BAM! That’s the sound of a great regional American cuisine being reduced to a cliché. But don’t blame Emeril; the same thing happened in the 80’s, when Paul Prudhomme unleashed a national epidemic of blackened catfish, from which chain restaurants across the country are still recovering. For some reason, the food of Louisiana seems destined to be eternally misunderstood.

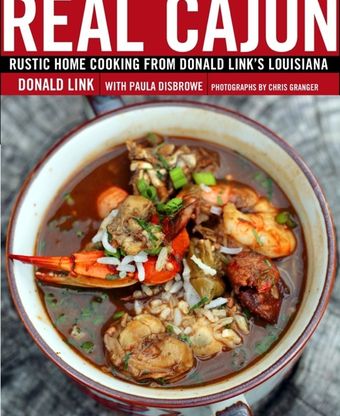

This fall, two cookbooks, My New Orleans by John Besh and Real Cajun by Donald Link and Paula Disbrowe, should go a long way toward restoring the rich culinary traditions of Creole and Cajun cooking to their proper place in the American pantheon. Both books were written Post-Katrina, and are imbued with a reverence for local foodways that the authors fear might fade away. There are similarities between the cooking styles of Besh and Link, but one important difference: Besh covers both Creole (fancier, more restaurant-style food) and Cajun (more rustic) cooking, while Link focuses exclusively on Cajun food.

John Besh started out cooking in New Orleans, and then went to Europe to train in kitchens there. When he returned, he opened the elegant restaurant August in New Orleans, followed by Luke, Besh Steak and La Provence. He grows some of his own food, raises his own pigs and chickens, and primarily buys from local suppliers whom he knows. His book is a mostly successful attempt to capture what he calls “the food of here.”

My New Orleans is a gorgeous book. Color photographs of the food are interspersed with black and white historical pictures, and Besh describes in loving detail many of the local dining rituals. His prose is heartfelt, and throughout the book he scatters many gems, like the story about Tabasco, the famous Louisiana pepper sauce. His red beans and rice recipe is perfect, simple, a dish I could eat every week. The fried artichoke recipe calls to mind the famous preparation of the Jewish quarter in Rome, the classic version of trout amandine he includes is exemplary and the grilled corn on the cob with crab butter is genius.

At over 350 pages, My New Orleans is perhaps too ambitious for its own good. The editing should have been tighter – too many sentences begin with unnecessary flourishes like “Be aware, too,” and "Go ahead and.” And it lacks some basic copy editing, like checking to make sure that the source for “Steen’s Cane Syrup” is, as it is supposed to be, on page 362. (It isn't.) More jarring was a self-aggrandizing chapter about Besh’s victory over Mario Batali on the television program “Iron Chef.” It reminds the reader that, although he is a New Orleans native at heart, his stature and appeal are bigger than the city where he lives. Not endearing.

And sometimes his intentions run ahead of his technique. He talks about preserving freshness of flavor in a strawberry gelee, but then instructs the reader to heat all of a strawberry puree to dissolve the gelatin. Standard operating procedure is to heat only a small amount, thereby keeping the rest uncooked and more vibrantly flavored. He has a neat trick for testing the sugar level of a sorbet base – floating a whole egg in it – but nowhere in the recipe does he suggest tasting the mixture. “There are no restaurant recipes here,” he writes, but “Crawfish Agnolotti with Morels” and “Louisiana Blackfish with Sweet Corn and Caviar” (with a foamed sauce) are not what I’d call home cooking. Likewise, I scoured the terrific map of Louisiana in the front of the book, which shows the provenance of all of the local ingredients used in the recipes, but I couldn’t find any black truffles, which make several appearances.

Real Cajun, on the other hand, is pitch-perfect. It sets more modest goals, which it amply fulfills. Donald Link, another local boy made good, is the chef and owner of Herbsaint and Cochon in New Orleans. Link’s family were rice farmers who emigrated from Germany to the Southwest part of Louisiana known as Cajun country. The photographs and text, like the recipes, speak simply and directly of that place.

Cajun country produces rice, crawfish and pork, all represented in abundance. I appreciated the step-by-step instructions for making sausage, one of the most important pork preparations in Cajun cooking. Dish after dish, I found myself nodding in agreement: dirty rice, chicken and sausage jambalaya, grilled oysters with garlic-chile butter, smoked bacon and giblet gravy. This is food I’d like to cook – and eat.

Link is my kind of chef: he’s clearly talented enough to create dishes designed to impress, but he doesn’t. Instead he writes recipes that are clear, smart and easy for a home cook to follow. His time in California has given him a lighter touch than many other New Orleans chefs, like when he suggests finishing rich sauces with a squeeze of lemon juice for brightness. And Link spends a lot of time talking about the most important (and too often underemphasized) cooking ingredient: salt.

Mature regional cuisines are more than just an aggregation of recipes, of course; those recipes are like stories passed between generations, connecting people to each other and to the world around them. Link and Disbrowe capture -- wonderfully, touchingly -- what gives those dishes their meaning, like the story of the gumbo that Link cooked for his grandmother’s funeral. Thanks to Link’s disarming voice and co-author Paula Disbrowe’s deft touch, by the time I finished his book I understood more than his personal history and interpretations of regional dishes -- I knew, and trusted, his palate.

Four years “Post-K,” as Link puts it, much of New Orleans’ future remains uncertain. The physical rebuilding of the city has lagged behind expectations, and some of its cultural bedrock has shifted. But if Besh and Link are the new faces of New Orleans cooking, then there is also much to be hopeful about. They are both talented and passionate cooks who are dedicated to preserving and enriching the cultural heritage of the place where they grew up. My New Orleans is more impressive in scope, more beautiful, more at home on the coffee table. But when I’m cooking at home, it’s Real Cajun that I want in my kitchen.

5 Comments