Peter Meehan: I feel like a good place to start with cookbooks is White Heat. It’s definitely inspiring to you in a way that it isn’t to me. Why? Why has it inspired so many cooks? Why do you guys like it so much?

David Chang: ‘Cause it looks cool. At a certain point, recipes become sort of pointless -- not pointless but, like, how many recipes of the same thing do you need to read? It’s more about conveying a certain philosophy, a certain moment in time. Obviously not all recipes become pointless; certain books need recipes. The book you’re working on with Wylie Dufresne -- that’s going to need recipes. You know?

PFM: At different points in your life -- as a professional or home cook -- you’re going to need more recipes. But for you, personally…

DC: Recipes have never been that big of a deal. I think it’s more of the how. I think the most important thing is the thought process and the food philosophy. What you get out of White Heat is the intensity of trying to just get it right. No matter what. The food that he does is dated: It doesn’t look good anymore and it’s really hard to execute well. But you get to see a guy and his team in the moment, trying to be number one, in a way that is black or white. There’s nothing really styled in the first section of the book. It’s all about the stories. And that’s what is most important to me in a cookbook: conveying a story. If you can convey a story, it’s a book -- not just a cookbook. Cookbooks like that are ancillary for me.

PFM: Was there ever a cookbook that you learned from?

DC: The French Laundry Cookbook. The reason why wasn’t the recipes -- very few people actually made the recipes -- but because it told a story of perfection, and the pursuit of perfection, that captured the mind of every young cook. No one had ever seen a story like that.

PFM: And of home cooks, because no one had ever seen a story like that. It promised perfection was a place you could get to by working and following these steps.

DC: But the home cook is like, “I need pictures.” The only non-picture cookbook that I really like is On Food and Cooking.

French Laundry gave you an insight into what was possible in cooking. Before it, cooks didn’t know what the ceiling was. And then all of a sudden it was like, “Oh shit. It’s really far away and I don’t think I’m ever going to reach that level.”

PFM: Like the brunoise page, that page with all the cuts.

DC: Yeah! That’s one of the best things ever. You’re like, that’s the actual size? Those are the actual cuts? What the fuck? How? And then you realize: That’s how they actually really cook. And that’s one of the most amazing things. It mythologized Keller. It made it seem impossible to actually reach that lofty standard. All good books need to transport you; they need to make you dream.

PFM: What about non-western European stuff? I feel like Japanese books were important to you early on. Were there any books you couldn’t read but you could look at and try to piece together what the cuisine was made up of?

DC: Ramen cookbooks. I hired someone to translate them because I had no idea what they were saying. I had no starting point, I had no idea what the ingredients were. I remember putting an ad on craigslist.

PFM: Is this pre-Momofuku?

DC: Yeah. I got the person I hired to tell me the steps and the ingredients. It was another world that I didn’t understand. And the pictures were very how-to and they were great.

Japanese cookbooks are amazingly technically proficient but they just can’t capture the magic. Seiji Yamamoto’s cookbook is amazing but, for instance, his dessert of blown sugar makes it seem like it’s possible. [Laughs] What it should show is that it’s impossible and you’re never going to make this. The only way to make this is to be a ninja like him and his staff. I can’t read Japanese, so I don’t know if it’s saying “Don’t do this!” But the pictures are like, “You can do this.”

PFM: The genius of Japanese cookbooks is the workaday, step-by-step photographs to make every kind of soba dish, for example.

DC: I recently bought one about mochi; I can’t remember the name of it. I got it for the guys at Ko. It’s a very step-by-step process. The book transports you, it opens up your mind to something that you didn’t think was possible, similar to what White Heat does. It’s like, “Oh! This is impossible. I’m never going to be as cool as he looks.” [Marco Pierre White] was the first person to look cool and gain everyone’s respect.

PFM: Up until that point, everybody looked like the Swedish chef?

DC: Right. And every great cookbook was different. White Heat, French Laundry -- those two are the motherlodes. Obviously the Ferran cookbooks are just in another league. But I would say Albert Adria’s first two cookbooks are unbelievable because they let you into the mindset of someone who is working on a whole new level that you’ll never get to. It’s not like, “Look at me. I’m so amazing.” Instead, the book exists just because he wanted to document.

PFM: Did you ever get into Pierre Herme’s first book with Dorie Greenspan? My wife learned so much about pastry from that.

DC: Never did. Heston’s The Big Fat Duck Cookbook book was great -- but only if you’ve been to The Fat Duck. What Heston’s book is best at is something that other cookbooks don’t do -- they never pay credit to all the other places that they’ve stolen from. Every cookbook has been influenced by another cookbook; every recipe has been influenced by another recipe. Neither comes out of your fucking head like Athena. What Heston’s book does better than any other that I know of is it gives footnotes like a college dissertation. That was fascinating, because you’re like “Where did that come from?” If you just read the footnotes, you learn a lot.

That’s the thing a lot of cookbooks forget: the process of learning how to do something. How the author of the cookbook learned how to actually make the dish, where the inspiration came from. Everything’s already been made before, multiple times. How many recipes for roasted carrot salad and shit like that do you need? It’s the mere going-down-the-rabbit-hole thing, like, “I didn’t know that one of Heston’s favorite books is one of my favorites too.” Great Chefs of France is one of these amazing books, and the reason I like it is because it gives me an insight into all the great nouveau cuisine chefs, from the Troisgros brothers to Bocuse. How they made their menus. A day in the life of each of these kitchens. It’s just the best. I don’t think there are any recipes to make out of it, but that’s not what you need. You’re already replicating recipes in the kitchen. You need something to inspire you to dream, to become an independent thinker. Teaching you how to think. That’s the best.

PFM: Showing you how to become an independent thinker and then what it’s like to share that, right? Because it’s one thing to be great at cooking, but it’s another thing to be able to talk about what you do and share it in a way that people can learn from.

DC: And it’s definitely from a professional’s point of view.

PFM: From a professional’s point of view, what do you think about these two Piglet books?

DC: We need to come up with new photography, man. I don’t know. Like I hate our cookbook.

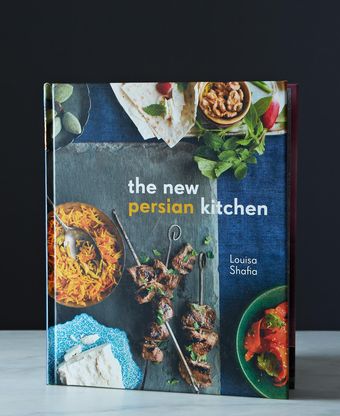

I don’t know anything about Persian food. I think The New Persian Kitchen is a great home cookbook, and that it has something to teach a professional cook like myself -- getting a better understanding of flavors that I don’t know, for example. It doesn’t pull me in and take me to Persia, but I don’t have a frame of reference. If I had been to Persia and had the food, then maybe.

PFM: Maybe throw in some landscape shots so you know where that dish is from? Everything in the book is shot in a studio.

DC: The Roberta’s guys really capture what Roberta’s is and the philosophy behind it. I guess both books do on some level.

PFM: It’s cool that they got to put a spread of them dirt biking in the cookbook. We tried to do stupid shit like that in our book with the same publisher and they never let us.

DC: I think that’s what they wanted to do. It’s a tale of two different kinds of cookbooks. They’re hard to compare.

I like Roberta’s Cookbook book but personally I’m more interested in the stories and the logs of failure than the actual finished product. I thought Rene Redzepi’s book [A Work in Progress] was really interesting because it was just all failure.

That to me is the most interesting. I think that you have to look at it from two perspectives: one as a home cook, and one as someone who has seen every cookbook and has an extensive cookbook collection.

I’m looking for something that’s going to blow my hair back, that I’ve never seen before. Maybe that’s never going to happen, but what I’m ultimately after is that White Heat-like woaaaah. I want someone to challenge me to be like, “You better fucking work harder, Dave.”

74 Comments

This Piglet Tournament was my first, where I truly checked out most of the books to review along with the judging. Loved the temp of the tournament...until we got to the final. This format was disruptive to the rhythmn of the contest. I really was enjoying the 'ambiance' and discussion of all these great books. But then out of nowhere, it was like you threw a monkey wrench into my groove. Like others, it felt anticlimatic and thoroughly confusing. Reading through the interview with David Chang, I thought "WTF?! They're not even talking about the 2 books". It also felt like the announcement of the winners was an afterthought, which seems a bit insulting to the winner. Anyhoo, that's just my take. I look forward to next year, but I hope you don't do structure the final in this format again. Even with a intro, the interview does not really belong here. Perhaps at beginning of the tournament...