Living and cooking in New York City, where countertop space is at a premium, one doesn’t acquire too much dedicated kitchen equipment. I have always viewed a stand mixer as a suburban indulgence (a comically tiny version of those industrial-size dough mixers in pizza kitchens), and besides, who hasn’t made a pie crust from scratch only to realize the best substitute for a rolling pin is an unopened bottle of red wine? But the exceptions New Yorkers do make to these restrictions are reflective of their individual cooking styles (mine are a Vitamix, a Baratza coffee grinder, and an ice cream maker). I can make more excuses, but let’s just have it out: Before I participated in this tournament, I did not own a mortar and pestle.

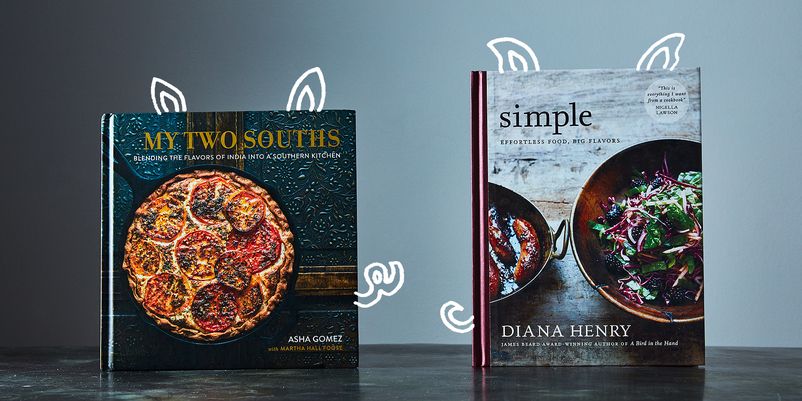

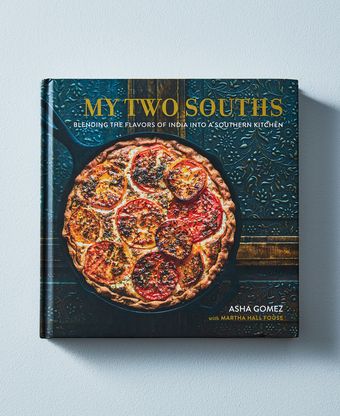

It’s not that I deny the distinction between fresh and dried spices, it’s just that most of the things I cook and bake call for powder, and bodegas everywhere sell salt and pepper dispensers with built-in grinders. As for anything that ever needed a good crack or a mashing, I never saw the need for an ancient stone tool taking up space in my cupboard, particularly when the aforementioned wine bottle would do in a pinch. I knew right away by looking at the covers of Diana Henry’s Simple and Asha Gomez’s My Two Souths that this would no longer fly—the former has that rustic, just-so vibe that just screams “farmhouse with no electricity,” and the latter says it quite literally in its subtitle: Blending the flavors of India into a southern kitchen. The inside cover page is a mortar and pestle next to some artfully arranged whole spices.

I dove into My Two Souths first, wary of complicated spice blends, and learned that Gomez found an unusual path to food-world renown. She is a fifth-generation Roman Catholic from the southern Indian state of Kerala, and grew up eating true port-city cooking from a kitchen where “kodampuli, asafoetida, and cambogia arose from cast-iron griddles and clay cooking pots.” She later moved to New York, attended Queens College, became a licensed aesthetician, and settled in the American South, Atlanta, where she opened an Ayurvedic spa. (Stay with me here.) While running the spa, Gomez began sharing her home-cooked meals with her clients. A resulting supper club of Indian-American fusion turned into a short-lived but widely acclaimed Atlanta restaurant, Cardamom Hill, which gave way to a “culinary event venue” and patisserie called Spice to Table.

My Two Souths asks for an investment upfront, in both ingredients and attention (and for me: a mortar and pestle). After the biographical introduction, there is a section covering the basics involved in creating the “sour, pungent, and camphoraceous” flavors of Keralan cuisine. Asafoetida and curry leaves sounded intimidating, but were not terribly difficult to track down, especially in New York. Ghee and coconut milk have entered the mainstream and can be found at most grocery stores. You can see why I thought Asha Gomez would be the complicated one—Indian food is famously alchemical, involving many dozens of spices in a single dish, but her recipes are surprisingly simple (with the obvious exception of curry and gumbo).

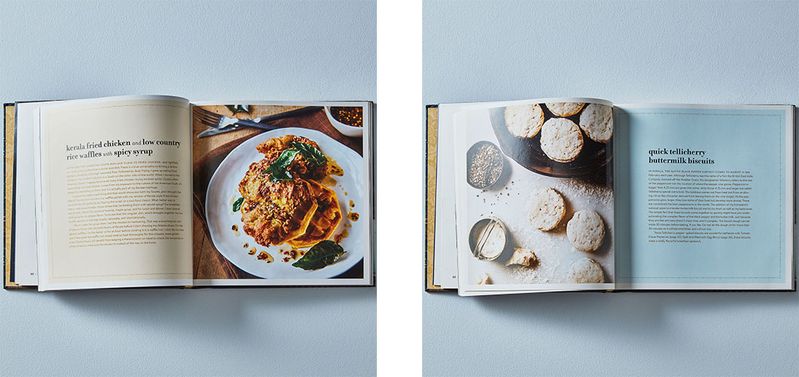

The book is organized like a chronological menu, from day starters to desserts and including “tea time,” though many of the plate lunches (pork vindaloo with cardamom cornbread, Kerala fried chicken and Low Country rice waffles) could work just as well for hearty dinners. Egg bhurji could easily be written off as “just scrambled eggs,” but it had three more ingredients than you’d ever get around to including, because when you’re scrambling eggs you’re probably not in the mood to chop shallots, jalapeño, and cilantro. Sometimes you just need that extra push to make your sad weekend breakfast into a confidence-building exercise.

I don’t tend to think of baked goods as breakfast items so much as breakfast desserts, but I had a go at some blueberry-lime muffins to give away to friends. The muffin batter turned out sticky and slow to cook, an issue that was easy to ignore because of the divine crumb topping—flour, sugar, butter, salt, cinnamon, and mace. I have never before had occasion to make that magical crumbly substance that tops coffee cakes, but now that I know its secret (butter), I am conflicted as to whether or not it should be legal as an ice cream topping (early research points to yes).

But the greatest coup of this entire exercise was Gomez’s Tellicherry buttermilk biscuits, which should frankly be The Standard Biscuit Anywhere That Biscuits Are Served. They’d go perfectly with and enhance any dish where plain biscuits are called for, from fried chicken to gravy to Thanksgiving dinner. Gomez advises doubling the recipe and freezing half; I heartily suggest tripling it. Pastry flour is absolutely required, but you will use it up in no time making many dozens of these biscuits. The combination of a fresh, fluffy baking-powder puff with the sharp heat of a cracked peppercorn is unbeatable—even the steam smells peppered.

For the most part, Gomez’s recipes are just simple enough: Her weeknight fancy chicken and rice is a true miracle of a one-pot dish, a descendant of arroz con pollo, with the rice restored to its signature Iberian yellow with turmeric rather than saffron. Cardamom pods and star anise give flavorful depth, and dried apricots, sliced almonds, and that worthy cilantro make for the most un-boring staple of a weeknight dinner. (It is crucial never to skip the cilantro, even when re-heating leftovers; a bright-green garnish will always give you hope.)

Sometimes, Gomez’s recipes seemed too simple, as though she might be leaving something out for ease of communication, or so as not to overcrowd the page. I would make her fresh thyme fish cakes again tomorrow if I knew how big to make them (the recipe said to “Form 8 cakes,” but they struck me as too large and I spread them into nine), and how much to brown them in the fryer versus in the oven. Still, any hot fish cake straight from the oven is delightful, though my own executions needed salt and pepper to taste. They also left me wishing for a creamy tartar sauce, perhaps shot through with more Keralan flavor.

Diana Henry’s Simple, on the other hand, has thought of everything—almost to a fault. Indeed, she has an entire offset section titled, “a bit on the side,” dedicated to sauces and relishes, which Gomez could have used more of. Nearly every dish has a cream sauce, like roast potatoes with watercress and garlic cream, or roasted eggplants with tomatoes and saffron cream. Henry has been in the business of “simple” cooking for over a decade—this book is a follow-up to what was published in the UK as Cook Simple and in the US as Pure Simple Cooking. (I would read an entire book on the subtle differences in US versus UK book marketing, from titles to cover art—Simple is rendered lowercase here, and uppercase there. The cover of the former has a vibrantly colorful photo of honeyed sausages with blackberry and caraway slaw, whereas the latter has has more muted pork chops with mustard and capers in a, you guessed it, cream sauce.)

I loved that Henry had an entire section dedicated to eggs, complete with a ballpoint pen doodle on a picture of a pale blue ovoid. But here is also where she lost me: The very first recipe in the book is for egg and salmon donburi, essentially a deconstructed salmon-avocado sushi roll with some scrambled eggs, down to the toasted nori garnish. This manages to be simultaneously simple and fussy, which is the general vibe of the whole book. Henry’s food is also unapologetically English. She writes that a salad of cucumber, radishes, and cherries with rose petals is “like eating a garden,” and compares the size of fregola to hailstones. She’s also funny, writing of creamy flageolets, “they’re not Michelin star but they’re satisfying, the kind of thing a chic-but-harassed French woman would make.”

And by the way, that blue egg was a Cotswold Legbar, one of her staples along with Buford Browns. Knowing your hens’ species is nice work if you can afford it, and Henry’s is the kind of simplicity that only money can buy. To be fair, she does acknowledge this in an aside:

"I care about the quality of the food I eat, and about its provenance, but I also try to be realistic about what people can afford. When it comes to flavor, though, there are some foods about which I cannot compromise: pork, butter, and eggs are the three I would prefer not to eat at all if I couldn’t get the best, as I know I will be disappointed with them."

I am all for spending a few extra bucks on very good staples, but where her recipes aren’t expensive, they can be complicated. The main investment that Diana Henry asks for besides a well-stocked larder is fuss. Her recipes on average have twice as many ingredients than Gomez’s. She’ll have you cut radishes into matchsticks; a subsection about “no-hassle appetizers” within the Salads chapter indicates that most of the salads are in fact a bit of a hassle. Her introduction also includes a subsection on “unusual ingredients,” like miso and pomegranate molasses. This is not home cooking as I’ve ever experienced it, but a certain kind of show-off home cooking—everyone has that one friend who actually uses kohlrabi and tamarind paste at home, but I am not that friend.

I have always subscribed to the theory that you order at a restaurant something you would not otherwise make for yourself, whether because of the unusual ingredients or complicated execution. Many of Henry’s recipes reminded me of ABC Kitchen dishes, especially the cumin-coriander roast carrots. (Don’t get me wrong; I love ABC Kitchen, but I’ll almost always pay a premium for someone else to do the fussing.) The carrots were actually riffed from an April Bloomfield recipe; in fact, a good number of Henry’s recipes are adaptations—she is a known and relentless tinkerer, testing hundreds of recipes per year. Melissa Clark wrote in The New York Times, “To say Ms. Henry is highly prolific is to understate the case.” Henry even adapted her New York takeout noodles from The Times and a salad from Food52 (hello). The connective tissue of this book is not so much an obvious theme, as with Gomez’s, but Henry’s ingenuity. After testing several recipes, I realized I’d rather invite myself over for lunch at Henry’s than make her food at home.

In her introduction, Henry writes that she thinks and shops for food in terms of building blocks, often with proteins at the center, though today, in the Age of Ottolenghi, we now lean more toward whole grains and vegetables. I had a difficult time finding a vegetable or salad recipe I wanted to make, because her dressings are almost always sweet, and include honey or superfine sugar, which is not to my taste. I settled on broccoli with harissa and cilantro gremolata. Her recipe calls for purple sprouting broccoli, with optional substitution or broccolini or cauliflower. I went rogue and used a big old head of plain green broccoli. A gremolata of lime, harissa, and garlic made for a beautifully well-rounded zest that also packed some heat. And I am grateful for the addition of harissa to my criminally understocked armory.

Overall, Henry’s flavors were big, as the subtitle promised, but her food was not effortless. The best stuff I made from Simple was more straightforward, with fewer ingredients and more focus—one twist rather than three. My favorites included orzo with lemon and parsley and a goat cheese and roast grape tartine. And so the winner here is Gomez, who showed me from first principles the origins of heat and spice on the most basic level: The sheer genius of coarsely pestled pepper folded into a basic buttermilk biscuit. What could be simpler than that?

138 Comments

I own so, so many cookbooks, and I cook from one nearly every day. This one is exceptional. I marked nearly half the recipes in the book, and am so excited to have new, beautiful, truly simple ways (at least, simple assuming you know how to cook and enjoy it) to use our gorgeous local produce and foraged things here in Vermont.

I read the book this afternoon over coffee, and couldn't wait to get started, so I made the linguine all'amalfitana--bucatini, walnuts, Aleppo pepper (my adjustment--all the pepper flavor, none of the heat the kids dislike), anchovy, olive oil, parsley, and pecorino.a pantry meal, so I didn't even have to run to the store to try out the book.

The recipe is similar in concept to various pastas I've made, but still notably different and unique. I did toast the walnuts first, which is my standard practice anywhere a nut is to stand alone without further toasting. Even the young kids loved it and asked for it in their lunches tomorrow.

In a few weeks when the markets have all the Spring things, I can't wait to try cucumber, radish, and cherry salad with a white wine vinaigrette that involves--heavy cream! A couscous salad with pea shoots and violets (both in my garden or yard by next week)

This book is a rare combo of pretty things that overlap in the ven diagram of cooking with things you can actually get/already have and things you really want to eat.

Reviews were enthusiastic, but somehow didn't mention all the things that really excite me about the book. Recipes are well-designed to use produce that will all appear at the same time at my local market, meaning there is a season for most of the recipes.

When was the last time you read a cookbook with a pasta section where you wanted to make every single thing--and none of them were just a bunch of crap over pasta because the author thought "I need a pasta section!"? So many cookbooks are just reheating other people's recipes, and by now I feel jaded and annoyed at reading the same thing over and over again. This feels fresh. I've made things a little like this, but never This, and for that I am grateful.

I am really sorry to hear this, though I have also had two messages to my website today - about this very recipe - saying that it had been very successful.. Are you sure your oven is getting to the temperature it says it does? I now have a thermometer to make sure the temperature on mine is correct as most domestic ovens aren't terribly reliable (they can also change temperature during the cooking period). This recipe has been cooked often by me, was further cooked by the tester and then also tested by the book's editor, so it has gone through several pairs of hands. I don't know what could have happened as I was particularly concerned that this recipe worked precisely because it is so simple. Your potatoes need to be very finely sliced and the stock needs to reach the boil before you transfer the dish to the hot oven. I am mystified why - if it was at the right temperature - this dish didn't cook in 45 minutes. Could anything else have been the problem?

Best wishes,

Diana

There is not one New Yorker with a kitchen the size of a postage stamp who owns a mortar and pestle? Or a stand mixer, which she relegates to suburbia (where I now live; I used to live in Manhattan and owned several mortar and pestles of varying sizes, along with an electric coffee grinder for when I didn't feel like pounding using my stone-age tools; the former didn’t grind them but instead pulverized them to a powder much like what the judge says she finds in her local bodegas)? From the outset, the judge makes it very clear where her allegiances sit: no stone-age tools for her. Instead, an expensive Italian coffee grinder ($229 on Amazon?), a Vitamix (mine cost almost $600), an ice cream maker (I'm guessing not the hand-crank, faux wood-barrel variety of my childhood). None of which one would find in a “farmhouse with no electricity.” Anything that calls itself overtly simple --- the very title of Henry’s book --- seems to put a bee in this judge’s bonnet. Except when she called some of Gomez's recipes too simple, which she found suspicious.

But to the books: Why wouldn’t a reader be in a mood to chop shallots, jalapeno, and cilantro if one is making scrambled eggs? Otherwise, they’re just scrambled eggs, which can be delicious (especially when slow-cooked in another stone-age tool: a double boiler), and if I, as a cook, neophyte or not, can infuse simple scrambled eggs with these flavors and elevate the hum-drum, why wouldn’t I? Why would the first recipe in Henry’s book “throw” the judge? Because it was Asian in style when the author is largely known for the use of Levantine ingredients? Why would Henry’s description of fregola, comparing them to the size of hailstones, seem to so irritate the judge that she would call it out? Henry, historically, is known not only as the creator of stellar, interesting, and multi-layered dishes that reflect the culinary fabric of the international communities in which most of us now, thankfully live; she is also a spectacular writer, and arguably the heir apparent to (the very British) Jane Grigson and Elizabeth David.

As to the issue of riffing: cookbook writers do not live and work in a vacuum. None of us do: we are all influenced by the worlds in which we live and work. If a cookbook writer decides to include a recipe for steamed basmati rice, are they then riffing on Madhur Jaffrey? When I make aioli in my mortar and pestle, am I riffing on Richard Olney? Riffing only gets dicey when the author doesn’t point to its originator with an attribution: I applaud Diana Henry for including in her headnote that she "fiddled around with a recipe shamelessly stolen from April Bloomfield"; many cookbook authors do not attribute to such a clear degree. I do not yet own Gomez’s book --- I look forward to buying it and cooking from it; it sounds terrific --- but if the judge made it a point to mention riffing, how could the judge not also point to Ottolenghi’s famous, cardamom-laden, one-pot chicken and rice dish, probably the most widely cooked from Jerusalem, that made it to the front page of the NY Times food pages (also the subject of a NYT video by Julia Moskin)? The two are very similar in vibe, although Ottolenghi’s did not include fruit or turmeric. My Two Souths also reminds me of one of my favorite books of a few years back, Suvir Saran’s American Masala, in which the New Delhi-born author includes recipes that largely had their roots in the American South (where his partner is from), then tweaked some of them with the addition of Indian flavors, thus reflecting the couple’s home kitchen where their two cultures are blended. (There is also a wonderful egg recipe in American Masala that calls for jalapeno, curry, and chiles, much like Gomez's scrambled egg recipe, the combination being an Indian culinary trinity.) Again: two different books by two different people writing on the same subject. There will always be crossover, certainly. But for the judge to mention the act of “riffing” with such an accusatory lilt and without context left, as Ian Rose said below, a bad taste in my mouth. I would have hoped for a more even-handed, balanced, fair approach to the judging in this regard.

I have already cooked from Diana Henry's book; I look forward to cooking from Asha Gomez's as well.

I'm not sure why a type of British egg is less a reason to dislike a book than "My Two Souths" basing a recipe on Carolina Gold Rice, in fact of the two "My Two Souths" is far more dependant on geography to sell its concept.

Perhaps despite her New Yorker credentials the reviewer is a bit more Trumpian than she would like to admit.

I don't disagree with the outcome of this piglet, "My Two Souths" is a very good book as is "Simple", it's not Diana Henry's very best book but any DH book is sublime.

I'm not sure why a type of British egg is less a reason to dislike a book than "My Two Souths" basing a recipe on Carolina Gold Rice, in fact of the two "My Two Souths" is far more dependant on geography to sell its concept.

Perhaps despite her New Yorker credentials the reviewer is a bit more Trumpian than she would like to admit.

I don't disagree with the outcome of this piglet, "My Two Souths" is a very good book as is "Simple", it's not Diana Henry's very best book but any DH book is sublime.

Burford Browns and Cotswold Legbar eggs are widely thought to have a great flavour - that's why people buy them. They are more expensive but I wouldn't call them 'fancy packaged' eggs, and eggs are a cheap form of protein so I don't mind spending more on them. They comes in boxes, like all eggs, they just happen to brown or blue boxes. I'm not the only person who buys them for flavour. They also come from a good company, who practice good animal welfare. There's nothing wrong with buying eggs from farmer's markets (and there are plenty of 'fancy' overpriced farmer's markets around) but I've just found Clarence Court eggs to be - consistently - the best. I also go through a lot of eggs so usually buy them a couple of times a week, and the markets are only on at the weekend. I promise you I don't buy anything just because they're 'fancy'. I honestly buy ingredients because they taste good.

And for the skill necesarry for Ms Henrys cookbooks I would say, as long as you are able to read, all the recipes are easily achieveable for everyone.

A minor, yet ilustrative example: A commenter below relayed the fact that "Every British supermarket tells you the breed of chicken right on the carton, and they are many and varied." Which perhaps shows that the reviewer's snarky comment about "knowing your hens’ species is nice work if you can afford it" says more about her own lack of cultural awareness than it does about the cost of factual information. Too bad she evidently wasn't able to afford a little more of the latter herself.

In the beginning of her often supercilious review, Killingsworth says that Simple has a “just-so vibe that just screams “farmhouse with no electricity,” and the latter [My Two Souths] says it quite literally in its subtitle: Blending the flavors of India into a southern kitchen.” What is “quite literally” supposed to mean? That all kitchens in the South are rural and rustic? Gomez lives in Atlanta, which is in the top 10 metro population areas in the US! It appears that Killingsworth holds an ill-formed view about both the South and suburban areas. This conceit is sprinkled throughout the review with comments like stand mixers being “a suburban indulgence”.

This apparent belief that anyone living outside the city is beating rocks together in a candlelit cabin is absurdly juxtaposed with a populist attitude. Killingsworth knocks Henry by chastising her for knowing the breed of her chickens, by saying the recipes are “show-off” home cooking, and by taking a subtle dig with the substitution of “plain old green broccoli” for sprouting broccoli. She thinks sprouting broccoli is a bridge too far yet she believes curry leaves are accessible, a baffling contradiction. She also falsely asserts that Henry’s recipes have “on average have twice as many ingredients than Gomez’s.” I looked through the ingredient lists for 10 random recipes from each book (using Eat Your Books, which excludes common pantry ingredients like salt), and Henry’s recipes averaged 7.18 ingredients to Gomez’s 7.36. It feels like Killingsworth just didn’t like the title of Henry’s book and therefore strained to portray Henry as effete and pretentious. The alternate theory is that Killingsworth suffers from guilt about her own urban, apparently upper-middle-class position. Either way, the review is callous and condescending.

I haven’t cooked recipes by either author so I came to this review without any preconceived notions, but the review directly contradicted what little I know about Henry through articles I’ve read. If I based my opinion of her from this review, I do not think it would be accurate. The review did, however, make me happy that I recently purchased of four of Henry’s books at a secondhand shop. I look forward to making unapologetically English food with my comically tiny version of an industrial-size dough mixer.

I've been an admirer of Ms. Henry and an avid user of her recipes for years. "Crazy Water, Pickled Lemons" is one of my favorite cookbooks -- though it's so much more than a cookbook -- ever. Read it and see for yourself. I bought "A Bird in the Hand" when it was a Piglet contender; I recommend it not just for the recipes, but for the possibilities it offers. Nearly all of the (generally easy) components in Ms. Henry's recipes work brilliantly when adapted for other dishes. In her writing and her cooking, I feel like I've found a kindred spirit.

And Darcie B, I like the cut of your jib!

Cheers, and Happy Friday, everyone. ;o)

The tone got snarky. I felt like she really took a turn into the nasty when she hammered Henry for knowing the breeds of chickens her eggs come from but what really sent me over the edge was the "show-off home cooking". Talking about that friend how actually uses kohlrabi and tamarind paste.

I love to cook. I have cooked and baked for decades. I have lived in apartments and I know live in a spacious farmhouse (it has electricity, btw) and no matter where I was I had a well stocked kitchen. Now in my farm house I have a large walk in pantry and yes, I have pickled my kohlrabi from my garden and there is tamarind paste in my pantry. I blog about my cooking adventures and have suffered a lot of ridicule for "showing off". I can say first hand that it has nothing to do with showing off. It has EVERYTHING to do with enjoying to share my passion and discovery. Heck if I can encourage someone to try something new great!

Was so offended by the second half of this review I had to skim read the rest of it. I wasn't going to comment because I knew I would rant. Then I got to the comments and saw the greater majority share many of my thoughts.

It's one thing to not be a accomplished cook and be asked to review cookbooks for Piglet. It's another thing entirely to obviously dis on those who love to cook and seek out great ingredients. I sincerely hope this reviewer is not asked back for future Piglet contests.

You have all been very kind to write (and very empathetic too). I am - honestly - very happy for My Two Souths to go through. It is a great book - I was given it as a gift the last time I was in New York - and it has more of a story than Simple does. It is unusual and original. I do, however, think the review is mean-spirited in the extreme and, as has been pointed out, just plain inaccurate. But that generally says more about a reviewer than it does about the subject under review. Congrats to Asha. And a cheer for decency, in whatever we write and whatever we do.

Oh, and a few more things... Since when is "It tastes like a garden." a BAD thing? And why knock someone from the UK for sounding like they're, you know, from the UK? And what's with saying that a recipe from one book needed a creamy sauce but complaining about the other book's creamy sauces... Blergh. This review bugs me.