(My 30-year obsession: Elizabeth David Penguin paperbacks, published in the 1950s through the early 1970s. They smell like oxidized wood and vanilla. Caramel-colored penumbras seep around the margins, staining blocks of text. The pages shed like quills if you don’t pry the covers open gingerly, with just the right degree of tension—no bending. A necessary strictness, out of respect, rules the way you approach them.)

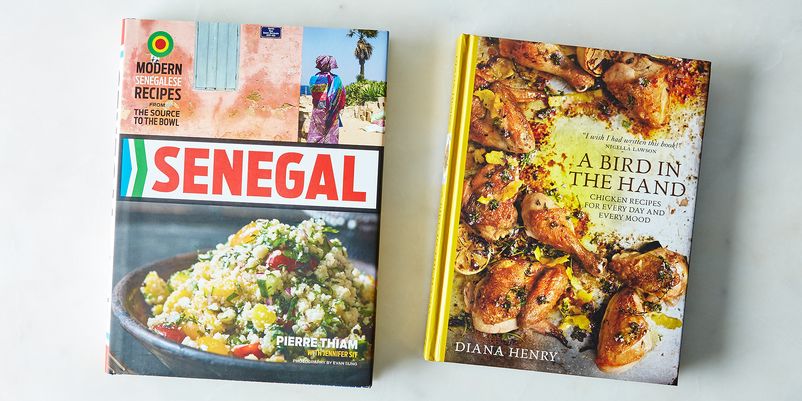

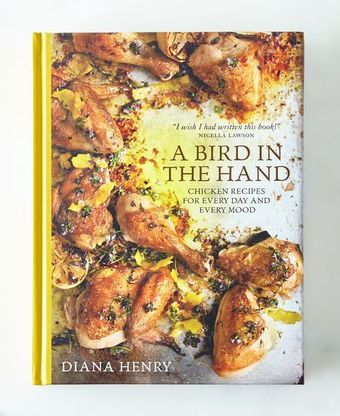

A bubblewrap-padded envelope arrives. Ah! My first Piglet book. It’s Diana Henry’s A Bird In the Hand: Chicken Recipes for Every Day and Mood—every recipe is for chicken. Henry is an Irish writer; the bio bit in the back of her book says she has a weekly column in The Sunday Telegraph. I picture newspaper broadsheets open on breakfast tables; toast and jam. Cloth napkins. A Bird In the Hand is not huge or bombastic-looking. You could take it with you to Whole Foods and not struggle with the bulk or feel ridiculous. The cover seems one you could daub with a sponge without hurting anything, though—seriously—who ever wipes down a book?

(This is my Elizabeth David paperback collection: Summer Cooking (1955); French Provincial Cooking (1960); Spices, Salts, and Aromatics in the English Kitchen (1970); three or four more. It’s a faded stack. I assembled it shadowing bookshops in San Francisco and Berkeley, across a year I can still remember the taste of.)

“I wish I had written this book!” Nigella’s blurb is literally on the front cover, above the title. Yes: Diana and Nigella seem part of some urbane and decorously pleasure-loving circle of British food writers. They probably pretend to be amusingly jealous of each other, waving at one another from tables at smart London restaurants. They know the world. Henry’s chicken recipes show an easy-going range of reference, from Spain and France to Korea, Japan, Brazil. North Africa.

If A Bird In the Hand were an American book, there’d be some crushingly, hyperbolically definitive formula for the ultimate roast chicken, but this is not an American book. “It sounds like a cop-out,” Henry writes, “but what I found is that there is no ‘right’ way to roast a chicken.” On the same page: “So much about cooking is to do with your mood, what you can manage, and what’s available.”

(David, who died in 1992, is the fiercest, most introspective, and caustically intelligent food writer England ever reared. Her writing taught me the importance of evoking place in my own. Her recipes—sketchy; almost, in her early books, impressionistic—conjured moods. Unlike the precise recipe authors who were her contemporaries in America (Julia Child, for instance, tells you how many fractions of teaspoons of pepper to add), David favored loose instructions that trusted readers to rely on their own judgment, even their imaginations. This was partly the times, and the convention of British cookbooks, partly David’s temperament. Maybe she knew some readers would scan her recipes purely as entertainment. She certainly wanted them to know the world better.)

I cook Chicken Piri Piri, which takes two days—a marinating of jointed legs and thighs overnight in a roasted pepper sauce, then broiling. They’re good: blackened skin, very slight amount of heat, whine of vinegar. Then it’s Pomegranate and Honey-Glazed Chicken Skewers, squarish pieces of thigh meat left to soak with Lebanese pomegranate molasses (had to stop at the Middle Eastern grocery for that), olive oil, honey, and spices, the next night threaded on skewers and grilled. Chicken with Prunes in Red Wine is a Sunday braise that yields tasty juices. These are all dishes with the right scale for a life of work obligations and house clutter you struggle to get an upper hand with. They’re smart, built around simple processes, enhanced by little glory touches and modestly bright flavors. They’re practical—imaginative in a way that doesn’t tax you.

Book two arrives in cardboard I have to cut open with an angled scissor: Senegal by Pierre Thiam (with Jennifer Sit). "Modern Senegalese Recipes," the subtitle goes, "From the Source to the Bowl." Blurbs by Robert Sietsema and Akon (that Akon?), and an intro by Jessica B. Harris. It’s handsome: large, heavy-papered, densely illustrated with photos by Evan Sung. A travel book, too, and a plea for understanding West Africa’s food and traditions—its spirit.

“I hope,” Thiam says in the preface, “that the readers of this book come away understanding the depth of this cooking and its place in the world so that it is no longer unfathomable, alien, misunderstood—not just forgotten, but unseen.” That’s beautiful.

(David was writing her first recipe collection, A Book of Mediterranean Food, at the end of the 1940s, when British readers under a heavy regime of post-war rationing would have struggled to find a lemon or olive oil, much less a couple of pounds of beef to braise en daube. In the context of its time, it was less a practical manual than a manifesto for pursuing vividness and pleasure and the limits of your own intelligence, written, David later revealed, from a sense of rage at British complacency, mute acceptance of a dreary imposed reality. A Book of Mediterranean Food reaches and aspires. It subverts. This is the test of a cookbook for me: Does it expand my experience of the world, even in small but indelible ways? Does it play on my imagination, urging me to complete a gesture the author’s begun? Does it persuade through seduction?)

Thiam is a chef who lives in New York City, grew up in Senegal, and owned a couple of Brooklyn restaurants, Yolele and Le Grand Dakar, now closed. He’s handsome on page 210, smiling, in good glasses and the simple cotton clothes a fashion site would call “smart menswear basics.” You sense his confidence. “He looks like a J. Crew model,” a friend says, intending it as a compliment.

I love Thiam’s exposition of Senegalese eating culture—the ingredients and flavor categories that built it, the geographic spread of tastes and dishes. More than anything, I love reading about teranga (“hospitality” in Senegal’s dominant language, Wolof). It’s a style of eating from a big central serving bowl with right hands, everybody taking what’s offered, dipping in for fonio or another grain.

I’m fascinated by fonio, a species of millet with extremely small grains. Taking Thiam up on the book’s promise of modern Senegalese recipes, I make Moringa Veggie Burgers—patties of cooked fonio mixed into mashed yucca with spinach (Thiam’s suggested substitute for moringa leaves, which I can’t find). They’re tricky to fry, and the recipe’s too salty, though the topping of Yassa Onions (caramelized, peppery) is good. So is Tamarind Kani Sauce, a tomatoey condiment throbbing with habanero heat. Tabbouleh-like Mango Fonio Salad is nice, except it has way too much dressing (a whole cup of olive oil in a recipe serving four!). Coconut-Lime-Palm Ice Cream looks amazing—a vivid burnt orange from the red palm oil emulsified into the custard base—but the flavor’s flat, the eau de cologne taste of orange flower water seeping everywhere. Senegal walks confidently as travelogue, an introduction to an intriguing and strangely familiar food culture, but as a cookbook it wobbles.

Henry knows how to satisfy the raw need to get something on the table while slapping gently against your imagination with flavors, cuisines, and ingredients that feel lively but non-dogmatic, leave you curious or wanting more. Senegal is an intriguing dive but frustrating—Thiam is way better at crafting an argument through words and pictures than with recipes. And in any good cookbook, ultimately, it’s the recipes that carry the narrative. A Bird In the Hand is the book I know I’ll prop open on the kitchen counter, conspiring with Henry’s taste, intellect, and experience, almost like we’re acquaintances, flicking an admiring look at each other through the pages.

35 Comments

A book of chicken recipes? Not for me. I could have written that!

As for chicken recipes! I've cooked a chicken or two a week for us at home for decades and thought there'd be no way I'd buy that book. But sometimes Piglet magic happens. At the very least, it will remind me not to ignore Elizabeth David just because I have to open them so gingerly.