I think the best cookbooks are for cooking. Is that too obvious?

You see, in the beginning, cookbooks were manuals, economically written and utility-minded: There was a stove and there was a cook, and there weren’t too many other notes in the tune. Now cookbooks might be primers or ethnographies, encyclopedias or manifestos, decorative objects or art books or odes or explorations or branding exercises or mission statements or any number of other things, some of them potentially wonderful.

But can you cook from them? Do you want to cook from them?

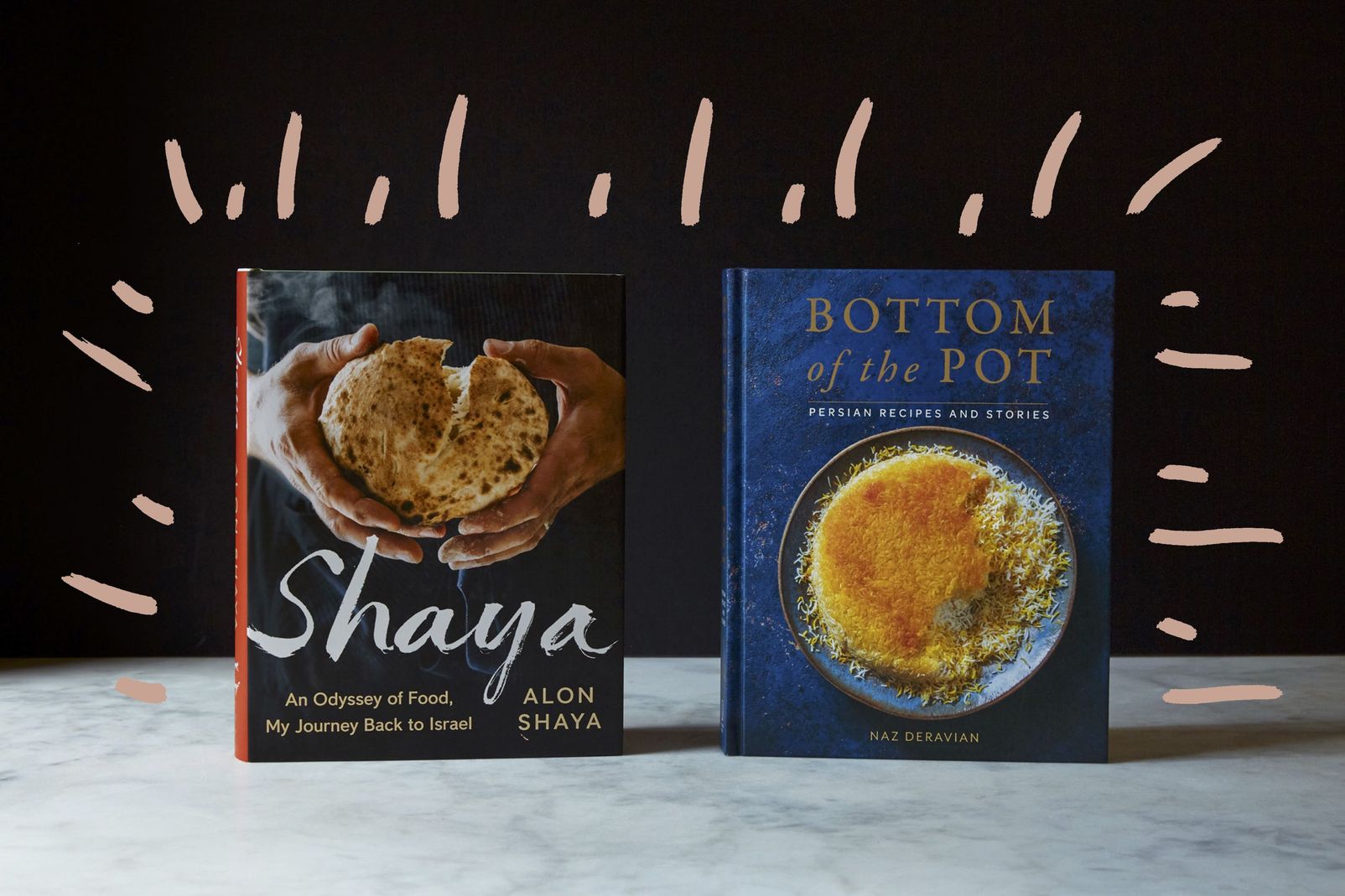

The Piglet couldn’t have planned it exactly this way, but the bracket delivered Bottom of the Pot and Shaya into my hands, both memoirs—or at least memoirish—in that they are deeply and resolutely first person, with long passages recounting episodes from the lives of their respective authors, Naz Deravian and Alon Shaya.

This is especially so with Shaya, the celebrated chef who was born in Israel, grew up near Philadelphia, apprenticed in both Vegas and Italy, and went on to open restaurants in New Orleans. He writes about growing up poor, a child of parents who split up not long after arriving in America; his teenage years were particularly troubled, and then he found his calling in a high school home economics class. The scenes from his life are vivid and sometimes even cinematic, as in the passages in which he flees Hurricane Katrina in a Land Rover with the chef John Besh (his now–former business partner, who has faced allegations of sexual misconduct), two cats, and the contents of a restaurant walk-in.

The book unfurls chronologically, and so it essentially urges you to follow along and cook Shaya’s life, however scattershot the recipes can seem (Blueberry Rugelach, White Asparagus with Eggs and Speck, Lobster Curry, a turkey sandwich). It’s more of an issue in the first half of the book than in the second, once he lands in New Orleans and the dishes begin to cohere. That’s when it all starts to sound really delicious.

And, yes, the food is really delicious. His White Bolognese—a tomato-less variation on the classic—is outrageously good, made with ground pork, chopped fennel bulb, and orange zest and juice. A cup of cream is poured in at the very end, as the reduced sauce quietly burbles toward conclusion. It was exceedingly rich, but also nuanced and bright, thanks to the fennel, orange, and spices.

The Moroccan Carrot Salad was also great. I roast carrots this way all the time (super skinny in a hot oven, rolled with olive oil and salt), but I'd never thought to toss them in a spicy dressing. This one is superb, made with harissa, apple cider vinegar, paprika, and cumin—the flavors are vibrant and clear as ringing bells. And the Yogurt Pound Cake with Cardamom-Lemon Syrup, made with 4 eggs and 6 additional yolks, was soaked with more of that syrup than I would’ve thought it could take, but the directions said to have faith, so I did. The results were moist and fine-crumbed and floral, a cake that wasn’t too fancy for everyday life but subtly special on the plate.

Throughout, the instructions were easy to follow and filled with helpful cues and lively descriptions. Shaya is a little cheffy in its requests—several dishes wrap in various subrecipes to prep first, with particular ingredients and hand-ground spices—and I found few dishes that didn't feel like projects, at least for this working parent. But it's cookable for anyone who is already comfortable in the kitchen and happy to invest the time.

Still, there’s something that doesn’t quite click. Building a cookbook on a person’s life story, rather than structuring it around the actual food, leads to several recipes that are not exactly crying out to be made.

It also puts some pressure on those passages to be very, very good, and ideally explore themes that make the book about something bigger than its author—that’s inherent in the form. The acknowledgments mention Laurie Colwin, a writer I like so much that when I put this book down I picked one of hers up. Even though her writing was personal—and her teeny apartment in Greenwich Village where she did the dishes in the tub, is as real to me as any place in a book—her work isn’t really about her. It’s about life in the kitchen, the ways of thinking about food and preparing it and eating it that will feel familiar to people who care at all about cooking. This book fell a bit short for me in that regard: Shaya is really just about Shaya. If you’re already a fan, Shaya is for you. If you’re not already a fan, you may be wondering why you’re reading.

Bottom of the Pot uses Naz Deravian’s voice differently: It adds texture to the Persian and Persian-inspired dishes that fill the book, bringing a vast, intricate cuisine down to earth. An actress, writer, and home cook, Deravian left Tehran with her family when she was 8 years old, landing in Vancouver and then ultimately moving to Los Angeles.

Her personal stories are interspersed throughout the book, memories of the past that can sometimes be a little gauzy. But Bottom of the Pot doesn’t rely on them for its structure, and they aren’t at the beating heart of the thing. This one is powered by the recipes, which are appealing and approachable and alive. And I was enchanted with the results, which is due both to the cuisine and Deravian’s words.

Her Fesenjan, the traditional walnut-pomegranate stew, was delicious and satisfying to sample from the pot—a few hours on the stove darkened the color of the stew, smoothed out the jangly, puckery flavor of the pomegranate molasses and turned the sauce satiny. The recipe is written in a casual, narrative style that reminded me a little of Nigella Lawson’s work, and the dish was very simple to prep and follow.

I took Deravian’s advice and served the stew with Sabzi Khordan, a plate of tangled fresh herbs, radishes, scallions, and feta, all of it drizzled with olive oil. Why do I ever make tossed salads? Why do I not just do this?

I also made the Steamed Persian Rice with Tahdig, the dish with the resplendently crispy top that’s on the cover of the book. I’d made a version of rice with tahdig before that used yogurt to help make sure it wouldn’t stick, but this would be the first time I did it without that aid. Deravian’s instructions are extremely detailed and clear, and so were the disclaimers; she warned me that if I used a Dutch oven it might not turn out. Well, I used a Dutch oven (I don’t have a nonstick pot) and some of the rice burned and stuck—but I didn’t care. It was still a minor triumph to have pulled it off.

I kept going—the Baghlava (or baklava) Cake was tender and light, a bit of clever home cooking that siphons the flavors of the traditional pastries and transfers them to an easily made cake. I wouldn’t trade it for the real thing, but I’m unlikely to make the real thing at home anytime soon, either. A weeknight salmon dish had a soy–maple–dill marinade so good, I sipped it from a spoon; the dill rice I made to serve with it was, in a word, heaven.

Cookbooks are for reading, sure—but they are, above all, for cooking, and should call you into the kitchen. The winner here was clear for me.

13 Comments