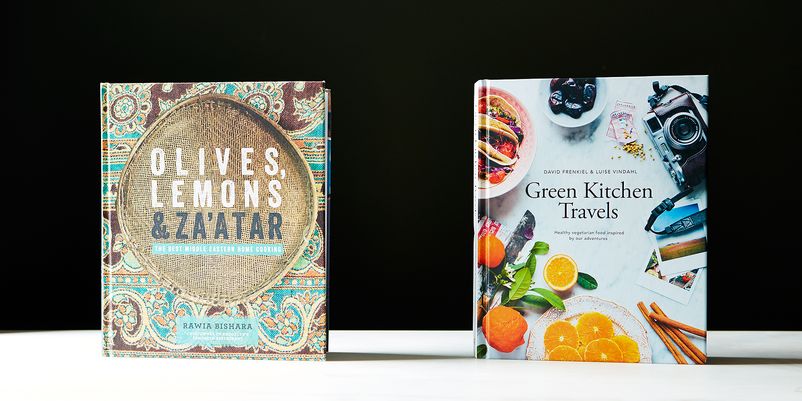

Two regal cookbooks packed with stunning food and travel photos arrive in the mail. One is written by a Danish-Swedish couple who live and blog in Stockholm, and the other is by a Palestinian-Arab restaurateur who lives in New York. Okay, I think, two quality cookbooks to dig into. Easy peasy. But when I crack them open, I realize that Food52 knows me too well. They’re making me choose between my two great loves: fresh and healthful vegetarian food, and contemporary Middle Eastern cooking.

I stopped eating meat when I was a teenager, and am still mostly vegan when I cook at home. Over the last several years, though, as I’ve explored my Persian heritage through food, I’ve cooked lamb or chicken at least once a week. Although it’s an essential part of Persian cuisine, eating meat still feels strange to me. So when I open Green Kitchen Travels, a collection of vegetarian recipes inspired by the authors’ world travels, I feel a sense of revelation. This is how I want to eat again, like back when I lived in San Francisco: meals full of fresh fruit, vegetables, and whole grains. Now that I think about it, I’m tired of browning onions and searing meat. I dive in.

In the “Food Philosophy” chapter that opens Green Kitchen Travels, husband and wife authors David Frenkiel and Luise Vindahl describe their approach to food as centered around “vegetables, good fats, natural sweeteners, whole grains, legumes, seeds, nuts, and fruit” -- words after my own heart. Then, after a brief introduction, they devote three full pages of text to traveling with kids. They’re experts on this subject: They have an adorable daughter whose transformation from infant to little girl is documented in photos throughout the book. While Green Kitchen Travels is ostensibly a collection of recipes, it’s also a manifesto with strong viewpoints: Don’t eat animals; get to know people from other cultures; and travel is a child’s best education. Personally, I like that the authors have such an opinionated stance. Combined with the many photos of their attractive family in various locales, however, the advice can make it feel more like a lifestyle guide than a cookbook.

Happily, the recipes I made from the book were excellent and original. The standout was the Double Chocolate Rye Muffins, made with rye flour, coconut milk, maple syrup, olive oil, and dark chocolate. They were fluffy and moist, with bits of chocolate that oozed onto my fingers. And luckily I can get locally grown, stone-ground rye flour at my farmers market in New York, which gave my muffins a varied, whole-grain texture that made me feel virtuous about eating what was basically chocolate cake.

The Halloumi Veggie Burgers were also exceptional. The instructions, like everywhere in the book, were easygoing and free-form, written with confidence that the reader has some basic kitchen chops. Most cookbooks walk you through every step of a recipe in order to avoid confusion; if this were one of those cookbooks, I'd expect something like, “Divide the mixture into six portions, and shape them into patties about 1-inch thick.” But David and Luise simply say, “Form six patties with your hands.” Although they were tasty and colorful, dotted with grated zucchini and carrots, they didn’t hold together particularly well. (I added a whisked egg to the batter, and that helped.) That didn’t bother me much, though, because wrapped in a cabbage leaf, as they recommend, the shape is secondary to the rich flavor of the salty, fatty halloumi cheese and peppery mint leaves. You could eat these all by themselves and feel satisfied.

Another success was their Masala Dosa recipe, which cleverly shortcuts the long fermentation time required to make real dosas by using chickpea and brown rice flour to make the crêpes instead. I also made the sweet potato filling, as well as two garnishes: the Indian Mint & Coconut Raita and the Mango & Raisin Chutney. The flavor combination of all the elements together was off the charts -- and the nigella seeds in the dosa batter was the clincher. As I continued to flip through the book, seductive photos of yogurt-daubed, pillowy waffles, crisp ribbons of vegetables, and plump, pesto-slathered gnocchi convinced me to add a handful more recipes to my "Must Try" list.

Some of the recipes in Green Kitchen Travels are vegetarian stalwarts that have been covered elsewhere, or that don’t particularly need a recipe, like raw beet salad, vegetarian pho, or baked mushrooms with quinoa. Still, minor complaints aside, I wish I could eat in the style of Green Kitchen Stories every day. If I did, I suspect I’d feel as serene and beautiful as the authors look in their photos.

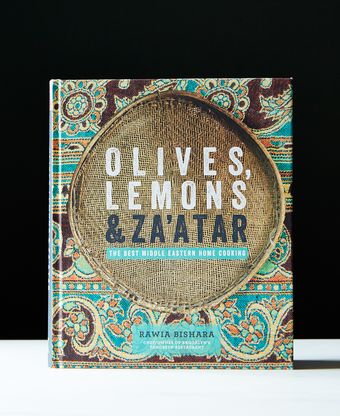

I turned next to Olives, Lemons, & Za’atar, by Rawia Bishara, the chef and owner of Tanoreen restaurant in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn. I took a friend to Tanoreen for her birthday last summer, and we enjoyed everything we ate, right down to the desserts. But as good as it was, I was less than thrilled about exploring this book; I cook, eat, write, and think about Middle Eastern food every day, and as much as I love it, I crave learning new ways of cooking. To my surprise, I found the book captivating from the first page, starting with Bishara’s story of emigrating to Brooklyn from her home in Nazareth, and being persuaded by family and friends to open a restaurant. Her childhood stories about picnicking under olive trees and waking up to homemade semolina cake with orange blossom and rose water give the book a soulful feeling.

Bishara explains that her cooking “celebrates tradition and embraces change,” and she’s not averse to putting a new twist on old recipes. Unlike many strict traditionalists in the world of Middle Eastern cuisine, she’s a creator who sees the value in innovation. That’s refreshing. A good example of this is her recipe for brussels sprouts with panko, a distinctly un-Arabic ingredient that she makes her own by seasoning with tahini and pomegranate molasses and shrouding with breadcrumbs for a crunchy finish. Her recipes for Shrimp in Garlic Sauce, Salmon in Pesto, and Leek and Potato Soup also feature ingredients she’d never had before coming to the U.S., and again, she anoints them in Tanoreen perfumes: She adds parsley, coriander, paprika, cardamom, and artichoke hearts to mouthwatering effect.

I started with dessert: the Flourless Tangerine Apricot Cake. It’s made from nut flour, with puréed fruit mixed into the batter, but for some reason it calls for a 16-inch round baking pan. (What home cook has one of those? I ended up halving the recipe and baking it in a 10-inch pan.) My husband, who is gluten-free, deemed the cake “excellent,” but it needs to be served with whipped cream -- as per Bishara’s suggestion -- because the texture is so dense. The cake also had a slightly bitter flavor, probably from stray tangerine seeds, which, as it turns out, are tricky to remove. Next time I might substitute oranges, but I’ll definitely make this fragrant cake again.

From the chapter on Mezze, I tried Hossi For Kibbeh, a spicy lamb dish that’s perfect for when it’s too cold outside to make kebab. The lamb is seasoned with allspice, cumin, black pepper, marjoram, and nutmeg -- a close take on baharat, the classic Arabic spice blend. As in many recipes in the book, the onions are a key flavor component, and here they get browned until they’re deeply-flavored and sweet. The recipe calls for Middle Eastern or Turkish chile paste as an optional ingredient. I could have made Bishara’s harissa red pepper paste from scratch, which she details in her Pantry chapter, but instead I substituted Aleppo pepper that I had on hand -- and the dish still had a nice bite and a dose of fruity fragrance. While Bishara does include a few rarefied Arabic ingredients in the book, like mastic, mahlab, sumac, citric acid, and the chile paste, the majority of the staples she calls on can be found at Whole Foods.

I also made the Chicken Pizza -- a simplified version of the traditional Palestinian dish musakhan -- with a toasted spice mix and fresh lemon juice for a tangy finish. The flavor was fabulous. (I felt the need to top it with yogurt; it must be the Persian in me.) It’s not a perfect recipe: I'm not sure why she calls for bland chicken breast. If I were to make it again I would use bone-in thighs, only one skillet (the recipe calls for two), and reduce the amount of oil -- one whole cup -- by half.

Even though I had some technical gripes with the recipes, the book opened up the fundamentals of Arabic cooking and got me excited about her new flavors. There are many more compelling dishes in Olives, Lemons, and Za’atar that I’d love to try, like the pan-fried Savory Pies known as sambosek, that Bishara suggests filling with feta and za’atar or halloumi cheese. (They're a first cousin of the samboseh I ate in southern Iran, and I want to compare the two.) And the Harira, the aromatic “soup of kings” made in Morocco during Ramadan, which calls for 26 ingredients including diced lamb, saffron and eight other spices, tomatoes, three kinds of beans, vermicelli noodles, and an egg cracked on top. These recipes aren’t even accompanied by photos -- the ingredients alone are a seduction.

Both books emphasize the importance of everyday cooking and recognize how cooking for yourself and your family is an essential part of life. And they're both wonderful. But in the end, one stands out not just as a more comprehensive cookbook, but as the culmination of a life’s work. For that reason, Olives, Lemons, & Za’atar advances.

28 Comments

http://foodmumbai.co.in