I have to admit to being a bit nervous about this whole Piglet business; I had to go out and get a new pair of reading glasses just to begin. (The sad truth about turning forty-something is that one day you wake up half blind.) I took this task very seriously, and it had to start with new glasses.

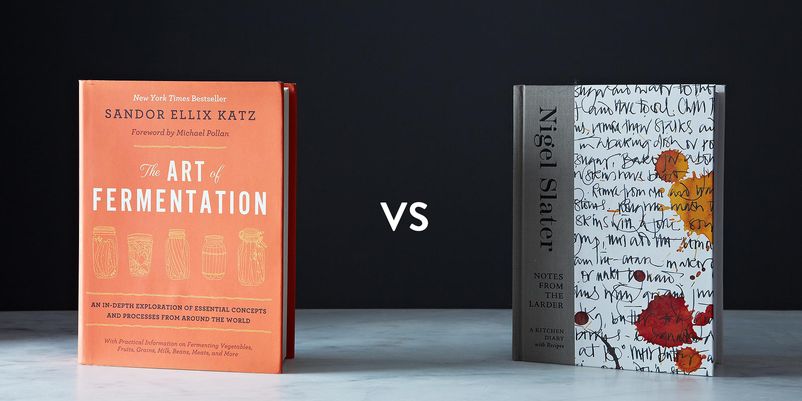

Shortly after agreeing to judge, two books arrived in the mail. There were two packages, much tape, and sturdy cardboard. I ripped furiously into them. First up was Nigel Slater's Notes from the Larder. It's a weighty book exactly the same size as his previous books; Tender Volume One and Two. I love the size of his books -- they just feel right in my hands, neither too big nor too small.

Right away, I was drawn into Nigel's book. I opened it to find marbled end pages that look like a swirling chocolate pavé, and on the next page, a photograph of a dusty blue Chinese notebook and a hand-torn fig. I am partial to ripped fruit; who needs a knife? I was hooked. The design and photography of Slater’s book is so beautiful and consistent that I'm immediately putting on a pot of tea so I can curl up and dream about the likes of Winter Leaves with Gherkins and Mustard or A Plum Water Ice for a summer’s day. I start to plan dinner parties in my head.

As I ripped open the second package, the tiniest bit of neon orange peeked back at me. Book two: The Art of Fermentation by Sandor Ellix Katz. This was going to be tougher than I thought: It’s a much bigger book than the other, and it immediately seemed a bit daunting. Even still, I begin to feel a bit excited about fermenting anything and everything, about lining my pantry with jars of fermented foods, sharing them with friends, and maybe starting a fermentation swap. The Art of Fermentation inspires such things. My mind was swirling with one look at the table of contents: Fermenting Sour Tonic Beverages, Growing Mold Cultures, Fermenting Beans, Seeds and Nuts. This book was definitely going on my list to give to friends.

I sat down with both books and gave them a once-over. My first reaction, once past the beauty of Nigel’s book, was “Will I learn anything new?” After my initial look at both books I was torn; while I was initially visually hooked on Nigel’s book, I couldn’t help wondering how these recipes differed from his other books. His previous publications have made me realize I can use his recipes more as inspiration for my cooking rather than a step-by-step guide. He has been such a good teacher, but I wondered if I would get anything revolutionary from this book. Or would it be just another pretty face on my shelf? I was feeling as though Katz’s book might be the clear winner here -- the obvious choice just by the nature of the fresh subject matter.

At first glance they couldn’t be more different, and I felt a little uneasy about comparing them: one is a more traditional cookbook, with a strong author narrative, the other an exploration of fermentation techniques from around the world. Still, I was excited right away by both and was eager to jump in.

I set to reading each from page one, starting with Katz’s. As a photographer, cook, and traveler, I always enjoy looking at different food cultures, so I was looking forward to mastering some new techniques and learning the history of the fermentation process. I’m also the perfect audience for Katz’s book: I own his two previous books, and over the course of the past few years, fermented foods have become a permanent part of my daily repertoire; It’s not unlikely to find me pickling green elderberries or ramp scapes, and sauerkraut has made its way into our daily diet. My refrigerator is never without fire cider or fermented garlic and cumin. I understand the immense importance of fermented foods both for the economic and health benefits that they hold. As Michael Pollan states in the foreword of Katz’s book, “The Art of Fermentation is much more than a cookbook...Sure, it tells you how to do it, but much more important, it tells you what it means and why an act as quotidian and practical as making your own sauerkraut represents nothing less than a way of engaging with the world.“

By the time I got midway through Katz’s book my eyes were bleary. It is impossibly detailed, and somehow not quite detailed enough; the very core of the book felt a little empty, while at the same time it was bleeding excessive information. I was having trouble following Katz’s train of thought, which fluttered from historic information to personal experience and back again. It’s so chock-full of anecdotes and random historical facts that it stumbles over itself. At times, it was like chewing on an incredibly tough piece of meat.

Depression and self-doubt were starting to set in. Am I really not enjoying this book? What’s wrong with me? This is a highly anticipated book from the godfather of fermentation himself! He has inspired countless people to line their counters and cellars with crocks of bubbling living liquids and vegetables and meats! I couldn’t understand how I had enjoyed his previous books so much more. I already understood the basics from Katz’s previous books -- a prerequisite, I found -- and I wasn’t really getting any further here. And tor me, the design of the text pages was part of the problem; my head hurt from just looking at them, crammed with text and no breathing room. There are anecdotes called out in pink boxes surrounded by illustrations of jumping microbes, which I struggled to find any real rhyme or reason to. There’s an aside in which a woman writes about sculpting tempeh into the form of a turkey. On another page there is a recipe for a millet polenta. Throughout the book there are seemingly decorative illustrations of various things, like a bowl of butter or an eggplant or a mason jar. I didn’t think the overall design of this book was universally user-friendly; instead, at times, it takes an elitist approach in assuming that the reader already understands the basics of fermenting.

If you decide to press on, there are a few ways you can use this book. You can either start at page one, as I did, or go right to the comprehensive table of contents and choose what it is you’re interested in. Once you find what interests you, you may or may not find an accompanying recipe. I went to Kevass. The recipe for traditional bread Kevass is buried deep in the text -- and uncovering it is a bit of a chore.

Katz states that this is less a recipe book than an exploration of concepts in fermentation, but I would have preferred what recipes were included to be more ordered and structured, and at the very least, called out. Why make us work so hard for them?

I worked anyway, and found a few things to cook. I chose his Cultured Cabbage Juice, which I’d read has amazing anti-inflammatory properties and is full of the wonder vitamin U. It is said to taste something akin to rotting compost. Was I really up for this?

I followed the instructions closely but still had questions: Should I add salt to the cabbage slurry? Should I be using filtered water? After a few days of fermenting, what should the ripe cabbage taste like? Will it be bubbly? How much will it yield after I discard the solids? If I save the solids, what can they be used for? I understand that Katz’s whole idea is for us to experiment and create our own ferments, I just wished that it were a bit clearer; a few visual clues would have been helpful as well.

I also made the Ginger Bug, which is the starter for a ginger soda. Again the recipe was vague: Grate a bit of ginger with the skin into a small jar, then add some water and sugar. Stir frequently and add a little more grated ginger and sugar each day until the mixture is vigorously bubbly. How much is a little? How much am I looking for when it is finished? I had to research elsewhere to find these answers. With a book this big and dense, I shouldn’t have to go to other sources for clarity.

Though Katz is clearly an authority on fermented foods and is passionate about what he does, I feel that this book, albeit packed with information, lacks clear direction and focus.

With this in mind I approached Notes from the Larder. Right away I felt relief with the ease at which I could understand the flow of Slater’s words. He is an incredibly visual writer with a clear, succinct style that is both personal and instructive. The book is broken down by months with recipes dated to a specific day, but as he tells us in the introduction, these are not all from a single year but collected over the years: “Between the pages of this book are those days, hours and moments spent in the kitchen that I enjoyed enough to make notes about. The dish of quinces baking in the oven on a winter’s day; a hastily assembled salad of chicken, fresh peas, and their new shoots; a bowl of sweet potato soup for a frosty evening; a steak tossed with chile sauce and Chinese greens; little cakes of crab and cilantro to eat with a friend, straight from the frying pan.”

Each section starts with two photographs of the season and no other text, save for the month, and together they lead us into each season with an emotional reaction. January is frosty and cold while April is all about bloom and new growth; September takes us to woodland berries and fading Dahlias. Each month starts with a simple story, a stream of consciousness of sorts that will lead us into the first recipe of the section. On September 6th, he writes about picking plums and eating them just as they are. On September 8th he writes a diatribe on his obsession with waxed paper and the like. This kind of treatment makes the book immediately real to me. I sense the voice and the personality behind it, and I feel as though I am speaking with a friend over a cup of tea.

I love that Nigel states in his introduction that he is not a chef but rather a home cook who writes about food. As such, his food is simple and approachable, and he cooks with an open and collaborative approach. He says he is never happier than when a reader uses his recipes for inspiration. In this respect I feel he has a lot in common with Sandor Katz; both authors inspire and encourage an open exchange of ideas rather than setting hard and fast rules that one must follow, but Nigel is just clearer from the get-go. He gives us a much more translucent jumping-off point.

Though they are broken down by month, many of the recipes in this book transcend the seasons; I find recipes I can make any time of the year. As I flip through the pages, I begin looking forward to making a Frittata of Peas and Spring Herbs, A Soft Lettuce and Hot Bacon Salad, and Elderberry and Apple Pancakes. Though his other books are full of similar recipes, I find myself wanting to make something from every season. I know I can easily substitute if there is something I don’t have and the recipe will still be as good, since they're set up for us to interpret as we may -- and we’re encouraged to make our own mark.

This book is gorgeously illustrated with Jonathan Lovekin’s stunning photographs. The light is quiet and never overshadows the food. He captures a dish in its best moment, right from the oven at times, still bubbling, dirty pan and all, as he did with the Chicken With Olives and Tomatoes. And the ripped fig on the first page is such a simple gesture, but it’s captured beautifully. This food, and these photographs, are neither forced nor stuffy nor over-styled. There is a conscientious absence of superfluous props, so the food stars in each photograph. There is no distraction.

The text pages are clear and the recipes easy to follow -- and easy to find. Nigel teaches in a simple, straightforward manner, slipping in the wisdom without my realizing it, like his gentle instruction on browning meats: “the key is not to tinker.” This is so much more than a cookbook.

I do wish the recipes were listed in the table of contents, instead of the list of the twelve months of the year that appear there in their place. I like to peruse a book starting there -- it’s my way of quickly deciding if I want to pull it off the shelf or not.

I decided to cook something warm, as the days in which I reviewed were exceedingly dark and wintry. I made A Hearty Pie Of Chicken and Leeks and the Rib Ragout with Parpardelle, both of which were amazing. I had a couple questions with the chicken and leeks, and, while it was delicious, I ended up with about a third too much filling. I thought perhaps my leeks were too large, but then it might have been better to list the weight or measurement of the chopped leeks rather than asking for two leeks, as vegetables can vary in size to such a great degree. That aside, the taste was unbelievable, and I would most definitely add the recipe to my repertoire. The second dish I cooked -- the ragout -- was a stunner, too, the recipe spot-on and easy to follow.

In the end, Nigel’s book is the clear winner to me. It shines on so many levels: from the design, to the writing, to the photography, and to the immense effort that has clearly gone into recipe testing. Though the recipes aren’t revolutionary and likely won’t have a strong social and political impact on our lives or our food system, in the end it's more inspiring to me than Katz’s behemoth of a book. I will use Notes From the Larder; it will not just gather dust on my shelf.

69 Comments