It’s a little on the nose, but here we are: I’m writing this in November, after the election, while I and a good portion of the country’s population is feeling, well, weird. Here we have, going head to head, two books that might very well represent our American divides: Koreatown, about immigrant bastions that dot the U.S., and Victuals, about the lesser-known cuisine of Appalachia. Here are books about populations that you might not know much about, depending on what particular corner of the country you call home. Koreatowns exist in bigger cities—Los Angeles, New York, Washington, D.C.—whereas the subjects of Ronni Lundy’s Victuals exist in places less densely populated: Kentucky, Ohio, Georgia, Tennessee, West Virginia, North Carolina. Chances are, you’re familiar with one of these populaces, and maybe only passingly familiar with the other.

Were we to judge these books by their covers—and don’t worry, we aren’t—we’d register their differences immediately: Victuals features a lesson in pronunciation (it’s pronounced VIDLS) and a blurb from Emmylou Harris, and looks serious, almost text-bookily austere; Koreatown's cover is an array of Korean banchan with letters styled over, like pop art. But before you dismiss one or the other as not your cup of tea, I promise there’s more to both than meet the eye, and more resemblances too. As it turns out, they’re both passionate portrayals of populations within our country. Not only are they windows into worlds, they’re invitations in.

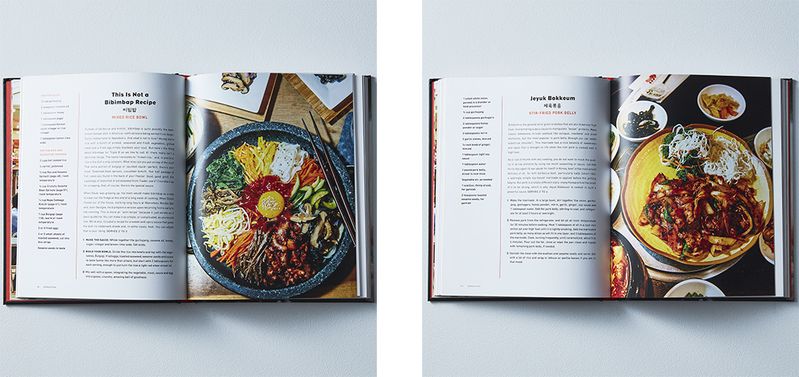

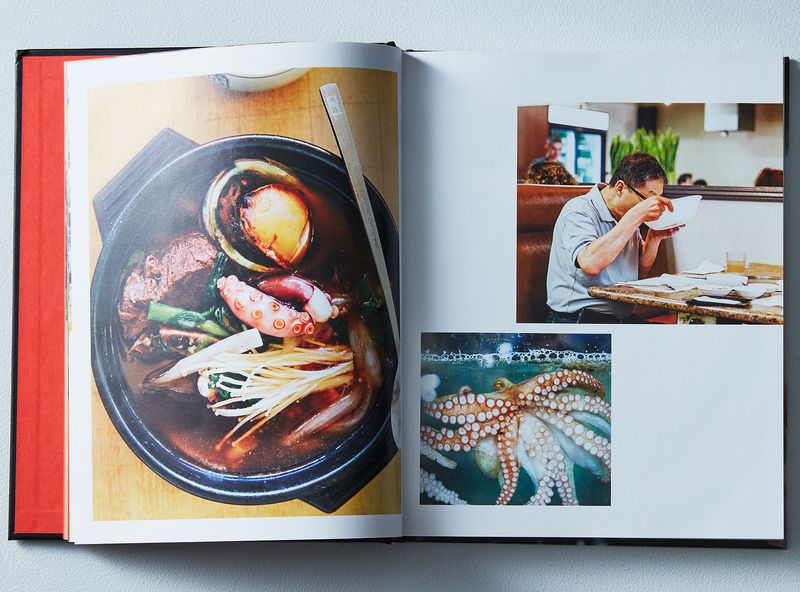

Koreatown, coauthored by writer/editor Matt Rodbard and chef Deuki Hong, is easy to dive directly into: the writing and aesthetic are punchy, breezy, and in-the-know. Documentary-style photographs transport us to Korean restaurant exteriors, bubbling pots of orange stews, grocery aisles packed with vegetables, glistening meat on grills. Though the book purports to be for everyone—its tone is patient and expositional—it does seem to have an apparent audience: The humor’s for the dude who laughed at all the jokes in The Martian, who’s eaten kimchi at least once before, and who knows who Eric Ripert is, and cares to read a Q&A with him on the subject of Korean food. Having grown up in a town with an H Mart (shout-out to Diamond Bar, California!), and edited a magazine founded by a Korean-American chef (*cough* David Chang), this is a world that’s familiar to me: I’m not Korean, but I’ve eaten in Koreatowns, I’ve eaten in Korea, and I know Koreans. I shop regularly at the Korean grocery because I’m a fan of the dumplings and rubber gloves. Still, the book is quietly educational. Never abrasive with facts, it’s unobtrusively informative, with something for everyone—newbies and veterans alike.

Koreatown is first and foremost a love letter, not an anthropology lesson. Among the book’s chief strengths is its unflagging and genuine enthusiasm: These guys LOVE Korean food, and you cannot help but be swept up in their fervor. Everything looks mouth-watering and evocative; whether bulgogi or “fish cake soup,” each recipe is presented with equal and impressive aplomb, made to sound like THE MOST IRRESISTIBLE FOOD ON EARTH, and also made wholly accessible. I’m totally susceptible. I’m unable to read the book without frantically flagging recipes with little Post-It notes. It’s fittingly reflective of Korean cuisine—this array of recipes like banchan packed across a table. One night I try the Jeyuk Bokkeum (stir-fried pork belly), Miyeokguk (birthday seaweed soup), and Kongnamul Muchin (crunchy sesame bean sprouts). The pork belly is doused in a cocktail of sauces far greater than the sum of their parts, fiery and savory, cutting the richness of the pork fat. (Those packs of sliced belly you find at the Korean market would have been perfect for this purpose, but I bought a pound of pork belly from a non-Korean grocery store, sliced it as thinly as I could, and still found the dish delicious.) The seaweed soup was solid—worth the teasing I endured from the butcher for buying a quarter pound of brisket—and so were the bean sprouts, unflashy but addictive. The bulgogi, which marinated in a Ziploc bag for 24 hours, was also a winner. (Though I chickened out on the two tablespoons of black pepper the recipe called for, and put in, like, one and a half teaspoons instead. It was still as peppery as beef jerky—which is to say, peppery enough for me). I mixed the bulgogi into a bibimbap using the loose guidelines of “This is not a bibimbap recipe,” Rodbard and Hong’s bibimbap insistently-non-recipe formula. The bibimbap sauce called for a tablespoon of Sprite, and I felt like I was doing a magic trick. Of course it was amazing. For days, I spooned it over everything.

I’d make a connection between Korean food and the food in Victuals, but as it happens, I don’t have to: Chef Sean Brock’s already made it for me. “For some strange reason the ritual of eating Korean food is very similar to the way I grew up eating in the Appalachian Mountains,” he’s quoted as saying in Koreatown, where he gives a recipe for a Korean pancake. “Every time I eat at a Korean restaurant, I am reminded of my childhood, because we, too, had huge spreads of food that included lots of pickled, salted and soured condiments.” Like Koreatown, Victuals gives a look into a diaspora: Appalachia.

Author Ronni Lundy was born in 1949 in Corbin, Kentucky, where she also grew up; this book, her fourth, is dense with histories both personal and regional, and also—via interviews and investigation—a hopeful look into the region’s future. Not long ago, Lundy was struck by the disconnect between her experience growing up and the way Hollywood portrayed her people in "Deliverance," say, or "The Beverly Hillbillies." Via this cookbook, through a focus on food, Lundy sets out to right so many deep-seated misunderstandings: Her quest takes her over 4,000 miles in a “reliable but rough-countenanced” Chevy Astro van. Along the way she talks to cooks, farmers, and museum docents. The enthusiasm is quieter than Koreatown’s, but it’s no less persuasive. The photos are abundant, black-and-white landscapes alongside colorful vegetables, a tractor here and some chickens there. It’s a book that considers the land and region so reverently you can’t help but be swept up in it—transported to a rocking chair on a porch, stringing beans; living a wholly different childhood, tying a June bug to a string.

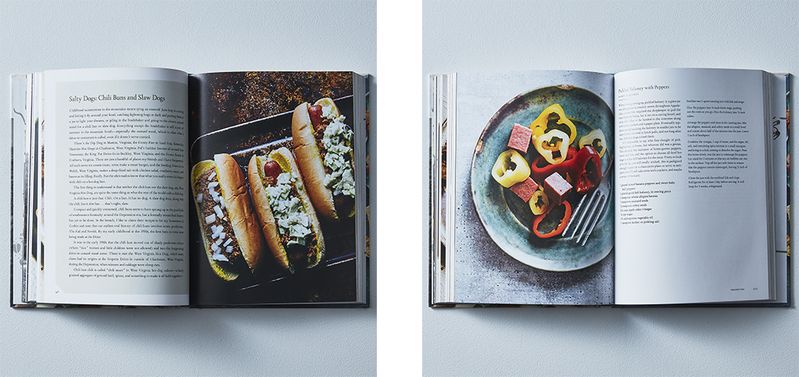

The recipes are divided into ingredients: a chapter on apples, another on beans, another on corn. There’s a chapter on animal husbandry. I read, enthralled, a section called “Messing with Greens,” about the different ways to cook wild greens picked in the spring. You “kill” greens! You pick a “mess”! The words are endlessly delightful (“Cheese nabs” anyone?) and it’s clear that Lundy delights in them too. Her voice is assured but never pedantic; her enthusiasm is contagious. As for the recipes themselves, they are across-the-board simple—dependable as her Chevy Astro. Victual’s recipe for colcannon, that traditionally Irish concoction of cabbage over mashed potatoes, was ribbons of kale and cabbage draped over heavily creamed mashed potatoes, pointy with crisped bacon. A cream-dressed dish of peas and radishes was deceptively light and fresh. The cucumber salad, thin slices of cucumber in buttermilk dressing, was tart and complex for its surprising ease—it’s something I’d make again in a heartbeat. And I wholeheartedly enjoyed my first-ever “slaw dog”: a hot dog piled with a simple chili made with a cup of flat beer and crushed saltines, topped with a mayonnaise slaw. The 1950s have come and gone and I missed my chance to eat chili buns and slaw dogs in the pool rooms of southwestern Kentucky (I would have also had to be a man), so it felt special to get to eat one in my home in San Francisco.

Cookbooks are ambitious, impossible things—imperfect by necessity. Koreatown and Victuals are both very, very good cookbooks. I’m only including nitpicks here under judging duress. Victuals occasionally calls for ingredients that are hard to find, without any substitutes offered. The unapologetic recipe for “Redbud Caper Deviled Eggs” calls for “capers” made from the “unopened buds from a redbud tree,” which… what? It was kind of novel, the inability to find an ingredient in the Bay Area. It was also a chance to google “redbud trees” and scroll, mesmerized, through the many images. Koreatown was better at explaining ingredients and offering alternatives to ingredients we might not easily hunt down. Less successful are the interviews titled “Eating Koreatown,” which do a disservice, I think, to all the nuanced groundwork Rodbard and Hong lay elsewhere in the book. We hear from semi-famous people, like actor Andy Milonakis (“I still need to get schooled in the names of dishes, but I know what I like”) and writer Adam Johnson, who wrote The Orphan Master’s Son, a good novel set in North Korea, yet somewhat reductively sums up that when you “taste Korean food, you can taste the resilience of the people.” In Victuals, the interviews went the opposite direction: From time to time they were puffy, going on longer than they should have. In recipes, though, that same tendency to linger turns out to be a boon: Though both books contain well written, easy-to-execute recipes, Victuals does a better job of answering questions that might arise, because Lundy just hangs out with us a little longer.

In the end, these quibbles are small, and both Koreatown and Victuals are accomplishments, deserving of your time and shelf space. Both reveal nuances in cuisines that are otherwise easy to miss: Korean food isn’t just about fiery spice; there’s more to Appalachia than cornbread. But I’m supposed to pick a winner, so let’s see. I’m a novelist and a cookbook author, and books are many things to me: They’re about escapism and education. They’re an exercise in empathy and they’re a window into other worlds; they’re a way to shake ourselves out of sleepwalking, out of close-mindedness. They’re a way to live other lives drastically different from our own—to imagine ourselves in a pool hall in Kentucky, or belting a karaoke song after one too many sojus. Taken to these myriad and difficult tasks, both Koreatown and Victuals succeed. But maybe Victuals, in its diligence and thoroughness, succeeds just a little bit more. Anyway, today I made myself leftovers—I piled kimchi high on a slaw dog—and it was actually really good. They got along perfectly.

64 Comments

You really did capture the essence of this book. And at a time when the country seems so confused, you struck a true chord writing a book that focuses on a part of our population that's exotic and often misunderstood.