I got my Piglet books over a particularly cold, miserable couple of weeks in New York, when it was dark by 4:30 in the afternoon. Naturally I went straight for the wintry soups and stews, like Joanne Chang’s hot and sour soup made with ground pork and squeezes of Sriracha -- her mother’s recipe, a flash of Chang’s Taiwanese upbringing -- which turned out beautifully and tasted even better the next day when I warmed it up for lunch.

Chang runs an empire of cafés in Boston and though her second cookbook has plenty of savory recipes, the finest thing I made from it was the kouign amann, a killer pastry from Brittany that holds more butter and sugar in its layers than seems physically possible. I’m comfortable with laminated doughs like puff pastry and croissant, but I’d never attempted a kouign amann before. It’s a bit messier, since you’re pouring sugar into the last few folds, and I wasn’t entirely sure about the pinwheel-esque shaping, but I loved Chang’s voice here, guiding me to seal the folded dough under plastic wrap as if “you were tucking it into bed.” And the idea of baking the pastries in muffin tins is kind of genius; it’s perfect for home cooks without silpats and rings, though I did find some problems with them sticking at the bottom, and it’s much trickier to maneuver a palette knife into a grooved tin than a flat sheet pan. But never mind, the pastries were gorgeous! Dark golden brown and wonderfully crisp on top, with tender, buttery centers and caramel-covered bottoms. The recipe could have used a few process shots of the folding technique to help cooks along, and to show the ideal texture of the dough -- it’s very hard to know if it’s too dry, or too wet, in the early stages without some frame of reference. That said, I trust Chang enough after my kouign amann experience to try her bûche de Noël recipe on Christmas Eve.

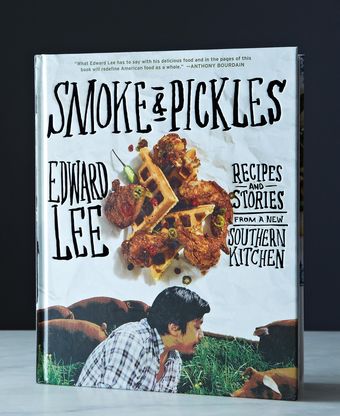

“Sometimes it’s better to just leave an ingredient out rather than to substitute an inferior version,” warns Edward Lee, who’s been cooking in Louisville, Kentucky for almost a decade. It’s a fair point. There’s nothing more annoying than complaints from cooks about recipes they didn’t actually follow (“I used buckwheat flour instead of all-purpose flour and it sucked!”). But I couldn’t find a pheasant. So I guiltily made Lee’s pheasant and dumplings recipe with turkey around Thanksgiving -- the meat simmered in a roux-thickened stock and white wine, shredded and served with some zingy dumplings seasoned with fresh horseradish. It was wonderful. I got right into his recipes for kimchis and pickles, too, and appreciated the handful of step-by-step shots on the more complex recipes. But mostly I wanted to sit down and read this cookbook like a memoir, so I did.

I have a soft spot for hybrids, for idiosyncratic food that doesn’t fit too neatly into a single tradition, and Lee’s book tells the story of a chef who explored his own Korean traditions and those he adopted in the south to come up with something of his own. It gets really personal -- one of my favorite moments in the book is his self-deprecating look back at the night he cooked for Jeremiah Tower and Tower rejected the food, forcing Lee to reconsider his path as a chef.

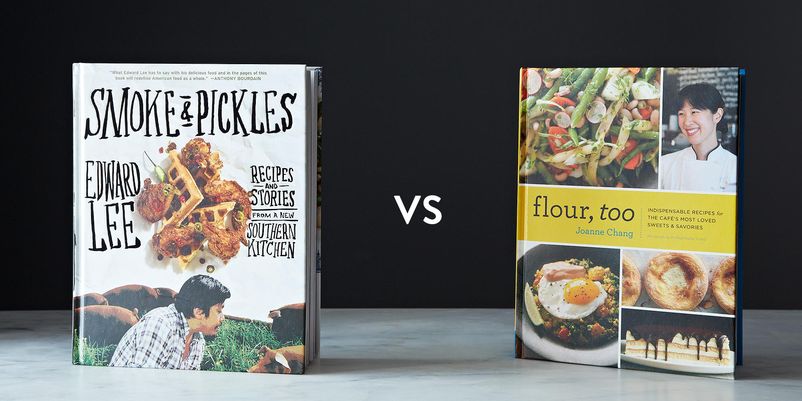

Both of these cookbooks make you want to get in the kitchen, and reward you with great things to eat if you follow their directions, but they also have the chefs’ portraits on the covers, promising their stories will be inside. In the end, I wished Flour, Too had made room for more of Chang’s stories in between the lovely recipes. Pressed to choose, I go with Smoke and Pickles.

62 Comments