like I was about to cry. Against this kind of pathos, complexity, and vision, Six Seasons didn’t stand a chance.

And so, moved by its personal material, emboldened by its ambition, and as satisfied by its offerings as a fat little badger having eaten her fill, I declare Kachka the winner.

45 Comments

Wanting to learn more about what happened in Bobr, I finally found this link on page 3 of Google, but no other historical reference, which breaks my heart: http://shtetle.com/shtetls_minsk/bobr/bobr_eng.html.