Every cookbook writer has a particular style, language, and set of staples that are so much their own—so much so that the recipes in a collection become like a close-knit group of friends, able to relate to each other in a way that can seem, at first, like shorthand to the outsider.

My small team and I are used to testing only “Ottolenghi-style” recipes—with our own language and style and staples—so we were super excited about welcoming two completely new books into the fold. We felt like a family who had scrubbed up, put on our Sunday best, and were standing in line to welcome team Mexico and team Hot Bread into our test kitchen in London’s Camden Town.

As someone who writes cookbooks myself, I know how much people put their hearts and their souls into them. Most recipes only make it into a book if the author absolutely loves and believes in them. Sending recipes out there for others to cook from is an act of faith: The recipe writer is the proud but very nervous parent standing at the school gate as their kid walks off onto the playground for the first time. “Don’t get eaten alive, little guy,” every parent is thinking. “I think you’re incredible.”

Because I believe in this lamb-to-the-wolves playground analogy, I’ve just never been one to criticize others if they’re doing something with passion, enthusiasm, and only the best of intentions. Which is why, I have to admit, this wasn’t as much fun as I thought it was going to be: When something didn’t work out for me in either of the two books, it all felt rather churlish to be criticizing something you know to be so personal and winning to the author.

Disclaimers aside, there was a job to do—and a winner to find—so I pulled up my proverbial socks, tied my apron strings, and got going.

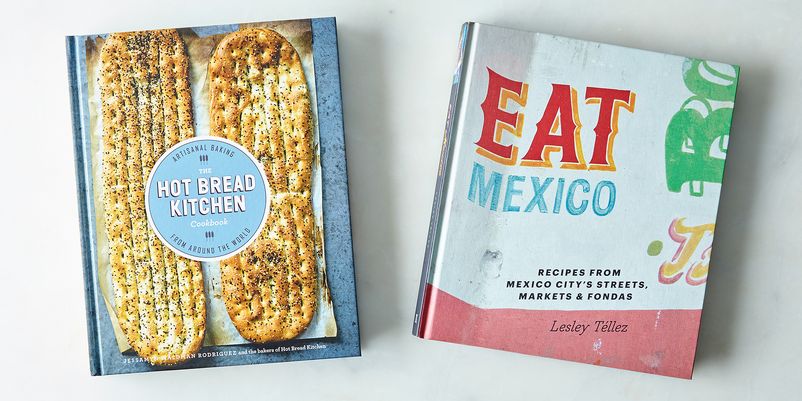

Lesley Téllez’s Eat Mexico and Jessamyn Waldman Rodriguez’s The Hot Bread Kitchen Cookbook are two very different books. The first is very much a personal odyssey—it’s Lesley’s journey of discovering the food she found and fell for in Mexico City when she moved there with her husband. The second is the journey of a collective: a group of bakers from around the world working together in a small bakery with a big mission.

With Téllez’s book, I thought it would be interesting to do a couple of things that were new to me plus a couple of recipes I was more familiar with in order to see how they're handled in another cook's kitchen.

The need for several of the recipes to start with 36 dried corn husks or cactus paddles ruled out a fair few options for me, but there were some Huevos Montuleños— eggs with tortillas, ham, and peas—that I liked the look of and thought would hit the brunch spot pretty well. There were a couple of elements that had to be made in advance but were quick and easy to do: the refried beans and then a tomato-based ranchera sauce. The sauce is a nice thing to have on hand and is easy to store in the fridge or freezer—this recommendation might have been a nice one to for Téllez make. A lot of cooks would do this anyway, but it’s useful, I think, to have these little tips and tricks dotted about a book. Another one? When peeling such a large batch of tomatoes, as you do for the ranchera sauce, mark the base of the tomato with a cross before it gets covered in hot water. It helps enormously when peeling them. Again, this is something a lot of home cooks would do instinctively, but, for those who don’t know, it’s a real nugget of information to pass on.

The sauce tasted fine; I added a pinch of sugar to mine, as tomatoes are not at their sweetest this time of the year, and I was tempted to add a bit of smoked paprika or some Urfa chile flakes to give it a bit more oomph, but it served its purpose. Everything else was all set to go, and then it was a case of just putting the dish together with the beans, the fried egg, the peas, ham, cheese, and so forth, layered between the corn tortillas. The result was—and I’m aware that I’m repeating words here—fine: Serve it to a group of student friends or anyone with a hangover and you’d be their best friend, but I would have liked a few recommendations for things that could have worked on top as extras if you wanted to play around, in addition to the fried plantains she mentions. Some chopped spring onions would have been great, for example, as would have some fresh coriander leaves. Slices of avocado, a drizzle of tahini. Any (or all) of these would have taken the dish to the next level for me.

Next up was Eat Mexico’s Stewed Swiss Chard, which I thought would go well with the Amaranth and Pumpkin Seed-Crusted Chicken with Creamy Pomegranate Dipping Sauce. Amaranth is a relatively new addition to my kitchen, and I’m always interested to explore more ways to cook with pomegranates. The chard was nice in the way that chard is nice, but I’m not sure it was much more than the sum of its parts. The dish was sold in the intro as having a creaminess to it with the addition of chickpeas, but I didn’t find this happened with the canned chickpeas I used. I would have liked a lot more onion—I’d cook it for longer to get a real sweetness through the dish—and my garlic nearly burned as it was added at the same time as the onion.

The difference between one large bunch of chard and another is huge, which is why I’m a real stickler for more precise weight measurements: I’d prefer for them to be there for the reader to ignore if they wish, rather than not being there in the first place. Some of the vagueness in the chard recipe's ingredient list is helped marginally by the photo alongside; we’re not told what size the tomatoes or onions should be chopped, but we can infer from the photo.

The chicken was interesting enough: comforting, easy, something that young kids would like. I really liked the taste of the pomegranate sauce, but its deep purple color really didn’t look great. A few freshly chopped green herbs—some coriander or parsley—would be a quick way to improve its appearance.

The Hot Bread Kitchen Cookbook made me want get into the kitchen and get cooking straight away! There were just so many things I wanted to try, to make, to eat at home. At the same time as having a really clear focus—the book is full of recipes from women from all over the world who have come together to work at the bakery in exchange for training and education—it is absolutely rammed with all sorts of other information. We get baking tips and tricks, in page-long instructions and little quick-fire tidbits both; we get baker profiles; we get business advice for those wanting to set up their own company, and snippets on what the author has learned about juggling her career and family life. All of these weave together to give the book such a strong identity; it’s the sort of volume you want to have in both the kitchen and in bed, simply to read for pleasure at night.

I could have cooked every recipe, but settled on three for a good morning’s work. I’ve been trying to crack injera bread, the deliciously sour wheat and teff flour flatbread common in Ethiopia, for a while now, so I started there. Rodriguez is not shy about straying from strict traditions, which I like: The addition of butter to the pan before the flatbread is cooked is not conventional, for example, but it yields delicious results.

The recipe was very clear—I really liked the bold capitals used for the ingredients, which stood out without feeling as though you’re being shouted at. Not having to convert the cup measures to grams myself was also something I really appreciated. And the recipe transports you, too, by means of suggesting Ethiopian stews and sides the bread goes well with, plus a profile of Hiyaw Gebreyohannes, a HBK success story who went on to found The Taste of Ethiopia. With one stack of injera, you really feel like you are getting a little slice of its country of origin.

Next up was M’smen, the Moroccan flatbread: They’re not the easiest to make, but the clear instructions and photos of the various cooking stages guided me through.

From the flat to the risen, their Traditional Challah was the next chosen one. We had some initial confusion over our conversion from kosher salt to the sea salt flakes we were using—we doubled it rather than halved it—so the first batch didn’t rise enough and was too salty. We got it right for batch number two, which came out of the oven in its golden, glowing, shiny glory.

Instructions for this type of involved bread are never going to be the most straightforward to read, but the photos which go alongside are really helpful and reassuring. Having made the one master recipe, it was also brilliant to know that the door was open to so many other variations with the off-shoot recipes that followed.

Eat Mexico is a nice book. Mexican food still suffers very much from being homogenized by the uninitiated—those who think it’s all "Tex-mex"—so anyone who does anything to shake this assumption, Téllez included, is worth checking out. I’d give this to a friend who was off to uni.

But I'll be pressing The Hot Bread Kitchen Cookbook into the hands of many. It manages to pull off the difficult balance between both a story and a guide: It details the passion project of a small group of amazing individuals while being a practiful, useful, down-to-earth book for the home cook who really just wants to make great bread. There are just so many ways to get your work surface covered in flour—tortillas, bialys, chapatis, lavash, sweet loaves like banana bread—I can’t wait to keep going. The Hot Bread Kitchen Cookook is the book to make both your bread and your spirits rise—and it’s certainly the winner of this cook-off.

38 Comments

Yum. Thanks for a wonderfully tested and (unsurprisingly) thorough review.

Will continue to buy Hot Bread Kitchen bread for now, since I am lucky to live in New York.