King Solomon’s Table and Kaukasis spotlight Jewish and Eastern European food, respectively. Each exhibits an intimacy in storytelling and asks the reader to invest in its dishes’ historical and geographical context. Both books are notable for their authors’ personal affinity for the places they write about.

Joan Nathan is a well-known and (rightfully) celebrated cookbook author. She’s an unmatched intellectual on Jewish food, with a process more akin to cultural anthropologist than cook. At 74, she’s accumulated a lifetime of stories and recipes from cooks across the global Jewish diaspora and shares them in the pages of her 11th title, King Solomon’s Table.

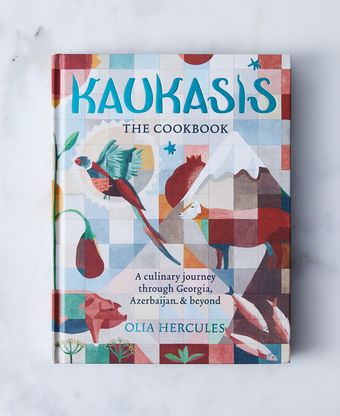

In 1986, at the age of three, Olia Hercules, a London-based food writer and stylist, went on a life-changing family trip. It was a twenty-six hour car ride from her native country, Ukraine, to Azerbaijan—a former Soviet republic bound by the Caspian Sea and Caucasus Mountains (for which the book is named). This journey was both the impetus and inspiration for Kaukasis.

The first recipe I chose to cook from King Solomon’s Table is Azerbaijani Kakusa with Swiss Chard and Herbs. It’s how Nathan begins the book, and seems like the logical choice to compare apples to Azerbaijani apples. The kakusa, a cooked egg concoction, is conceptually straightforward. I am comforted by its familiarity.

This one is overloaded with bitter greens, added after you sauté onions and herbs in oil. Which is sorta my issue with the recipe. It assumes that all greens contain liquid, which, in the case of my chard—the ingredient named in the dish—it did not. Chard is liquidless. It needs more braise than sauté. Even though my leaves were destemmed and cut into formal squares, the residual steam of the allium mixture was not enough to cook them through. My chard situation still needed a considerable douse of water. Otherwise, it would’ve burned before it finished cooking.

I’m given the same instruction for chard as for its suggested alternative, spinach, as if the cooking methodology for one applies to the other. It does not. Under different circumstances, this omission would’ve rendered a simple and gratifying dish unpalatable, with greens unevenly cooked. I cook with all of my senses, and have the confidence and recall of one who’s done so for years. In other words, I knew what to do. By making the requisite adjustments, I was able to enjoy a dish that was everything I want from frittata and quiche, but never get from either.

On the other hand, a very redeeming and worthwhile recipe in the book is an uncomplicated and impeccable carrot salad (“Indian-Israeli-Style”). It goes like this: in a food processor, pulse carrots, garlic, hot pepper, and herbs. Scrape it all out in a bowl, and add lime, julienned green bell peppers, olive oil, and chopped pistachios. Mayonnaise, we’re told, can be added as an alternative to olive oil. I scoffed at this “choice” and coated the carrots in slightly more than the recommended 3-4 tablespoons oil.

The results would be delicious as a salad or condiment. But I wasn’t feeling the bell pepper addition. Following instructions, I cut them into strips—an aesthetic and functional burden on the dish. (My preference would’ve been to dice.) Still, overall, the recipe is a surprisingly delicious foundation that you’ll be grateful to build upon.

On to Hercules’s Kaukasis. The Soviet occupation of that titular region (i.e. Caucasus) was catastrophic for its food culture, erasing the ancient and nuanced regional traditions in favor of homogenous industrial food. Farms were destroyed and many recipes—buried in the minds of elders—were lost. This book feels like an earnest reclamation of that missing history. (This was also the impetus for Hercules’s first book, Mamuska.)

There’s a succinct introduction, and then straight to the recipes. The ingredients are mostly recognizable and in some cases, I found the components easier to prepare than pronounce. There are sauces and condiments that build from prior sections of the book.

As a native Georgian (of the U.S. variety), I was particularly taken by Hercules’s fermented green tomato. Our tomatoes have no problem ripening in the summer, but harvesting them early, cutting them into rounds, dipping them into an egg wash, and dusting them with floured cornmeal before frying has been the breadth of my relationship with green tomatoes. As a fermentation enthusiast, I found Hercules’ green tomato pickle simple but revelatory. It’s a new favorite condiment.

To make it, you flavor a salt water brine with peppercorns and bay leaf, then bring it to a boil. The tomatoes are quartered in a way that they just barely remain intact. Sliced garlic cloves, chili, and celery leaves (could be subbed with parsley, I think) are stuffed into the incisions. The stuffed tomatoes are crammed into (sterilized!) jars and the infused salt water poured over the top. Now, because it involves fermentation, this recipe takes two weeks to prepare. But on the bright side, you’ll have a ridiculously delicious condiment for at least twice that long, that can be enjoyed with meats, cheeses, in white beans, on toast, on khinkali. It’s a hell of pickle.

I’m a little sheepish about my next recipe selection: Cauliflower steak gratin. Considering this is such a cool cookbook, full of dishes that most of us know very little about, my pick might seem a little lethargic. If I were to artfully defend myself, I might cite a tenet from my own culinary doctrine: The simplest things done best are the most appealing. I find joy and wonder in extracting divine flavor from the ancient and rudimentary.

But also, I’m busy. Most of my home-cooked meals lack industry, and that’s what I like about them—and why I chose this simple and familiar cruciferous dish. The recipe begins with a skillet-searing of the vegetable “steaks” in a combination of butter and vegetable oil. I like to do the same, except I’ve always done it in brown butter, and where I might pair it with hazelnuts, Hercules brings in cheese, raclette or Ogleshield, specifically; it may be cumbersome to procure, but it’s melty and worthwhile. You incorporate it into a mixture of egg, garlic, spices and—if you wish—sauteed onions, then you pour it on top of the seared “steaks” (now in a gratin pan) and send it to the oven. I opted in on the onions and am convinced their residual heat helped to soften the cauliflower as it cooked, the same way it did in Nathan’s kakusa.

Now, I have been to the Republic of Georgia twice, and I really like Georgian food. Because of this, I wondered if this book would justly capture the immense charm and character of the region. I know I struggle to. I’m happy to report it wildly exceeded my expectations. The selection of dishes goes beyond Georgia to represent other bits and pieces of Caucasian cuisine like Ossetia and Romania. Hercules is a chef and a food stylist, and it’s her recipes, in tandem with her arresting imagery and enchanting dedication to the food of Eurasia, that give Kaukasis a special feeling. The combination captures the contemporary gastronomic revolution of the region, which, as is the case worldwide, defined by young people reclaiming their traditional foodways, in kitchens and on farms, and with respectful liberties, making it their own.

Of course, Nathan set the bar on respectful culinary excavation years ago. It’s thanks to cookbook authors like her that Hercules has a foundation upon which to build, update, and personalize. When it comes to dissementing the historical context of her vast geographical and cultural purview, Nathan is lavish. This is fascinating, but if unencumbered utility is what you fancy in a cookbook, you will not be charmed by the deviations in King Solomon’s Table. At times, Nathan’s display of knowledge becomes an avalanche. It is so expansive, that the book can swerve, crashing into historical narration that can be hard to follow. No doubt the web of recipes and stories connects more precisely in her deeply wrinkled brain than on the pages. If I’m exposing my own intellectual ineptitude in this critique, I am prepared for the negative remarks. I’m not confident I can discredit your analysis.

I hate to pass on such an iconic food scholar as Nathan, but I’m going with Olia Hercules's Kaukasis, which feels like a rewarding cookbook addition for even moderately engaged home cooks.

27 Comments

So he made a frittata ( or as he puts it "a cooked egg concoction") and a salad from the first book, and a green tomato pickle and a cauliflower steak from the second book. Are these really representative of these two cookbooks and the cuisines they cover? No real main courses? No desserts? Is he an ovo-vegetarian? Was he too busy to give these books the reviews they deserve? He does confess to being a lethargic home cook whose meals lack industry. Why exactly was he chosen to be a Piglet reviewer? Why exactly did he agree? Mostly I blame my disappointment on Food52 for selecting this reviewer, not having higher standards for the reviews, and for allowing this review to be the definitive statement comparing these books!

https://food52.com/the-piglet/2018/bracket

(I had a devil of a time finding it also)

@nancy - thanks for the link.

When I evaluate a cookbook, I look for recipes that scream at me, "Make me! Make me!" Particularly in the case of "King Solomon's Table," the reviewer did not sound like this was the case for him.

I'm very familiar with Joan Nathan's work, and this seemed unfair.

However, his review did make me interested to explore Kaukasis.