I haven’t used cookbooks regularly in years. This is not to say that I’m a bad or incurious cook; I have a roster of 15 to 20 mostly-memorized recipes (templates, really) that I cycle through at home—generally ones that take an hour or less (I have a 4-year-old).

It’s also not to say I don’t like cookbooks—I love them! It’s how I taught myself how to cook, years ago. And, at my desk, I have a towering stack of coffee table cookbooks—mostly by chefs at big-name restaurants—that I enjoy flipping through, admiring the pictures and thinking how I’d never, ever cook any of the 25-ingredient, 15-step recipes within.

And yet, here I am with two cookbooks to evaluate. Luckily (or perhaps unluckily) for me, they are both excellent. That is partly because they each have something that I deeply value in a cookbook: a sense of place.

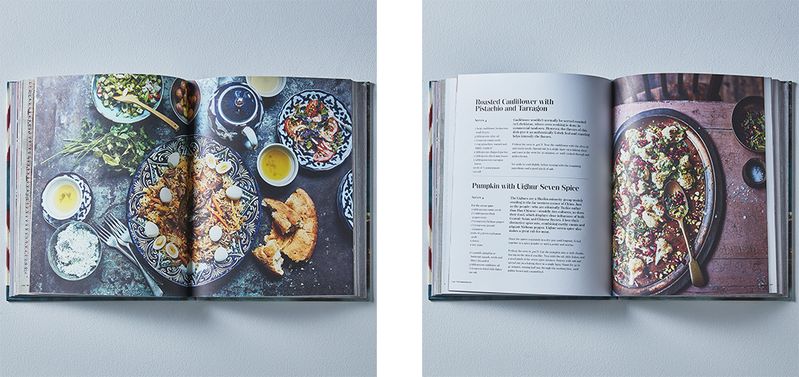

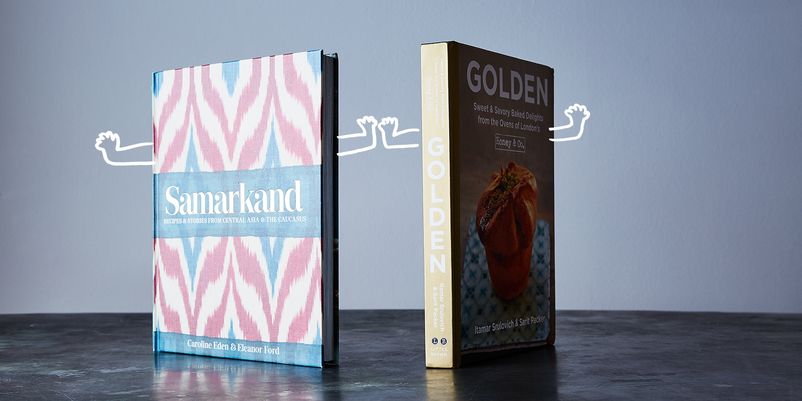

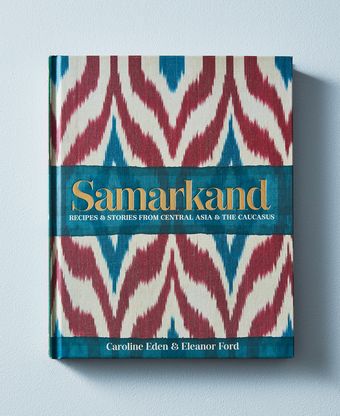

One wears that quality on its sleeve (and title page): Samarkand: Recipes & Stories From Central Asia & the Caucasus, by Caroline Eden and Eleanor Ford. Samarkand, for the uninitiated, is a city in modern-day Uzbekistan, but centuries ago was at the midpoint of the Silk Road, the essential trading route between Xi’an, in China, and Istanbul. Just as that city was the meeting point of a massive swath of Asia, the book includes traditional recipes from Georgia, Armenia, and throughout the ‘stans—an area spanning thousands of miles.

Despite that sprawl, a handful of ingredients pop up over and over: tarragon and dill, cumin and coriander, pomegranate seeds and dried fruits, mulberries and barberries. (Good luck finding those last two, and you’re not offered a substitution.) And meat—lots of it, mostly beef, chicken, and lamb. There’s not a lot here for vegetarians (or pescatarians, for that matter), though vegetables do shine in a number of dishes.

The writing throughout, both the essays by Eden and the recipes by Ford, is studied but accessible. I knew next to nothing about Central Asia going in to Samarkand, and I’m so pleased to have changed that. Some essays delve into regions and cultures, like the one on the Mountain Jews of Azerbaijan, who mostly live in Gyrmyzy Gasaba, perhaps the only all-Jewish town outside of Israel, Eden tells us. (I’ve still yet to make the “Mountain Jew Omelet,” which features chestnuts and poached chicken. It’s one of a number of wonderfully named recipes in the book; see also: Buttered Rice under a Shah's Crown, and Thunderstone Lamp Chops With Sour Cherry Sauce.)

Others focus on a dish, like non bread—similar to Indian naan, but puffier, and stamped with a chekich, a metal-and-wood device that’s both decorative (each has an elaborate geometric pattern) and functional (it allows steam to escape and pushes down the middle of the bread, giving the final product its bialy-on-steroids look).

Another hones in on plovs and pilafs, those ubiquitous steamed rice dishes, and there are versions from Bukhara (another Jewish enclave, in Uzbekistan), Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan. I chose to make the Samarkand plov (when in Samarkand, right?), which features diced beef and thick matchsticks of carrots (orange and yellow are requested in the recipe). The dish is made in layers: the beef, jacked up with onions and bay leaves, then the carrots and spices, and then the rice. It all cooks in a big, heavy pot (you are advised to poke holes in the rice with the handle of a wooden spoon to help steam escape), then is served on a platter in reverse order. It’s a gorgeous, buttery, ridiculously fragrant dish.

Another night, I held a Samarkand dinner party (achievable, for me, with the chopping assistance of a friend). We started with tarragon soda, which combines that licorice-y herb (it competes with dill—to which I have an aversion, I’m sorry to say—as the book’s most ubiquitous) with sugar and lime. It’s delightful, and I’m sure would benefit from the optional addition of vodka.

Then, salt-massaged cabbage: Thin shreds of the cruciferous vegetable, as well as carrot, bean sprouts, and chile, are rubbed with salt and sugar until they give up their liquid. The liquid is discarded, the whole thing is rinsed and drained, and then it’s lightly dressed with vinegar and herbs. I actually found the result to be a little bland—a more assertive dressing would have been welcome. (I also substituted a jalapeño for the red chile recommended, which was a mistake; the salad would have benefited from the brightness of the hotter pepper.)

An Armenian soup of dried apricots and lentils followed, redolent with cumin and thyme. The whole thing is half-blitzed with an immersion blender for a pleasantly pulpy texture. Thinking that there’s no such thing as too much dried fruit, I paired that with a chicken, prune, and potato hotpot, which features both dried apricots and prunes, as well as apples, allspice, tarragon, and pistachios. It elicited moans of pleasure from the table.

Elsewhere in the book, I was seduced by a photo of a gorgeously shellacked Georgian chicken with walnut sauce. (The photography, both of the dishes and shots from around the region, is uniformly excellent.) I’m predicting that the chicken recipe will become a go-to for me: simply seasoned with coriander and cayenne, then rubbed with olive oil and drizzled with lemon. (I have one nit-pick, though: The olive oil and lemon should go on first, not the spices; I found that the former washed off the latter.) The chicken is paired with garo, a sauce of walnut, garlic, cilantro, coriander, turmeric, and fenugreek (the last, a bitter and nutty spice, required some calls around to specialty stores; note that it is unrelated to fennel seed, which does not qualify as a substitute). The sauce, which comes out a pale but pleasant green-yellow, went wonderfully with the chicken.

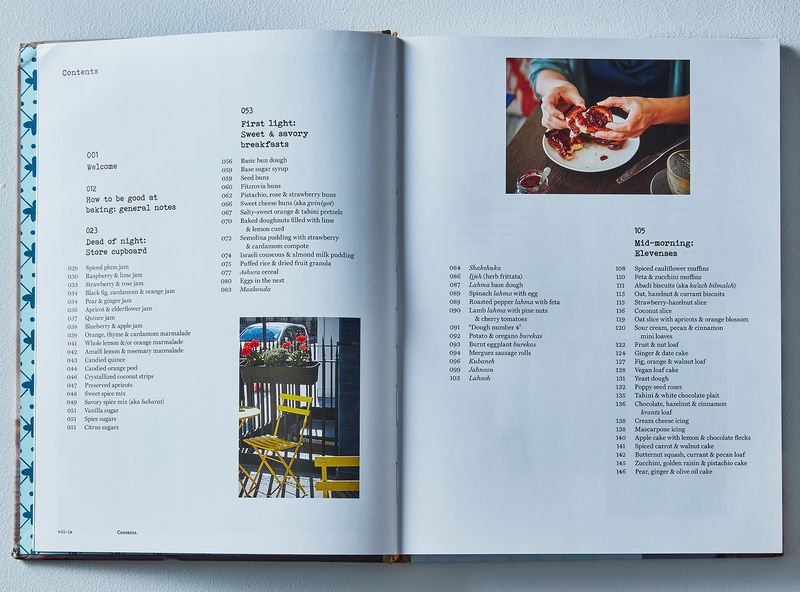

My favorite recipe from the book is one of its most simple: roasted cauliflower with pistachio and tarragon. The cauliflower (I used an in-season orange varietal) is roasted with cumin seeds, then tossed with crushed pistachios, parsley, tarragon, mint, and pomegranate seeds. Intense in both flavor and color, it has already become my default cauliflower preparation.

The sense of place that Samarkand conveys is full-on macro. The focus of Golden: Sweet & Savory Baked Delights from the Ovens of London’s Honey & Co. is both macro and micro. It’s written by Itamar Srulovich and Sarit Packer, who met a decade ago in an Israeli restaurant kitchen. Their cooking—and the food in Golden—includes influences that have been absorbed via family and immigration in their native Israel: Turkey, Morocco, Tunisia, Yemen, and so forth.

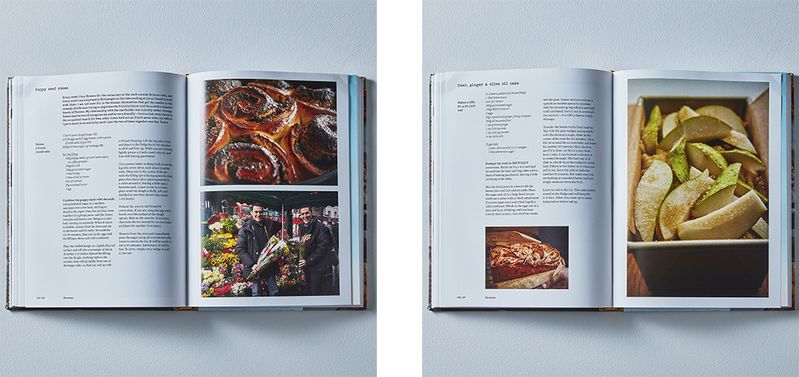

But the book also imparts a more modest sense of place: Namely, Honey & Co, the sliver of a café that Srulovich and Packer run in London. (Golden is a follow-up to a much-praised cookbook of that café's name.) It does so through photography (there are plenty of lovely, glowy shots of purveyors and cooks, almost always caught in frozen but genuine-looking smiles), but mainly through Srulovich and Packer’s voices, which are friendly and playful in a way that is frankly hard to pull off in a cookbook. Recipe headnotes are sometimes little stories about their cafe (“We met Tim sitting at one of our outdoor tables on a sunny morning…”) or cute notes to each other (“They say real men don’t eat quiche but this does not apply to Itamar…”).

The book is cleverly divided into sections that reflect the lives of two people who run an English cafe: “Dead of night: Store cupboard,” “First light: Sweet & savory breakfasts,” “Mid-morning: Elevenses.” There are also much-appreciated sections with names like “How to be good at baking” and “General baking guidelines.”

Why much-appreciated? That’s my second confession: I’m not much of a baker. I just don’t find it as pleasurable as cooking, perhaps because of the added need for precision, perhaps because if forced to decide, I’d rather expend my calories on savory than sweet. Golden, though, features both and, as noted, is a pretty good entry-point.

Indeed, Golden took an early lead in the competition thanks to a cake—a pear, ginger and olive oil number that I chose for its in-season appeal. I’m here to tell you that it may be the ultimate autumnal dessert: sweetened by pear and sugar, but with the bite of ginger (both ground and crystallized), made perfectly moist by the olive oil. And besides some intensive prep work (dicing crystallized ginger is hard!), it’s an easy recipe.

An aside, but not an inconsequential one: Neither of these books includes time estimates in their recipes. Is that not a thing anymore? If so, it’s a shame. They are, to state what should be obvious, very helpful. Especially if there is a 4-year-old waiting for the cookies you are baking together. Golden does offer both metric and imperial weights in recipes, though, which I was glad for.

I had less success with the su boregi (“aka a bake named Sue or Turkish lasagna”), a dish from Istanbul. It layers pastry, a seasoned egg and cream mixture, and globs of ricotta and feta. It looked so appealing but took me 20 extra minutes to brown the top, which dried it out; it was also flabby and flat.

Guess what? All of that was my fault. I used a 12-inch skillet instead of an 8-inch. I only realized it while layering. I know, I know. I should have paid more attention to “general baking guidelines,” especially the first sentence: “I have said this before, but it is worth saying again—always read the entire recipe before starting.” In the end, the dish was still reasonably tasty.

I also had some trouble with the chocolate and pistachio cookies, but I’m fairly sure that one wasn’t my fault—I followed this recipe to the letter. I ran into trouble when I was instructed to rest the chocolate batter in a cool place or the fridge before coating in the crushed pistachios. I put it in the fridge for the advised 10 to 15 minutes, then another 10 minutes in the freezer, but still found it unworkably gooey. I ended up getting the pistachios on, but after cooking, half of the resulting cookies fell apart. The remaining half (and other pieces I salvaged) were deeply rich and tasty.

But Golden made a comeback with two dishes that used the book’s simple, lightly sweetened “basic bun dough” recipe as their base. First was the pistachio, rose, and strawberry bun, a rustic beauty that graces the book’s cover. I skipped making the strawberry and rose jam (mainly because I couldn’t find rose petals, and I found a lovely substitute at our local Romanian grocery store), but was enchanted by the pistachio cream that it layers over—a sweet and slightly nutty delight. The buns plumped up in muffin tins—perhaps unsurprisingly, my versions didn’t come out as pretty as the cover model, but they were plenty tasty.

Then there were the sweet cheese buns, or gviniyot. The filling combines ricotta, orange zest, and vanilla to a delightfully fragrant effect. I failed to pinch the bun dough effectively, so the filling oozed out more than it was supposed to. No matter. I glazed the whole thing in a perfumey mix of sugar syrup and orange blossom water. The result was pleasing both warm and at room temperature.

I was charmed by the writing and the recipes in Golden. But Samarkand opened me up to a new culinary world. It’s tough to compete with that.

42 Comments

It was nerve wracking to be up against Golden. Itamar and Sarit are not only shining lights in London’s flourishing Middle Eastern food scene, but they are lovely people. They have been very generous in their support of Caroline, me and our book. Only a few weeks ago, Itamar cooked my Samarkand Plov for us all to eat together - it has never tasted better.

As for readying a chicken for roasting, this is clearly a debate that needs to happen! I have always found rubbing the spices and seasoning in first imparts the best flavour. Oil then helps the skin crisp and protects the spices from being washed off by the final spritz of lemon. I would be interested to hear others’ thoughts.

That's a debate that needs to happen.