The difference between Lobel’s Meat Bible and Michael Ruhlman’s Ratio is a telling guide to what kind of cook you are. Do you want an encyclopedic approach, an authoritative selection of recipes across cuisines? Or do you want a culinary rulebook, deconstructing recipes into basic parts for you to manipulate at will?

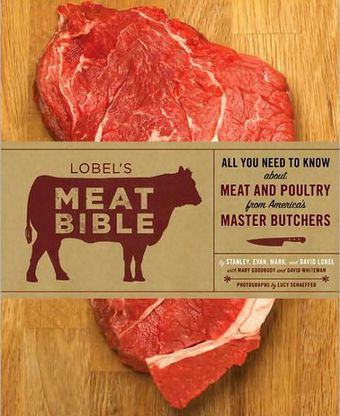

Lobel's Meat Bible, you can assume from the title, aims for the former. And the Lobels are a New York institution, so they’ve got the chops (literally) to back it up. In fact, the Lobels may have the reputation for one of the best meat shops in the country. Their commitment to quality cuts and old-fashioned service stands out — one of the few things to survive the cult of the cellophane-wrapped chicken breast.

My father used to take me to their shop as a young boy on special occasions -- which is to say whenever he felt he could afford steak tartare. “This is the real McCoy,” he would say to me as we stood facing a mountain of meat and a nodding butcher (a real butcher, with the blood stained apron and nicks and scrapes on his exposed forearms to prove it). My dad’s recipe? Eat it right there at the counter, “where it’s freshest,” he'd say. After asking the perplexed butcher for a “touch of salt,” away our fingers would go, into the small cardboard container of just-ground meat. It was a primordial moment, and my memory of it is that the meat tasted cold, salty, and delicious.

The Lobels had me with nostalgia and a straightforward embrace of great meat. The Meat Bible's structure is simple to follow: each chapter is dedicated to a particular protein, with an introduction to the different cuts and a list of recipes. For the enthusiastic carnivore, it’s a proficient account of meat in its many forms, with glossy shots of oil-slicked True Texas Chili and Indian Style Fritters with Lamb. If those recipes sound a bit incongruous, they are. But then again Lobel’s has adapted to changing times and our globalized cuisine. I found the book’s global approach at once too far-reaching, and too Americanized, with retro-sounding recipes like Beef and Spicy Tahini Casserole and Chinese Chicken Salad.

Likewise, the introductions are helpful, but a bit shallow. Lamb neck, for instance, is mentioned as a sweet and tender “Other Cut,” but the Lobels see it fit only for hamburger meat. (You can tell they’re loyal to the chop.) If you’re looking to acquaint yourself with whole-animal cooking, you’d be better off buying Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall’s The River Cottage Meat Book — a superior execution of the same idea.

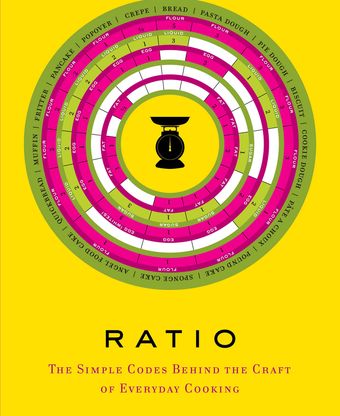

Then came Michael Ruhlman, who offers a different but no less ambitious approach to cooking, taking on the role of culinary code breaker. In Ratio, he makes it clear that while cooking is an art, it’s a science, too, governed (like most everything else) by a system of simple proportions. Chefs can extemporize in the kitchen for the same reason that my grandmother could recite the recipe for pound cake: they understand the relationships between ingredients and the ratios that make them work.

Call it the cook’s scripture — or, as Ruhlman puts it, “A Periodic Table of the Elements for the Kitchen” — the source of their alchemic capabilities. Here, Ruhlman uses it to demystify everything from pickling to the perfect pastry crust. Cookies, for instance, are as simple as 1-2-3: one part sugar, two parts fat, three parts flour. With that foundation, he explains, you can build countless variations, of which this book lists quite a few. That’s something The Meat Bible can't match, even with the perfect steak: your own cookie factory.

Ruhlman's concept isn’t new, necessarily — it’s another way to explain the classic technique inculcated by any culinary institute. And it’s not a perfect science. When he applies his “ratio” concept to things like consommé, for instance, it you can sense its shortcomings. (Ruhlman himself confesses these limitations: “It should go without saying that for more flavor you can increase the quantity of meat and vegetables. Additional aromatics are also advisable…”) But he still succeeds in making these fundamentals more approachable for the home cook, helping to distill the essence of everyday recipes.

Like Harold McGee before him, Ruhlman has given us a great book for the thinking cook — for anyone seeking to look beyond the recipe. To some, that kind of approach may sound intimidating. To others, liberating. Either way, it’s an essential step in truly understanding the craft of cooking. With Ratio, cooking becomes something at once intellectual, intuitive, and infinitely improvisatory. Which is a lot better than even the best Beef and Spicy Tahini Casserole, in my opinion. My nod in this round goes to Ratio.

5 Comments

Dan

I think that comparing these two books is a bit of stretch. I work as a charcutiere on a grass farm in Pa. for a farmer who bought the Lobel's Meat Bible thinking that he would learn something about butchery only to discover that it was a cook book.

The title is misleading as the book is far from a comprehensive approach to explaining how to handle meat.

I think the only thing that Ratio and "Meat Bible" have in common is that both have titles that imply that the reader will be treated to a discourse on food and cooking that promises to be didactic instead of the usual telling or retelling of recipes common to most cookbooks. Only Ratio is didactic while Lobel's Meat Bible is a recipe book.