I once got into an argument with a female novelist who shall remain nameless. At least I call it an argument, but it was really just her having tons of fun at my expense. I was doing that thing that she claimed only men do: calling one novel my favorite and another the best. “You men and your stupid bullshit about favorite versus best,” she said. She was totally right, of course, but it hasn’t stopped me from doing it. (Hatful of hollow—fave! The Queen Is Dead—best!) And now, here I am passing that same kind of judgement over two cookbooks. No, I’m not yet saying which is which, because then you wouldn’t need to read the review.

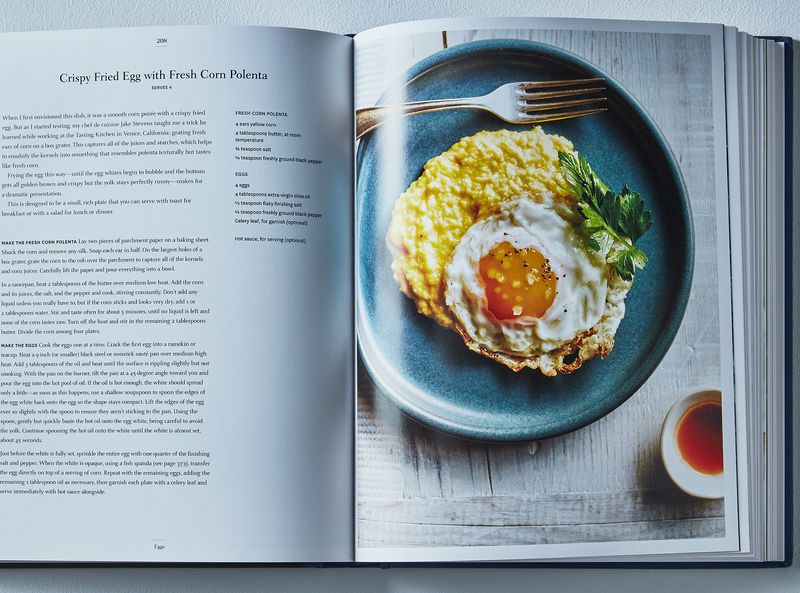

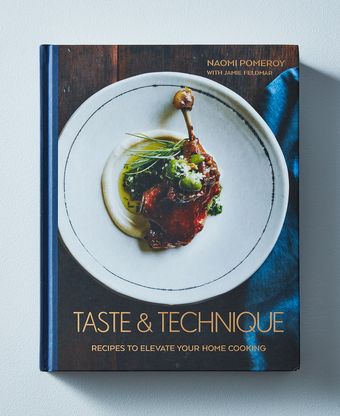

So it’s weird. There were times when I was totally frustrated by Naomi Pomeroy's Taste & Technique, written with Jamie Feldmar. There’s even a recipe, a relatively simple one for Porcini Braised Chicken Thighs, that I tried three times—and sort of failed three times. On my third try, I told my guests that it was blackened chicken in a white wine, carrot, and celery sauce, which they totally bought. They also loved it, which is saying something good, but not necessarily for the book. Other recipes I tried: Hazlenut and Wild Mushroom Paté (success!); Kale with Quick-Pickled Apple, Gruyère Crisps, and Creamy Dijon Vinaigrette (easy-to-make vinaigrette, but my cheese guy, who has been in this for years, had no idea what cave-aged Gruyére was); Crispy Brussels Sprouts with Pickled Mustard Seeds, and Lamb Scallopini.

And yet I found myself picking it up often for the same reasons I just as often put it down. This is what we talk about when we talk about intimidating cookbooks. The subtitle says “Recipes to elevate your home cooking,” but it is not that kind of book. Home cooking has to always take into consideration the realities of the home, chief of which are limited budgets and limited time. And yet Taste & Technique, while sensitive to both, is still not too concerned with either. These recipes demand time and patience. They call for ingredients that are sometimes out of reach for ordinary cooks, like the aforementioned cave-aged Gruyere, and juniper berries, which you can’t always find at your local Whole Foods. And they require a vigilant eye on several details of the process which of course leaves too many areas for a dish to fail—or rather for the cook to simply say “fuck it” and come up with something close. (Or rename the dish.) I get the feeling from its prose style (very exact in its requirements and instructions), that improvising out of necessity—essential in any budding cook’s developing of her own style, or at least saving dinner—would not be cool with the writers of this book.

Also, with the attention and care each dish demands, it was difficult to cook more than one dish at a time, and I had help. Taste & Technique is a cook’s cookbook. It’s no surprise that Pomeroy’s training came from reading cookbooks, meaning, reading other cooks. I get it—I have been called a writer’s writer and it’s a compliment. But it’s a compliment that comes at a cost. I set out to be a reader’s writer, not a writer’s; and this book sets out to elevate home cooking, not Momofuku’s. When I pictured myself, the ordinary cook, who had seven guests coming over in 3 hours, I frequently abandoned a dish midway and just added whatever was in the kitchen. But when I imagined myself as a potential chef (maybe for Momofuku) with time on my hands, Taste & Technique became revelatory. I couldn’t see these dishes in a regular family kitchen—people simply don’t have that kind of time. But I could see it as essential reading for any good cook who wants to become great.

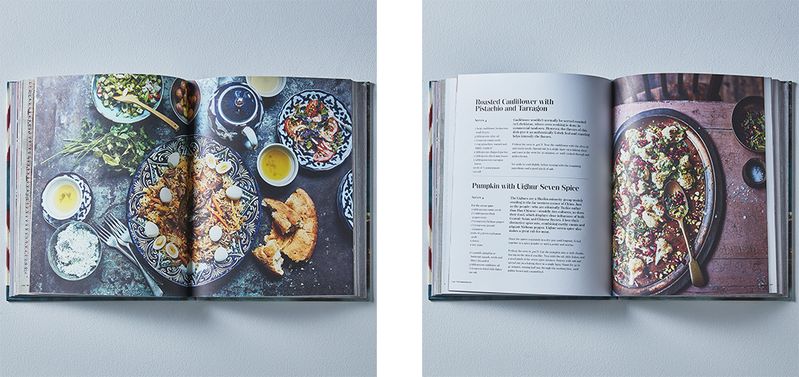

Samarkand: Recipes and Stories from Central Asia and the Caucasus, by Caroline Eden and Eleanor Ford, already assumes you’re great. But great in the sense that you’re a culinary adventurer and are attracted to newness more than anything else. It’s food as adventure tour. The book’s introduction compares Samarkand to Babylon, and Rome, highlighting its exoticness. In many ways, cooks are the original orientalists, cultural appropriators with a free pass, sampling and incorporating the food and flavors of other countries and peoples, but not much else. But so what? Food in itself is the result of culture copulations and clashes. Even salt was once an exotic flavor. So as Turkish, Afghan, Russian, and Chinese cultures clashed, they also cooperated and the results are the dishes in this book.

Samarkand had a radically different mission from Taste & Technique. It seeks out to demystify food to an audience that has become both more and less adventurous as it has become more and less aware. Everybody wants a burrito, as long as it’s Chipotle. Everybody wants some spicy fish paella, as long as you go easy on all those spices. But the bigger mission of this book is to prove that foreign food is both exotic and not exotic at all—meaning it’s both a world away and right within the reach of your own kitchen. Or more simply, that something new is right at your fingertips, waiting to become something regular. A book like this, at its best, can shift your normal.

Or at the very least, it allows you to stop and marvel over titles like “Mountain Jew Omelet.” The staple dish is called khoyagusht, which sounds like something that would send you running to Denny’s instead, but is really just butter, onions, turmeric (so paleo), paprika, chestnuts, and eggs. You will serve your friends Tarragon soda, as I did. You will wonder, as I did, why everybody isn’t sprinkling every single meal with Adjika, a spicy pepper paste from Abkhazia which I made as part of the Spicy Meatballs with Yogurt dish. It’s a wonderful book, but it’s similar to an absolutely wonderful date, where despite having a great time, you don’t wake up wondering where he is and when you’re going to see him again. Which meant picking back up Taste & Technique.

In Taste & Technique, cooking comes across as more science than art. This is not a bad thing. Artsy fartsiness and faux exoticism has killed many a cookbook. People are simply looking for formulas that produce tasty food that their friends will like. But technique in this case also means practice. You can be assured that you will get none of these dishes perfect the first time—that’s the point, and ultimately what the book does very well. It elevates ordinary cooking into something way more than ordinary, through practice. The cook in me that just wants some magic to happen between the time my friends say they are coming over and when they actually do might find himself making only the kale salad. The cook in me that knows deep inside is a James Beard Award winner picks something out of this book, keeps his mouth shut about all the foraging he will have to do, sets aside all other concerns in the world, and starts cooking, hoping that this time the result will be something spectacular. Or if not, then something I can rename to something else, and totally blow my friends’ minds away.

My winner is Taste & Technique.

61 Comments

I walked up to my local Whole Foods this morning. As expected, the cave-aged Gruyere was piled high, right next to all the other cheeses from the Alps. And there were the juniper berries, easy to locate in the alphabetized spices.

Partially, it’s a proliferation of ingredients. Walking home, I was thinking about how much my mother, gone for more than 30 years, would have reveled in the availability of Swiss and other European cheeses. She was the only person I knew who could make cheese fondue from American grocery store Swiss and not have it separate.

On the other hand, juniper berries? Mom could run down to the A&P for them. We may have been limited to iceberg lettuce in the grocery stores of my youth, but we had a few more ingredients than you’d think.