The high priestesses of the Piglet set me up with cookbooks from two serious hitters in the restaurant world: Suzanne Goin of Lucques, A.O.C., Tavern, and the Hungry Cat in Los Angeles; and Einat Admony of Balaboosta and Taïm in New York. They arrived in my kitchen at roughly the same time that Time story about the so-called “Gods of Food” set off a brushfire of controversy about whether the magazine had done enough to locate -- much less recognize -- women in the pantheon of professional food.

This was a funny coincidence. Because, of course, here were two who walk near those heights: Goin, with four restaurants to her name and a direct line back to Alice Waters, for whom she worked at Chez Panisse; and Admony, a falafel maven in New York who transformed street food into a kind of sacrament at Taïm, and home cooking into practically a religion at Balaboosta.

To their tracts I would turn!

But of course religion is a terrible lens through which to examine cookbooks. (Maybe the food world too?) It leads to the worship of false idols. Cookbooks are not sacred, anyway. Their purpose is not devotion but use.

The better analogy is pornography. Cookbooks are designed specifically to arouse. They excite in us the passion to cook or at any rate to consume. The best ones make us want to do that right now.

Or they don’t. And those are cookbooks we do not use.

Does the cookbook make you want to cook? Does it do so again and again? For a cookbook to win the Piglet, these questions must be answered affirmatively.

I have cooked extensively from Goin’s first book, Sunday Suppers at Lucques, to unbelievable effect at dinner parties and family suppers alike. It stands butter-stained and thyme-fragrant on my kitchen bookshelf, its binding cracking from use. Goin’s marriage of Californian values and flavors to the cooking of Europe and the Mediterranean rim is just, like, crazy-making in its deliciousness, even if it requires hard and considered work in the kitchen beforehand. Goin is a project cook, even when the cooking is putatively simple. There is always another step to take to make her dishes, a subsequent recipe to cook, a need for an ingredient that there is no way you’re going to find on a weekend in Brooklyn even if you have a professional’s knowledge of places to buy specialty items and, should this fail, Florence Fabricant’s mobile number on speed dial (and I have both).

Pork confit? You need three quarts of duck or pork fat to make it. The ingredient -- pork confit is not a dish for Goin, but simply an element of a larger one -- appears in Sunday Suppers and shows up again in The A.O.C Cookbook. Come on, lady. I braised a pork shoulder in dark beer with a lot of aromatics instead and then followed the recipe from there and it was about the greatest thing I had eaten in half a year. I’m sure I would say a full year if I had made the actual recipe. But I am not tracking down all that fat for anyone.

Cooking Goin is complicated. Her recipes -- written with exacting detail and endless instruction -- reward those who follow them closely. Put another way, you can cheat as I did with the pork, but not always. To cite an example from Sunday Suppers, I have made Goin’s Devil's Chicken Thighs with Braised Leeks (based on a Julia Child recipe) approximately one million times since the book came out in 2005. About three years in I started to take shortcuts, not braising the leeks ahead of time, trying to make the dish more of a one-pan meal. This diminished the quality of the end result greatly. I am back to following the instructions as closely as if I were rehearsing to work in her kitchen and not get fired. The dish takes all day to make. It is back to being fantastic.

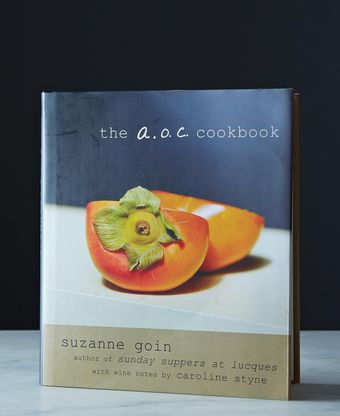

The A.O.C. Cookbook owes a great stylistic debt to its older sister. It looks and feels and reads similarly, and cooks just as well, with beautiful photography from Shimon and Tammar Rothstein. The books are a hell of a pair.

For this exercise, I noodled around A.O.C. for weeks. Here were recipes to entrance the imagination, to imagine serving to applause in apartments with more than one floor, with separate entrances, with gleaming kitchens and the luxury of time to cook in them. (Also a wine cellar. Caroline Styne, Goin’s business partner, provides excellent notes on pairings throughout the book.) The delights piled high in the brain. Braised Duck with Madeira, Kale Stuffing, and Dates. Striped bass with roasted beets and blood-orange butter. Pork Confit (my attractive nemesis!) with Caramelized Apples and Cabbage in Red Wine. Parsnips and Turnips with Sage and Prunes. Goin writes about these things as if you could knock them off in an hour, which perhaps you could if there was a team of underlings working for you who could do the shopping and the prep work. But for the home cook caught in the time famine of life in New York, please understand: There is not much here for the kids on a weeknight.

Except, there is. Those root vegetables, for instance, pair beautifully with a simple roast chicken. And I managed to pull off a dish of cinnamon- and cumin-scented lamb meatballs in spiced tomato sauce, with feta and mint, in just over an hour. It made for an insanely good meal with warm pita on the side, less a project than a considered block of time in the kitchen working with children, and it punched well above its weight in matters of flavor, thanks to the interaction of the lamb fat with the fresh breadcrumbs and spices in the meatballs, and the thick tomato sauce, fiery and almost sweet, that surrounded them.

The verdict of our family’s most fearsome recipe critic, age 10: “I would eat this every week.” Me, too.

Balaboosta fares less well on this scale -- and I write this as a major fan of the restaurant from which the book takes its name. Our best run at excellence was with a platter of Admony’s mother’s chicken with pomegranate and walnuts. Cooked directly from the recipe, with no changes, it was slightly muddy in aspect and flavor, but pretty good for that: Israeli home cooking, I suppose, untrammeled by restaurant fanciness. “It was okay,” said our Antoinette Ego, to nods from the rest of the clan.

The recipes in Balaboosta are grouped interestingly: dinner-party dishes; kid food; quick-and-easy dinners; comfort food; barbecue options; healthy meals; slow-cooked ones; Israeli ones; fancy ones; romantic ones. The trouble is, very few of them appeal -- or at any rate appeal to me. With the exception of Mama Admony’s chicken and a marvelous roasted eggplant slathered with tahini and lemon juice, then covered in an herb salad, I found it actually difficult to find food in the book I wanted to cook.

Sometimes this was because of the simplicity of the dishes described. I don’t need a recipe for chicken fingers, for instance, or roasted Brussels sprouts (though I did like the addition of a grated Anjou pear to the roasting mixture). Other times it’s because, well, I don’t want a recipe for popcorn with chocolate, nor one for chicken baked with ketchup, apple juice, paprika, onions, and a little cumin. (I can pick that up at the airport.)

And I simply don’t buy a recipe for chili that name-checks the Wendy’s version in the headnote that accompanies the instructions. Nor one for a “Morning Orgasm Cocktail” that declares, “With two kids who still like to finish the night in our bed, special morning time doesn’t happen as often as I’d wish, so this drink has become a bit of a replacement.”

I won’t list the ingredients.

The A.O.C. Cookbook advances.

85 Comments

This review, although of an entirely different cookbook, has both reassured me and inspired me to go back to the one I already own. What a nice surprise.