I edited this cookbook tournament for five years—and yet, when it’s my turn to judge, I make the same mistake I’d cautioned scores before me not to: I skip the introductions of my two books and dive right into the recipes. It’s a mistake, you see, because these preambles frame everything. They make you a promise—this book will help you cook smarter, or it’ll make you believe that you, too, can live and cook glamorously from the French countryside. And that’s what we evaluate the book’s success on: Did it live up? At least, that’s what I wrote to our Piglet judges, year after year. And each of them probably rolled her eyes at me, eager, as I am now, to be made hungry.

Momentarily halted by the overwhelming desire to poll all 75 of those judges, I got to Post-Iting recipes like mad, feeling thrilled, even a little illicit, by breaking the rules I had for years enforced.

Tartine All Day’s recipes weren’t giving me quite the same rush—that is, until I got to Mollet Eggs. My hastily jotted Post-It reads: "Mollet eggs! Good god, I thought no one could teach me a new egg!" Problem is, as I paged through chapters of perfect-looking sides and salads—a Post-It opposite the Purple Salad, a lovechild of tweezer-arranged appetizers and figs-on-a-plate cuisine, literally reads “-_-”—I couldn’t find a lot more that elicited exclamation points. (Save for maybe that fried chicken that uses chickpea flour.) I couldn’t see, yet, why I should care about most of these recipes. Defeated, I trudged back to the beginning to contextualize everything—to learn why this book, why now.

In the six-page section I’d initially skipped, titled “Why This Book Now,” I read about author Liz Prueitt’s philosophy of home cooking (that the work you put into cooking “becomes part of the meal’s pleasure”), and how she got to where she is now, as a professional cook and owner of Tartine in San Francisco. She writes about her gluten intolerance, and how it drove her to create and invent and test new flours. She’s written three books, but this one is different: Not only has Prueitt collected recipes that she and her husband Chad Robertson, Divine Leader of the cult-followed Tartine bread, like to cook everyday, but she also guarantees approachable methods and successful outcomes. She promises this book will be an “inspiring guide to integrating new ingredients and old techniques into the daily tempos of our busy lives.”

So let’s skip past the Buttermilk-Herb Dressing I made first, which didn’t really inspire me to integrate anything new into the daily tempo of my busy life, though it was perfectly approachable and very good tasting. Her Celery Root and Citrus Salad inspired enough for the both of them combined: A creamy celeriac remoulade served alongside a bitter and bright citrus situation was, flavor-wise, pretty revelatory, though it was also the most awkward-looking dish I’d made in months. (Picture: Two separate piles, one plate.)

Prueitt formats her recipes the way The Joy of Cooking does, where you’re presented with your ingredient as you’ll need it in the cooking process. This gives the book a pleasant narrative feel—it’s the way I think we’re really meant to read recipes—but as I cook, I wish for even more narrative, more specificity. It’s the structure I appreciate, not necessarily the way Prueitt has implemented it. Like in that revelatory salad, I’m supposed to make a vinaigrette from the juices of the citrus membranes I have left behind, but how much juice, approximately, should I end up with for a balanced dressing? Then: I had about half of the vinaigrette left over when I was done—was that my mistake? No? Okay, how should I reuse it? I picked up the slack on the lack of instructions for how to julienne celery root, but I’ve worked in food for almost a decade—my partner would have needed to turn to Google.

When I made Prueitt’s Any Day Pancakes, having never made pancakes with almond flour, tapioca starch, oat flour, and brown rice flour, I wondered if lumps in the batter were okay, or if it should have been uniformly smooth. Also: Can I overwork these flours the way I can gluten flours? The pancakes came out pretty good, though, and I liked the tips for making the mix ahead of time, which I suppose I should really do now that I have my body weight’s worth of alternative flours hogging my fridge door.

The Pork Chops in Mustard Sauce with Apples asked me to season the chops, but didn’t provide a marker for how much. (A simple “two-finger pinch” would have been great! I am not asking for the moon!). I wondered if I was supposed to pat the chops dry before I seared them (they’d accumulated a lot of moisture), or what kind of pan Prueitt liked to use (other than one that’s “large enough”—oh right, thanks!), or at what temperature they’d be done (what if I don’t yet have a “desired doneness” for pork chops?). The finished dish was so delicious I ate the leftovers, cold, out of the fridge for two days straight.

Having eaten enough food for a good-length hibernation already, I cut her recipe for a two-layer birthday cake in half, feeling, as I measured out the gram weights of 5 different flours, like a low-key drug dealer. Again I felt the same am I doing this wrong? anxiety that had struck me when I followed the pancake recipe. The finished cake tasted so much like raw nut flour that I carried a piece a mile so that a pastry-cook friend could check my math. I wasn’t halfway down her steps when I got the text: “I would be so upset if I went to a birthday party and this was the cake.”

Aside from the oddly bitter, lingering aftertaste of that cake, I was left with a yearning for more of Prueitt’s guiding hand in the recipes themselves. Tartine All Day has an airiness about it: The perfectly-lit photos and the pictures of Prueitt herself on some back deck, flipping a steak, make you want to jump into the thing, or at least onto that deck for a dinner with her. So much so you almost forget she never did answer those questions you had. If these recipes are indeed what she loves to cook everyday, where was she? Why didn’t I feel like she was with me as I cooked? Maybe you don’t want that guidance, or you don’t need it—you can fill in the blanks on your own and you’d rather. For everyone else, it’s unlikely you’ll be able to integrate these new ingredients or old techniques into the daily tempos of your busy lives without a second reference.

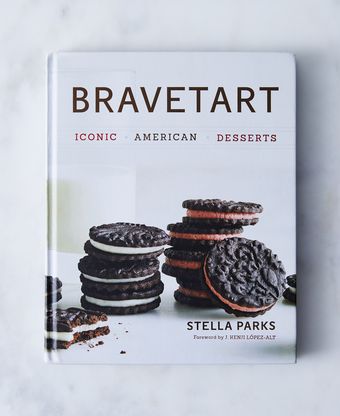

I turned to Stella Parks’s BraveTart: Iconic American Desserts, dedicated to “midnight snacks” (respect), feeling relieved to find a simple one-page introduction. Parks is a pastry chef in Lexington, Kentucky, who’s been recognized lately for her work there as well as for her blog (that’s where the name of her book comes from), but you may also know her from her column on Serious Eats. She gets right to the point: “I’m not here to ‘fix’ American desserts because I don’t believe they’re broken.” She’s here, she says, to make them more like they ought to be: unfussy, reliable, scratch-made, and with all the classic flavors you remember from growing up. But she’s also here to remind you where they all came from. Most recipes in this book are preceded by an archeological dig, what she calls “culinary time travel,” which explain exactly how each is an integral part of American culture. I gripe at the end of her preamble, but only mildly (If I had a dollar for every time a cookbook author expressed the hope that this book will become ‘splattered and dog-eared'...) and read on through her requisite “how to use this cookbook” sections.

Unexpectedly, these sections are a joy to read. Instead of being told “I love this brand of OXO measuring cup because, I don’t know, I just really do, it’s all I use!” I’m schooled on why a pound is not a pound. And not just that all AP-flours aren’t created equally, but why they aren’t, and what the differences are, and what the most versatile brand really is. (If you don’t have it already, as I didn’t, go get thee some Gold Medal bleached all-purpose, Parks says.) I’m taught all of this in a voice that feels new, fresh—all the things we mean when we media people annoyingly and obtusely call a story “voicey.” See: “I’d like to go back in time and punch the guy who decided to give two entirely different systems of measurements the same name.” Okay, Parks. I’m listening.

The very first recipe in her book, fittingly, is for chocolate chip cookies. And as promised, before you get to her version of them, you get the delightful historical rundown. It starts with how we even began baking with chocolate in the first place (the falling price of chocolate at the turn of the 20th century paved the way for at-home experimentation). And it leads to Parks’ eventually—and thoroughly (the woman bought a 19th-century rasp at an auction to accurately test the recipes of our foremothers)—debunking the common myth that chocolate chip cookies were invented in 1938, the year Ruth Wakefield published her recipe for Toll House “Chocolate Crunch Cookies.”

Because I believe that testing a chocolate chip cookie in a baking book is like ordering a margherita at a new pizza place—if they fuck this up, they’re not to be trusted—I made them. The recipe was concise, yet anticipated every question I had: How soft should the butter be? (65°F.) And the refrigerated dough, if I decide to make it ahead? (70°F.) And it was honed—not your average, back-of-the-box recipe: Use chopped chocolate, not chips, and oh, here are 7 variations you can play with, from browning your butter to imitation, super-crispy Famous Amos-style cookies, to making these gluten-free. Just like Parks said, the finished cookies improved upon what I ate as a kid, but only a little—a chocolate chip cookie should never stray too far from your memory.

Park’s Snip Doodles (the historical precursor to snickerdoodles!) were a relative breeze, even though grating a cinnamon stick felt like trying to saw down a tree with a microplane, and even though I did accidentally dip my measuring tape into the batter as I tried to follow her fastidious directions. (Related: If you’ve ever wondered, as I have, where the name “snickerdoodle” came from, Parks will tell you.) I also tried her Make-Ahead Whipped Cream, solely because I didn’t believe it’d stay pert for 8 hours. (It did. For 5 days.) Her No-Knead English Muffins will probably make their way into the normal rotation around here. And since there was a classic yellow birthday cake, I thought it only right to try this one too. Parks uses potato flour to make it super light, and indeed it is—though wrapped in plastic for a day or so, the whole thing got denser, a little sticky. I’ll admit here to not making the frosting, but the crisp photos by Penny De Los Santos didn’t force me to imagine what the whole, finished cake would look like, all blanketed in chocolate. Throughout, the pictures serve as a guide (should my edges be browned?) and as a bit of welcome Americana (hello, Little Debbie Oatmeal Cream Pies).

The scope of work in this book is staggering: These are history lessons sourced and detailed enough to take your average writer-pretending-to-be-a-journalist (hi, it’s me) a solid week of research. BraveTart isn’t just full of very good, if not better, versions of American classics, plus excruciatingly-tested recipes for them; it’s also full of stories that allow us to revere distinctly pleasant parts of American culture in a time when it can feel conflicting at best to do so.

The best cooks, like artists, often subconsciously work toward a signature style, the goal being that if we read a recipe or take in a paragraph, we have an idea of who authored it. Prueitt’s work has had this stamp for years: A perfectly lovely sable, but it’s made of buckwheat and is entirely gluten-free? A butterless chocolate cake that’s as rich as its fellow all-butter peers? It’s got her name all over it. But with Parks, “stamp” seems too inconsequential a word. She’s not simply owning a category of recipe, she’s going much deeper. She’s teaching us things we never knew about the foods and dishes we’ve put on pedestals in this country for decades. And she’s making them better, both with sharp tweaks and by deconstructing them for us—by telling us why they work. Birthday cake, but made with potato flour for fluffiness? We’ll come to know that as a classic Parks. But better: Give me the headnote, the “culinary time travel” that it chronicles, and I’d be able to tell you she wrote that. We’ll come to know her voice, too.

The effort that Prueitt put into Tartine All Day is clear—how else do you end up with a solid gluten-free pancake recipe that calls for 25 to 50 grams of three different flours, plus a hint of tapioca starch? Taken on its own, it does a fine job of living up to its promise, for the right kind of cook. But the thing about BraveTart is that I couldn’t find a single flaw. And as someone who’s sent back, at minimum, dozens of Piglet judgment edits asking for an equal representation of both books’ missteps, believe me, I looked. Parks doesn’t just live up to the promise she made; she adds to that fulfilled promise a vast amount of historical research, and then performs the equivalent of writing it upside down on a ceiling. And there’s no beating a masterpiece—not in this fight, anyway.

45 Comments

My husband loves dessert, and I think secretly wishes I would bake more. And I want to make him happy, but I am intimidated by baking. The precision, the strict adherence to a recipe without room to make it my own, the inability to fix a mistake on the fly without having to start completely over, following rules without understanding why the rule exists.

This review makes me want to buy Brave Tart, certain I'll discover within its pages why something works and how to apply that knowledge in other baking applications. It makes me feel confident I'll not only be able to make something delicious for my husband, but to put my own spin on it and make it mine. In short, this review has assured Brave Tart a spot on my bookshelf.

I love reading all of the historical and cultural notes in the side bars, but I am most impressed with the quality of Sax's recipes, and the book has earned my trust to the point where I can make an untried recipe and serve it with complete confidence.

I bought the book after Jennifer Reese, the author of the wonderful blog Tipsy Baker, wrote about it.

Food Cake in Boston last fall, and was blown away by her knowledge and ability to explain complex baking procedures and ingredients in such simple terms. (We had a baked sugar testing!) Such an amazing teacher! Brava! Congratulations on her well deserved win!