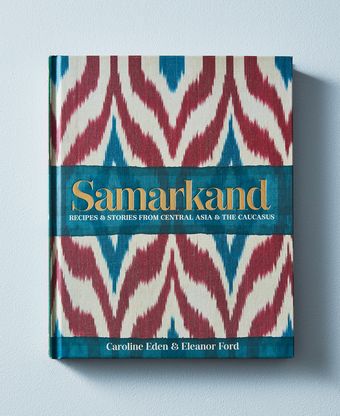

These two cookbooks—Samarkand and Taste of Persia—are twins, separated by a mountain range or two. In each book, an outsider ventures to Central Asia and attempts to describe the food traditions of a geographically disparate civilization. There are plenty of recipes, but also stories of human encounters—a bazaar here, a village there, and my favorite, a visit with the “Mountain Jews of Azerbaijan.” (I like to think of myself as a Mountain Jew of Vermont.) Both books have glorious photographs and cutesy regional maps.

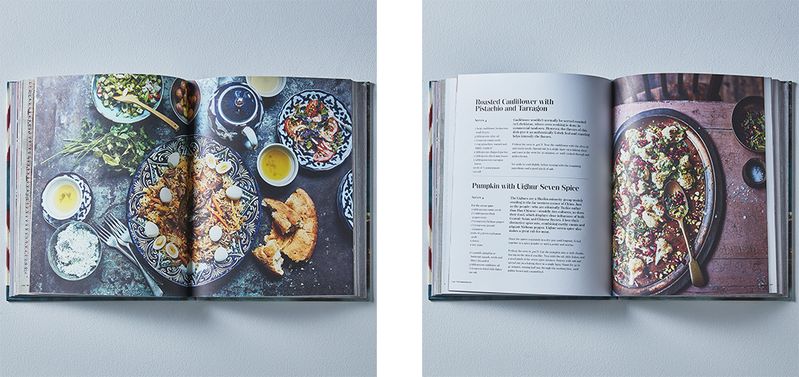

For Taste of Persia, author Naomi Duguid assigns herself the region influenced by Persian civilization: centrally Iran, but also parts of Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kurdistan. Caroline Eden and Eleanor Ford take the trading city of Samarkand as their capital, then caravan along the Silk Road to Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and other Stans, as well as the Caucasus region, going as far east as Uighur China and as far west as Turkey. There’s little to separate the two books in style and approach. The travel narrative in Taste of Persia is more personal and emotional; Samarkand leans anthropological.

So let’s head to the kitchen! Unsurprisingly, Samarkand and Taste of Persia overlap heavily in recipes and staples. Both have big sections on rice dishes and breads. Both make abundant use of dill, parsley, and cilantro. Pomegranate molasses, dried apricots and barberries, saffron, and nuts are everywhere. I’m an ignoramus about these two food cultures, but Duguid’s Taste of Persia feels more authentic to me: She’s a little less compromising about ingredients, describes techniques at length, and includes a rich glossary.

I ended up cooking a full meal from each book: A soup, a vegetable, a starch, and a meat. Taste of Persia won the coin toss and went first. I adore dried apricots, so I debuted with a dried apricot and wheat berry soup, its murky orange jollied up with a ton of chopped fresh herbs sprinkled on top. Not a triumph: It was sour, sweet, and heavy—neither refreshing nor hearty.

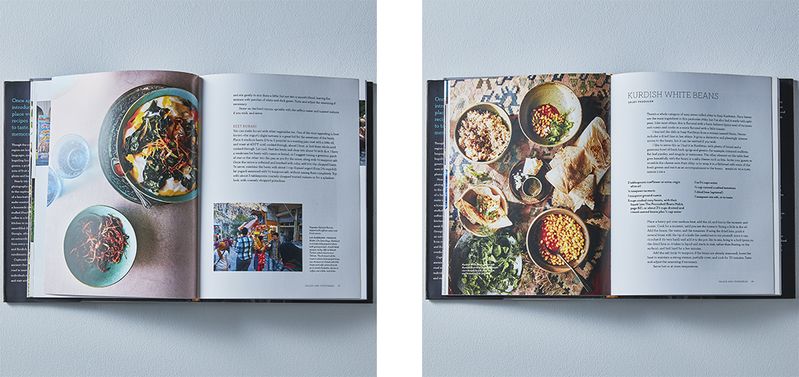

On to the main dinner: a koobideh kabob of grilled ground lamb and onion, a spinach borani with yogurt and onions, and a Kurdish black rice consisting of Arborio rice and walnuts cooked in pomegranate molasses. It was, my friends, a bummer. The koobideh was dry and sadly flavorless. The black rice, though it gets an A-plus for weirdness, shared the sour, heavy sweetness of the apricot soup. Most disappointing was the spinach, largely because there’s a misstep in the recipe: The dish is supposed to be a mixture of cooked spinach and yogurt, topped with fried onions. So says the introduction to the recipe! The photo shows wonderfully dark brown, obviously crunchy, onion strips! But ack, the recipe instructs, “fry the onion till translucent and touched with color, about five minutes.” I followed the recipe rather than the photo, and regretted it, creating a slimy mush.

We reconvened one Sunday later for a meal from Samarkand. My kids were cynical and put-upon, burned by Persia. The Samarkand menu looked very similar on paper: Tajik Green Lentil and Rice Soup, Spicy Meatballs with Adjika (from Georgia), Melting Potatoes with Dill, and Radish, Cucumber and Herb Salad.

Our faith was restored by the first spoonful. We demolished the lentil soup, which was topped with a delicious oily-herbed slurry. It was easy-peasy to make, and I am going to incorporate its rice-in-soup technique for other soups. Samarkand then ran up the score: The Georgian meatballs stayed moist thanks to milk and fatty ground pork cutting the ground beef. Most of us also liked their tomatoey, herby adjika sauce. The melting potatoes, mostly butter and dill, didn’t feel particularly Central or Asian to me, but the kid gobbled them up. And the radish salad’s crunch and bitterness swept away the lingering fat from the meatballs and potatoes.

In 1383, Tamerlane left his capital Samarkand, marshalled his army, and set forth to conquer Persia. Over the next five years, his horde laid waste to the remains of the Persian empire. In Isfizar, Tamerlane cemented his enemies—alive—into the walls of the city. In Isfahan, he crushed a revolt by killing everyone, and built 28 towers out of the skulls of 100,000 victims. He reduced Herat to rubble, and sacked Zaranj. Tehran surrendered, and was spared death, but not heavy taxation. Then, triumphant, Tamerlane marched home to Samarkand.

And so it is again. In the competition between two mighty cookbooks, Samarkand is a colossus, victorious. In the end, the proof in the pudding was the actual cooking. We open our family gates to Samarkand.

31 Comments

http://www.tipsybaker.com/2017/03/ruining-russian-counts-castle.html

However I have already cooked an entire meal from Samarkand - it was delicious. Somehow the recipes just seemed more approachable.

I would have been happy to see either book win, but suspected Samarkand might.

Great review!

I'd leafed through Samarkand, but put it back. I was intrigued by the round one review though, and now round two has convinced me. If I love Persia (and I do recommend it), I guess I'll really like its banisher.

Who knew?

These are all things that real people actually cook. They are perfectly appropriate for a historical or anthropological look at local food ways.

But in a bit piglet cookbook, I don't expect to see the Persian equivalent of beans on toast, or that weird Midwestern US beast, the Chinese chicken salad with crushed ramen noodles.