I have watched with clenched-teeth jealousy as all of my pastry-loving friends got to dig into sweets book after sweets book by David Lebovitz over the years. (Sorry, I'm just not a dessert person.) And I've followed his blog since nearly its earliest days, (Was it really 1999? Did the internet really exist then?), marveling at the fact that despite how often he cooks it, he's never released a book of savory recipes.

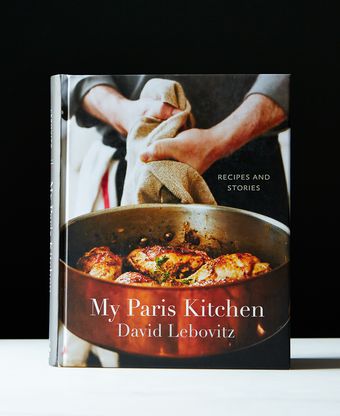

Which is why, when I received both Bar Tartine: Techniques & Recipes and My Paris Kitchen in the mail, I turned to the latter first. My time has finally come, and what a fun time it is! Lebovitz is one of the rare cookbook writers whose essays and musings are at times more exciting than even the recipes or the gorgeous photography. As I thumbed my way through My Paris Kitchen's 300-odd pages for the first time, I couldn't help smiling every time I turned to a recipe-free page, because I knew I was about to be treated to a short story that was equal parts magical, humorous, and useful. On one page you might discover that the French don't eat kale (which, in turn, makes you feel pretty good about not getting enough frisée aux lardons or snails in your diet), while on another you'll find that not only is it okay to put ice in your wine on a hot day, but you'll have a few good laughs reading about it in the process.

All truly great cookbooks have to have a few things. They need recipes, sure -- and with the number of recipes flying around on the internet these days, they better be damn good recipes to boot. Check. Lebovitz’s recipes are not just well-tested and delicious (his chicken with mustard is divine!), but they're written in a style that makes clear exactly where you need to be precise and where you have a bit of room to improvise or take a break for a glass of iced rosé. Tossing green vegetables with the garlicky parsley butter generally reserved for snails, as he recommends in his Green Beans with Snail Butter, is a revelation. I'll be tossing all my green spring vegetables in that butter from now on, thank you.

Great cookbooks also need lasting, actionable information that'll actually make you a better cook day to day. Check again. Lebovitz's pantry and kitchen guide doesn't break new ground, but it does a heck of a good job of explaining not just which mustard you should have in your kitchen, but more importantly, why. Personality? Check. His book, like all of his work, is brimming with it. He's your host, your guide, and your partner in crime in the kitchen and around town, simultaneously showing profound respect for his adopted country while playfully challenging traditions and reveling in the looks of quoi? that his American questions earn him from French colleagues. For me, this is what good cookbook writing is all about: I want to feel welcomed and excited. I want a friend in the kitchen, someone who is not afraid to admit the many mistakes he's made along the way and the many more he'll surely make in the future. I don’t want a demi-god who was born with a fish spatula and pepper mill in hand.

Lebovitz has always had a gift for exposing the truth about French home and bistro cooking: That it's not really all that hard; that what makes it special is its simplicity and its ability to deliver powerful, comforting flavors; that it has a real sense of time and place without the need for exotic ingredients or complex techniques. As a recipe developer, I know the difficulty in trying to produce a blueprint that will allow a cook of unknown skill level and -- more importantly -- with an unknown level of access to ingredients to recreate a dish at home. Lebovitz convinces us not only that we should want to cook his food, but that we really can. His recipe for lentil salad with goat cheese and walnuts, for instance, forgoes any pretense of stuffiness: All of the ingredients cook together in the same pot, and it's infinitely adaptable. Once you've got the basic technique down, swapping out different cheeses, nuts, and aromatics in the vinaigrette is straightforward. I like this kind of empowerment from a recipe.

Bar Tartine, on the other hand, is more difficult to love -- which is not to say that there isn't plenty to love about the first book by the team behind the fantastically delicious and inspiring San Francisco restaurant by the same name. Nicolaus Balla and Cortney Burns are the quintessence of the modern DIY (okay, let's just call it hipster) movement; and Chad Robertson, the mastermind behind my favorite bread in the world from Tartine Bakery, is a fantastic partner and photographer.

Where Lebovitz's book is homey and inviting, Bar Tartine is rarefied and daunting. The array of techniques drawn upon -- drying, smoking, fermenting, and pickling before you even get to the first actual recipe in the book -- is unparalleled in its breadth for a book of this size. Where Lebovitz tells you what types of paprika you should stock in your pantry, Balla and Burns tell you how long you should be drying your own chiles to make it. And where Lebovitz's book can take a traditionally technique-heavy dish like confit duck and distill it into a simple and delicious one-pot, no-practice-required meal, Balla and Burns' iceberg wedge salad clocks in at a whopping 31 ingredients, 10 of which require you to first follow recipes in other sections of the book. To be completely honest, I couldn't complete one single recipe exactly as written from this book -- none of the pickled or fermented products would have been finished in the time frame I had to read and write this review! (And my wife would’ve had a fit if I insisted on leaving the slow cooker on for two weeks straight with whole heads of garlic in it for their black garlic recipe.)

These are the kind of folks who make quite literally everything from scratch. For aspiring home cooks who've always wanted to make their own smoked blood orange peel powder, kefir cheese buttermilk, or rice koji powder, they reveal all, providing everything but the cute mason jars with hand-written labels to pack them in.

It's no doubt fascinating for fans of the restaurant or armchair cooks, but many of the techniques presented in the "Techniques" section that comprises the first half of the book are useful only in a restaurant setting. How many home cooks are going to find enough uses for dehydrated huitlacoche powder to warrant making a batch? And more importantly, where is the inspiration that's going to drive me to want to do it in the first place? If you're lucky enough to have eaten at Bar Tartine, perhaps that'll do it for you. For the rest of us, it's not so obvious -- and much of the writing in the book doesn't offer a lot of insight.

Actually, I found the weakest part of the book to be the writing, which, aside from short recipe and chapter introductions and the actual steps for recipes, is verging on non-existent. Balla and Burns clearly speak the language of food, but translating it into the written word is where they stumble. With intense, multi-day preparations and obscure ingredients, I need to really be convinced that something is going to be worth my while before investing in it. For the type of folks who are going to use this book -- and I count quite a few of my friends and acquaintances among them -- making the huitlacoche powder is a thrill in and of itself, regardless of what dishes it makes its way into afterward or how it was described before you began. But to me, a few good words is worth more than even the prettiest photos -- or the thrill of accomplishing a new DIY technique -- when it comes to inspiring me to want to cook something.

Where Lebovitz weaves paragraphs of poetry around simple ingredients so you can taste them before you even start cooking, Balla and Burns' basic recipe intro formula boils down to three perfunctory sentences -- and they rarely describe what you should be expecting out of the finished dish.

On the one hand, I find Bar Tartine’s kind of no-compromises approach extraordinarily admirable. Someone has to keep flying the banner of real food in an age where most folks consume their meals in the form of square-cropped JPEGs, and having tasted the food at the restaurant, I can say without any hesitation that Balla and Burns are the real deal. But at the same time, I wonder whether the book is really written for their audience or for themselves. Any book that describes ingredients like cucumber flowers, mouse melons, sprouted fenugreek, and kefir buttermilk as "inexpensive and easy to source" (really!) makes you wonder whether the authors have ever been outside of a five block radius of Bi-Rite Market.

This solipsism manifests itself in other ways, too. In their “Techniques” section, there are detailed instructions for how to make bottarga, a dried, salted fish roe that you'll have to have tasted to understand what the end product should taste like -- no words are spared in describing its flavor. But the real question is, after procuring fresh gray mullet roe and Himalayan sea salt, cleaning and curing it, then finding a chamber in which to maintain 12° C and 75% humidity for 5 to 7 weeks, drying the roe, then storing it in the refrigerator for a month: What do I actually do with it other than shave it over beef tartare dressed with homemade salt koji?

It's stuff like this that really tears me up about Bar Tartine. The chef, traveler, photographer, and adventurous eater in me gets bursts of excitement and joy with every turn of the page. But the recipe writer in me, the one whose day-to-day goal is to get more folks into the kitchen, can't help but wish that the recipes offered more in the way of compromise -- a reassurance, say, that my soup will come out okay even if I use store-bought apple cider vinegar instead of making it myself.

As someone who has eaten at Bar Tartine, it’s reason enough for me to go through the laborious process of fermenting ramps next spring so I can incorporate them into the mayonnaise that I'm going serve with smoked-then-fried potatoes. But a great cookbook can't rely solely on the legacy of its restaurant to back it up. For the record, I did a test run of those potatoes, but because of the aforementioned slow-cooker problem, I left out their signature black garlic. And because they’re out of season, I left out the pickled ramps. The recipe also asked that I make my own rice vinegar -- I did not oblige -- and fry the potatoes in hard-to-find rice bran oil (I used peanut oil). They were still tasty, but I've got to admit: As a seasoned cook and recipe writer, even I was afraid I might have been altering too much. Bar Tartine: Techniques & Recipes is a gorgeously photographed, lovingly constructed reference, but David Lebovitz's My Paris Kitchen is one of my favorite books in years.

76 Comments