Moving is a cruel way of determining what is essential and what is not. This became all too clear a few months back, when I was packing up my cookbook collection for a move from Brooklyn to Austin. I’d never actually counted how many cookbooks I owned, but if you asked my wife, well, it was about 1,000 too many. Everywhere you looked in my two bedroom apartment, there were shelves and stacks of vintage and hot-off-the-presses cookbooks. Can you blame me? During my 18 years of working at Bon Appétit, almost every cookbook published landed on my desk. I was spoiled and in that time I lugged many of them home. But now it was time to purge.

Over the course of a week, I flipped through every one of them and made piles: Keepers, Giveaways, and Holy-Hell-Can-I-Really-Live-Without-These. This was before Marie Kondo went mainstream, so I had my own criteria for deciding which ones to hold on to and which ones to jettison. I would keep the ones that did one of two things: tell an amazing story with recipes and words, or geek out—hard—on one subject. That meant holding on to all my Elizabeth David, Richard Olney, and Fergus Henderson texts. I kept books that have become essentials in international cooking (like Diana Kennedy’s The Cuisines of Mexico and the Tsujis’ Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art, to name just two). And there was no way I would ever give away the 1960s classic, 365 Ways to Cook Hamburger, even though I’ve never cooked from it. In the end, the cutthroat system kinda worked, and I got my collection down to a (somewhat) reasonable number.

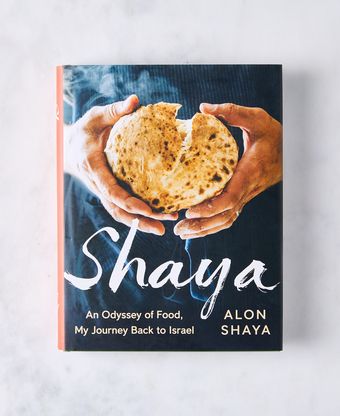

All this is a way of explaining how I was going to approach my judgment for the Piglet. It would be a snap: One of the books would win me over by telling a great story or going hardcore on a single topic, and the other one, well, wouldn’t. It didn’t turn out that way. When I ripped into the Piglet package containing my two books, I let out a “F#^k!” in front of my two young daughters. I was familiar with the two competitors: The Noma Guide to Fermentation and Shaya: An Odyssey of Food, My Journey Back to Israel. Damnit, Piglet! This wasn’t going to be easy.

Obviously, Noma needs no introduction. Its chef, René Redzepi, is, in my opinion, the most important and influential chef since Ferran Adrià decided to put down his knives. I’ve eaten there a few times and each visit was a head-trip of flavors, textures, and presentations I’d never experienced. It turns out that the backbone of what I loved at Noma is fermentation, the ancient method of creating tasty things from the controlled breakdown of food by microbes. Think: kimchi, kombucha, and, of course, wine. Fermentation is so important to Noma that Redzepi set up a lab dedicated to it, run by David Zilber, who shares a byline with Redzepi. “Without fermentation, there is no Noma,” says Redzepi in the book’s intro. I believe that, because this book is a behemoth: 455 pages full of step-by-step photos for recipes that take days, weeks, and months to reach completion. It’s inspiring, but a weekday or even weekend cookbook this is not. I expected this; nothing too simple could be behind the magic at Noma.

Shaya, on the other hand, is a simpler affair but equally as compelling at first glance. It tells the globe-trotting story of chef Alon Shaya who was born in Israel, raised outside Philadelphia, lived in Italy, and made a name for himself in New Orleans, where, until a recent divorce from the Besh Restaurant Group, he operated the award-winning Israeli spot Shaya. He now owns Saba in New Orleans and Safta in Denver. It’s as much memoir as cookbook, with recipes adding a punch to heartfelt and very personal storytelling. Chapters aren’t divided by ingredients or courses but, refreshingly, follow his stops around the globe. Unlike The Noma Guide to Fermentation, Shaya was something I could tackle on a Tuesday after picking my daughters up from kickball—but would it be as fulfilling?

After spending two weeks reading and rereading Noma and Shaya (something I always do first with cookbooks) it was time for a cooking game plan. I dog-eared recipes in each book that I planned to give a whirl. I’m not going to lie, finding recipes in Noma that didn’t take weeks or some speciality equipment to complete proved difficult. That’s not a criticism, just the reality of a book in which time and letting nature take its course is the whole point. I’ve got a decent kitchen setup (and now that I don’t live in NYC, plenty of counter space), but airlocks, dehydrators, fermentation weights, and a pH meter are things I don’t own—yet. You don’t need all that equipment to tackle the recipes, but it does help, and I like buying stuff I don’t really need.

At the Bon Appétit test kitchen, I’d seen firsthand how far down the rabbit hole you can go with fermentation experiments. Brad Leone, BA’s former kitchen manager and star of It’s Alive and its various spinoffs, was a lacto-fermenting madman. There was a whole corner of the kitchen filled with jars and jugs and trays of weird and wacky stuff. I was lucky enough to try a lot and watch how he did it all. Some of it was brilliant, other tests ended up a moldy mess. I needed to keep things as simple as possible.

I’d read an article where Redzepi suggested that the Lacto Blueberries recipe was ideal for beginners, as it required only two ingredients (blueberries and salt), a fermentation crock (I’d bought one at a stoop sale several years back), and four to five days for results. Many of the recipes in the book run over multiple pages (the Pearl Barley Koji clocks in at eleven), and thankfully this one was a mere three. You might think that’s because, like many science-heavy cookbooks, the language is rambling and reads like a biochem textbook. On the contrary, Redzepi and Zilber went to great lengths to make sure the writing was conversational, clear, and as concise as possible. If a recipe ran eight pages, it was for good reason. I have to admit that after a few days with the book, I found the recipes soothing, especially when read out loud to my kids. Words like “SCOBY,” “koji,” and “inoculate” made them giggle. In the end, the blueberries turned out to be transformative. Sour with an underlying sweetness, they were ideal on vanilla ice cream and as a topper on the girls' morning yogurt.

After a boost of confidence from the blueberries, I moved on to kombucha. I inherited a piece of a SCOBY (a raft-like formation of microbes, or that slimy residue you’ll find in most commercial kombuchas) from a chef friend and got to work. I made Apple Kombucha and Mango Kombucha—both of which turned out amazing, with a depth of flavor you don’t find in the overly-acidic supermarket brands.

In another life, I’ll make Koji, a magic mold with unparalleled levels of umami, that's used in Asia to ferment everything from miso to soy sauce to sake. I now know way too much about this mold, but consider it one of the happy results of spending a month with this book. Another happy result is my Yellow Peaso (miso made with peas)—I’ll let you know how that turns out in several months, along with the Celery Vinegar I just put up (will that taste as good as Redzepi and Zilber say it will?). I’ve already suggested to my wife that the laundry room would make for a nice little fermentation lab of our own. She’s thinking about it.

The plan for Shaya was to give the book to a few friends and have them mark their favorite recipes. These would be the centerpiece for a grazing dinner party. Lutenitsa, a charred condiment of sorts made with red peppers and eggplant, was on almost everyone’s list. I have a feeling that the story that went along with the recipe made an impact. Lutenitsa was the aroma that filled the chef's Philadelphia home when he would return from school, a sure sign that his grandparents were visiting from Israel. “I can trace all of my food memories back to one moment,” writes Shaya. As I charred the vegetables on my Weber, I couldn’t help but think of my first food memories: I’d often visit my grandparents in rural West Virginia, where my father’s mother ran a little food trailer called the Tasty Creme. She’d make big batches of sweet-ish chili that would later top hot dogs.

After cooking my way through a few more recipes—Crab Cakes that Shaya cooked in the aftermath of Katrina, Goat Tacos that Shaya made with his cousin, Gideon, in New Orleans before Gideon passed away—I started to realize that the food was almost secondary. It was the stories surrounding it that really stoked my appetite. In fact, even if Shaya had omitted the recipes altogether, I still would have devoured the book. Whether I cooked food from Israel, Italy, or New Orleans, each recipe was rich with memories and anecdotes, which, for me, is the whole point of cooking.

Like I said, working at Bon Appétit all these years spoiled me. Our recipe testing process was tight, and the writing style on our site gives you all the information you need without mincing words. Shaya’s recipes tend to over-explain in some places, and under-deliver in others. The average home cook won’t notice, but this is my curse after years in a professional kitchen. My only other quibble is with the photography. Bon Appétit spoiled me in this area, too, since we employed some of the best photographers in the business. Here, the photos tended to be flat, with little styling, and odd cropping as well. But these are little things, and do nothing to take away from the transporting words of Shaya and co-author Tina Antolini.

The dinner party was a rousing success, evidenced by the fact that almost every guest ordered the book on their phones in between bites of Marinated Soft Cheese, Brussels Sprout Salad with Mustard and Toasted Almonds, and Za’atar Fried Chicken. But there was still one recipe I knew I had to try. Years ago, I’d had Shaya’s now-legendary Whole-Roasted Cauliflower with Whipped Feta, at Domenica, his Italian spot in New Orleans. Now, I wanted to see if it could pass the toughest critics: my two daughters. Could Shaya be the person to get my kids to eat a whole head of cauliflower—and not just by using the “rice” technique, whereby the florets are blitzed in a food processor, cooked down, and cloaked in butter and cheese?

When I brought the charred cauliflower to the table, I ceremoniously impaled it with a steak knife, just like I’d had it at Domenica. The girls were skeptical. But after cutting off a few florets and slathering them with whipped feta, all their fears floated away and they begged for seconds. Success! My daughters’ approval reaffirmed what I had suspected: Shaya’s whole-roasted cauliflower deserves to be in the canon of great dishes that even the average home cook can master. Moreover, this dish had a special meaning: It was Shaya’s proof that America was hungry for more of the Israeli flavors and cooking traditions that he’d been raised on. In a way, it inspired him to open the restaurant Shaya, which established the culinary path he’s still following today.

So, it was decision time. I’m not kidding when I tell you that over the span of a few weeks, I dreamt about fermentation and shakshouka. Actually, I had nightmares. You know those restless nights before a big race or deadline, when you’re half asleep and words and thoughts fill your brain and you wake up exhausted? That’s what it was like.

In reality, both books deserve to go on to the next round, but there are no ties in the Piglet—I double-checked. Decisions must be made. What’s clear is that neither book is going on my giveaway pile. I’ll box them up and take them to whatever city I call home next. The Noma Guide to Fermentation dove deep into a hard-tackle subject, and emerged as a cookbook that will long line the shelves of both professional and amateur chefs. When it comes to capturing the allure and power of fermentation with such clarity and passion, there are only two books: Sandor Katz’s Wild Fermentation and The Noma Guide to Fermentation.

On the other hand, Shaya is a compelling and heartfelt food memoir that is evocative of books by some of my favorite food writers, such as Laurie Colwin, Jane Grigson, and Edna Lewis. Great cookbooks are about so much more than tablespoons and temperatures; they are about individuals, the places they’ve lived, and the challenges they’ve overcome. So, for that reason—before I change my mind for the 98th time—Shaya wins a nailbiter.

16 Comments

BTW F52 Team, bravo for an excellent Piglet tournament. I’ve followed the tournament since the beginning and am thoroughly enjoying it this year.