When ranch-dressing lovers grow up, they typically find another, higher-brow sauce to have an inappropriate relationship with.

I chose tahini.

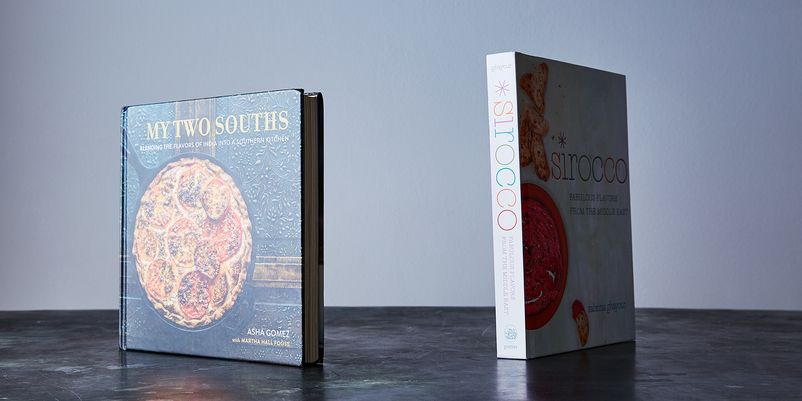

I say this only to reveal a built-in bias. When I first received my copies of Sirocco and My Two Souths—both filled with excellent recipes by cooks who have woven childhood flavors from faraway places (Iran and India, respectively) into the cuisines of their adopted homes—Sirocco was the easiest book to plug into my kitchen.

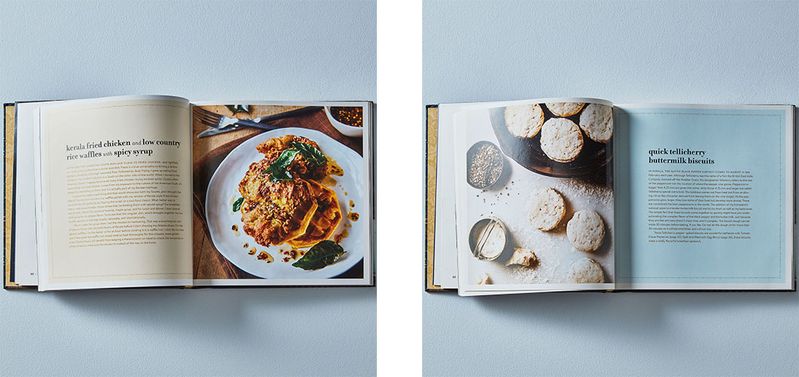

Like so many home cooks, it was Yotam Ottolenghi who made ingredients like tahini, za’atar, and harissa staples in my home, and whose recipes made dishes like lamb shawarma and sabih heavy-rotation hits, alongside my regular Now That’s What I Call Italian Food! playlist. It’s hard not to see Ottolenghi in Sirocco, and not just because I was looking (Sabrina Ghayour is based in London and is often mentioned alongside Sami Tamimi and Ottolenghi). Ghayour, who was born in Tehran in 1976 and moved to London in 1979, at the beginning of the Iranian Revolution, infuses a similar brightness—both aesthetic and gustatory—into her food. It’s evident in dishes like her spiced beet yogurt, which serves as Sirocco’s cover girl, a simple triumph of balance between earthiness, spice and sour, and her turmeric and spice marinated cauliflower, which I would truly not mind eating every single day. Likewise, her citrus and za’atar chicken—another study in sour and spice—has made no fewer than three appearances on my table since I received the book two months ago.

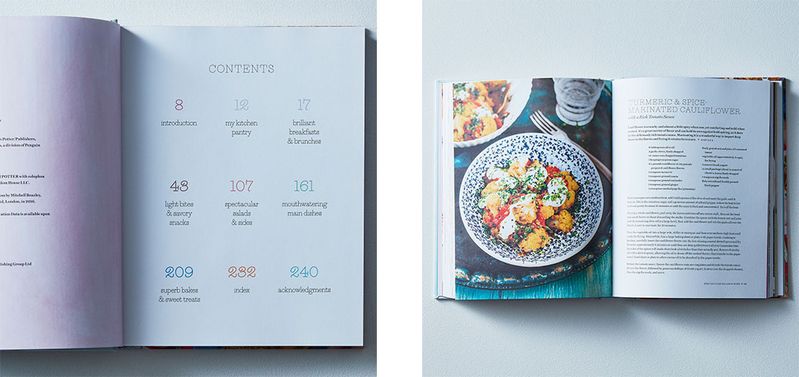

Sirocco is full of smart, beautifully photographed recipes like these (I also loved her cumin-roasted eggplant) that utilize flavors that are now familiar to many avid home cooks, but there is an underlying frivolity that sometimes comes off as pandering or trite. “Brilliant Breakfasts & Brunches,” “Spectacular Salads & Sides,” “Mouthwatering Main Dishes”—the Contents page is an indicator of the kind of language that hobbles the book throughout. I left it satisfied and full, but feeling starved for the substance and context of Ghayour’s first book, Persiana, which drew clear connections between traditional Middle Eastern flavors, their origins, and her interpretation of them. Sirocco often reads like a sequel struggling to stand on its own, lacking the depth and clear point of view that is requisite of a great cookbook, at least in my view, today.

Asha Gomez’s My Two Souths, by contrast, is a deeply personal exploration of the flavors of Gomez’s given home—the coastal South Indian state of Kerala—and her adopted home—Atlanta, Georgia—that touches on place, identity, and flavor. It is also, without explicitly saying so, an argument for the undeniable synergy between many southern cultures throughout the world.

Why is there a cultural handshake between the American South and, say, the Southern India? Or Southern Spain? It seems latitude is a powerful bond, but it’s much more than that.

Gomez supports this thesis from a culinary perspective by showing just how seamlessly vindaloo locks elbows with the nutty richness and familiarity of cornbread or how clove and curry leaves can take a Southern staple like fried chicken in an entirely new direction. (To my previous point, Gomez points out that fried chicken is actually a staple in both of her Souths: “Guests often assume that my fried chicken comes from my exposure to the cuisine of the American South. It’s always fun explaining to them that it is actually part of my Keralan heritage.”) I will probably never make cornbread without cardamom again, and I vow to never eat another waffle without Gomez’s Spicy Syrup—a combination of cumin and coriander seeds, crushed red pepper, and maple syrup.

When it comes to recipe writing, however, Ghayour is clearly more comfortable and adept; hers are detailed and easy to follow. My Two Souths required some improvisation on my part. In the headnote for the cornbread, for instance, Gomez extols the virtue of black pepper in the recipe, but the recipe itself does not call for it. The accompanying pork vindaloo called for a two-pound pork butt to be cut into 1/2 pound pieces (i.e. four pieces), but the accompanying image suggests that the pork had been cut into much smaller pieces before cooking. I googled the recipe and found an earlier version from Gomez in Garden & Gun that called for pork tenderloin, cut into a medium dice. I split the difference, and it was faultless—the sauce pungent from the generous addition of vinegar and garlic and the meat tender as advertised. It was unlike any vindaloo I’ve had in New York’s Curry Hill or along 6th Street; those “tongue-searing” versions, she explains, are distant relatives of the original dish, which was brought to India by the Portuguese. The next day I smothered a potato hash in it to excellent result.

Its pitfalls aside, My Two Souths is a compelling invitation into a kitchen that is singular in its perspective and striking in its ability to weave in ingredients like kodampuli and garam masala, but still read, firstly, like a cookbook about American Southern food. It is a testament to the very spirit of this country’s culinary present: American cooking is as much about mining our country’s past and indigenous flavors as it is about a cook like Gomez mining her own.

25 Comments

Fortunately for all of us, there are cooks out there who have used the book and taken the time to warn us of the problems. My thanks to them.

That said, I'm bewildered how cookbooks full of errors even are published. Can you imagine putting in the enormous effort required to create recipes and produce a cookbook book, and then not arranging for enough testing -- and reading in hard copy by other seasoned cooks who can spot potential mistakes -- before the manuscript goes off to the printer?

;o)