I rarely cook from cookbooks. I finger through the cool pictures and scan the ingredients, but mostly, they make my library look cool.

Dessert books are different. I actually use them, and they sit on my kitchen counter dog eared and dirty. There’s a quiet zen to measuring and scooping that makes the process of using one pleasant. A good dessert recipe is about trust; I don’t question authority, but instead allow myself to be led through a series of instructions while my brain drifts in and out of focus. So I was relieved when I got these two greatly anticipated dessert books to review. And then I realized they couldn’t be more different: Aside from the fact that both live in the dessert section of your local bookstore -- please support your local bookstore -- they have nothing else in common. Reviewing them would be difficult. Here goes:

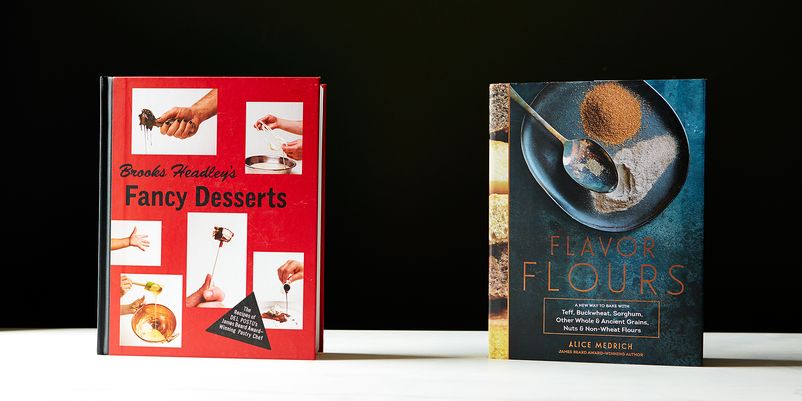

I’ll start with the more conventional book, Flavor Flours. Alice Medrich is a god among mortals; I own all of her books, and so should you. I’d be lying if I said I never pilfered one of her recipes to enhance a dessert on my menu. Her truffles are legendary, her lemon bar is the touchstone for all others, and her chocolate torte can’t be improved upon. Her body of work (this is her eleventh book!) is known for its precision, elegance, and reliability. Flavor Flours fits right in.

She tackles the world of wheat substitute flours with an approach that is both familiar and refreshingly bold. This volume gives ancient grains the lengthy conversation they deserve; it eschews the polarizing topic of gluten-free in favor of a lusty-yet-educational approach to working through our unfamiliarity with flours from corn and buckwheat to teff and sorghum. (Here’s an example of the resource page being quite helpful -- some of these flours are hard to find.) It’s filled with logical instructions, majestic photography, and plenty of helpful substitution ideas. She’ll confidently assume you have some prior baking experience, and she doesn’t cut corners for the sake of novices. (If a recipe doesn’t work, it’s your fault, not hers.)

Medrich is adept at coaxing deep flavors out of recipes as simple as her Buckwheat Sponge Cake -- which sounds and looks odd but the nutty, almost savory finish is so haunting I know I will make it again and again. Her Chestnut Jam Tart is a great example of something so familiar and recognizable and yet unlike anything you’ve ever tasted. The decadent, taut crust gives way to a chewy center that’s both impossibly soft and crunchy at the same time -- it’s easily the best dessert I’ve had in my mouth this year. And recipes like the Corn Flour Tea Cake are easy enough to instantly become a staple in your repertoire. All throughout, it’s evident how much research and testing went into this book.

As with any compendium of recipes, some ideas can seem to overreach. The rice flour beignets were tasty, but I wouldn’t put them above a traditional wheat flour and lard recipe. In her introduction, Medrich explains that she made a decision not to introduce Aboriginal recipes -- instead she chose to focus on the familiar canon of Western desserts. I wish she would have ventured more into the unknown; teff and sorghum offer a world of exotic possibilities that I would have loved to delve deeper into. And what about the dizzying variety of sweet cakes and dumplings that rice flours have contributed to Asian cultures? As I read and cooked my way through her book, I was thankful for her exhaustive treatment -- but also left feeling like I wanted more of a cultural context from whence these delicious flours came.

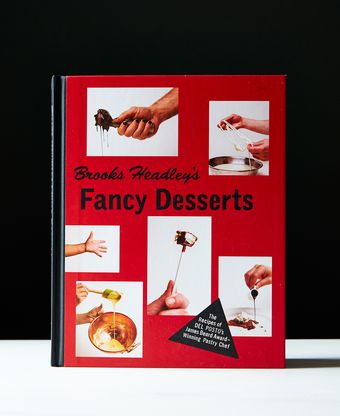

Which brings me to Brooks Headley’s Fancy Desserts. For him, everything is a cultural context. You don’t navigate through his recipes in a vacuum; you listen to them through his lens of punk rock, his sardonic New York City attitude, his Holden Caulfield-esque skepticism of anything that smells like it came from a “pastry chef” kitchen, and most importantly, his contagious passion for what he does day in day out.

Books like his are not easy to digest; they involve a level of commitment that, frankly, most home cooks aren’t willing to invest. He can be self-deprecating about this, so let me clarify something before we go any further: You will never make desserts like Mr. Headley. You may buy his book and faithfully follow his recipes, but you will not recreate his desserts on the level that he does. (If you’ve been to Del Posto, then you know what I’m talking about.)

So why should you crack open this book at all? Therein lies the beautiful contradiction: It is precisely in that failure to reach perfection that you will find your way to becoming a better cook. Headley doesn’t assume that you have prior baking experience. He doesn’t care. The recipes do not follow a logical course; they are at times mercifully short and frustratingly abridged. You’ll feel helpless because you don’t have Tristar strawberries. You’ll feel angry reading that his tangerine dessert is just a tangerine over cracked ice.

But you’d be an idiot not to make the Cucumber Creamsicle -- a dessert that so fragrant, sweet, and savory that it forces you to rethink your notions of what a “sweet” dessert is. Or the Sbrisolona, a cookie-cake hybrid so addictive that you don’t care that he doesn’t tell you what it is for or how to pronounce it only to discover later that it’s a component on a dessert in a different part of the book. He takes Brown Butter Panna Cotta, which sounds so mundane, to another stratosphere by making it a three-day process. Set in a plastic lid, it’s the thinnest panna cotta you’ve ever had -- and the book is full of little details like this that just blow your mind. All of these desserts will alter the rest of your life, if you have the patience to make them. They’re that good.

Fancy Desserts, with its recipes connected like a mystery novel, can be confusing, illogical, hilarious, disarming, vulnerable, and intimidating -- and I could not put it down. Part culinary manifesto, part punk rock tapestry, part New York City folklore, this book is not just a fascinating read, it’s a portrait of a person, of a time, and of a place so unique you feel lucky to live it through the pages of a book. I wish more chefs were this honest about themselves. Hell, I wish more people were too.

What I will say is this: Don’t attempt to make a recipe until you’ve read the whole book -- every page, cover to cover. Let it sink in. Listen. Don’t just turn to page 62 and start pulling out your measuring cups. No, you may not have Tristar strawberries, but what’s important is that you smell, touch, feel, and build up your vocabulary of ripeness, of taste memory. It’s important that you be aware. Understand that first, and then start on the recipes. If that isn’t zen, I don’t know what is.

Alice’s book is measured elegance. With her, you get to cook the perfect recipe. With Headley, you get a chance to be a better cook, and maybe, if you really listen closely, a better person.

56 Comments

" Lee attended college at NYU graduating Magna cum Laude with a degree in English Literature. At 22, he chose to pursue a culinary career instead of a literary one."

Yay, edward!

Edward Lee is a marvelous writer. Reading his stories makes me wish he lived next door.

The elegance of the review itself is a joy to read. Thank you.

"All of these desserts will alter the rest of your life, if you have the patience to make them." I celebrate the fact that such cookbooks exist (and work!), but isn't that what restaurants are for?