Maybe it’s heresy around these parts to say it, but not all cookbooks are meant to be cooked from. When done well, a restaurant opus can inspire in useful ways—and it ought to still be called a cookbook. But of late, the piling on of these books suggests an imitative cycle, an unearned effort to catch up with the Pattersons and Blumenthals. I’m running out of room on my coffee table. (I live in a studio in Manhattan and actually don’t have a coffee table, so I’m running out of room on top of my refrigerator and in that random gap between the ceiling and the kitchen cabinets).

So I was pretty happy to receive two deeply generous texts—Cal Peternell’s A Recipe for Cooking and Naomi Pomeroy and Jamie Feldmar's Taste & Technique—in the mail last fall, a delight that quickly turned to resentment when I remembered I had to pick only one to advance in this competition. I should also mention that coupled with that resentment towards the organizers of the Piglet was a humbling, intimidating feeling about attempting to write one of these things with a chef myself.

To the business at hand:

Peternell is the chef at the downstairs restaurant of Chez Panisse, a dining experience that’s slightly more involved than the storied café upstairs. As is the case with a lot of the free spirits that have passed through Waters’ campus, Peternell didn’t originally plan on a life in restaurants: He studied painting at SVA, in New York; it might explain the quietly exquisite sensibility of his work. His best-selling 2015 book, 12 Recipes, was designed for beginners and cooks looking to go back to the basics, setting up a dozen totemic models that each contained a bunch of variations. The New York Times Book Review deemed it “the best beginner’s cookbook of the year, if not the decade,” and Sam Sifton, in a rave, wrote, “The recipes are narratives, written conversationally, like excellent emails from a friend explaining how to make béchamel.”

For his follow-up, Peternell has opted for something slightly different: “This is a cookbook for when you want to cook more than what’s just necessary, for when you want to do some plotting and planning, plenty of stirring and peeling, and a measure of fretting over the little things,” he writes in the introduction. And so we have a very Panissian collection: the appetizers, first courses, sides, and desserts subdivided by season, the mains and sauces all clumped together, and the flavors all Californian, which is to say elemental Italian and French with comfortable gestures toward the Mediterranean, Asia, and other regions. Sadly, what we don’t get is a page number for each recipe, only for each section.

The recipes here have many of the same qualities that people fell for in 12 Recipes. Peternell will call for a “final swirl of olive oil, a last sprinkle of salt” (Fig and Sweet Pepper Salad); tell you to add “not quite 3/4 cup cold water.” (Pizza Dough Crackers); explain that you’re cutting the squash in half across “so you have a flat side to set it on” (Butternut Squash Panade); advise that you “tip off some of the fat if it seems ridiculous” (Chicken al Mattone); prevent you from cutting away “any of the soon-to-be-delicious skin” (Duck Cooked Two Ways); let you do it the “morning of, or day before” (Duck Cooked Two Ways, also); and instruct you to add the parsley only after the garlic and thyme start to “smell good.” (Corn Soup with Roasted Red Pepper and Wild Mushroom).

The headnotes accumulate nicely, providing scenes of a man, his family, and his colleagues living an enviable Berkeley life that doesn’t make you want to punch a wall. It’s inviting.

Peternell has a tendency for fabulism, which he signals from the very beginning by referencing the children’s book Frederick. This approach works when he’s talking about his fascination with mango and how its “skin color manages to mix green and red and come up with orange, which is, according to the color wheel I made back in high school, impossible,” or when he says, “cutting the meat from chicken leg bones takes some practice and a little x-ray vision, which believe me, you have.” The paragraph that precedes the dessert section, in which Peternell talks about his wedding, is especially moving. But it’s hard not to wince when he says that “good meals often yield good stories, and stories, on my list of life’s essentials, are right up there with food, air, and love,” or when he attempts humor: “…depending on how big your head is—of escarole, I mean,” and “Gelée is fun to eat and fun to say, like ‘gel, eh?’.” Lay off, dad!

I cooked through his yogurt-fried black pepper chicken (as he explains in the headnote, he always has yogurt in his pantry, but not buttermilk, a good point for those who share his tendencies or, if you don’t, a helpful tip), and the braised and grilled short ribs, both the kinds of preparations that are usually forgiving of my ineptitude. The short ribs is a lean recipe, barely four paragraphs, all you need to make it right. It includes one nice cue for the browning process: “Roast until they are nicely colored and smelling beefy.” The Chicken al Mattone was dead-simple and totally correct.

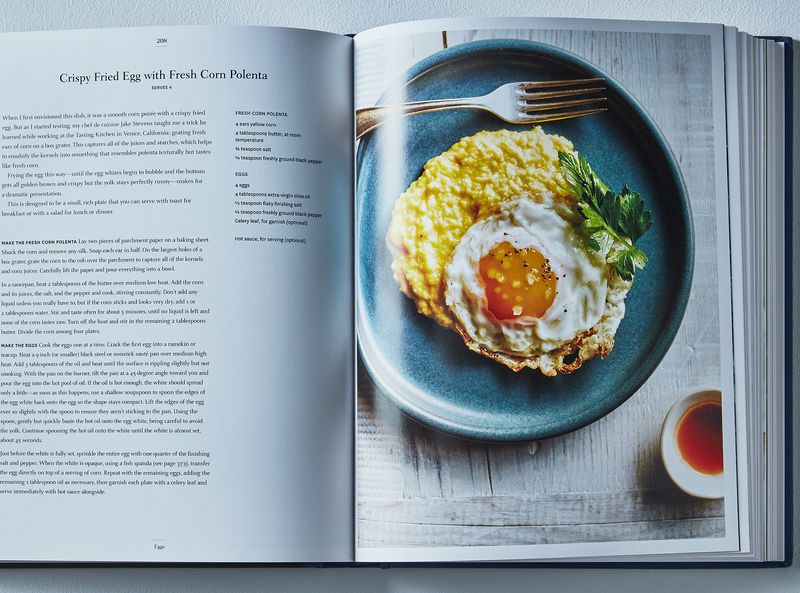

Pomeroy, the chef of Portland’s Beast, and her co-writer, Jamie Feldmar, does some storytelling, both at the beginning of book and in the headnotes, but all of the writing is in the service of Taste and Technique’s mission. The basic concept: a self-taught cook who learned her craft by reading Charlie Trotter, Gray Kunz, and Alice Waters finally writes a book of her own. It’s a nearly 400-page volume with everything you need to know about the fundamentals of French (or, some might say, French-American) cooking, with a straightforward organization, beginning with sauces, starters, and soups before moving into more substantial dishes and desserts.

You could treat Taste & Technique like a textbook if you wanted to. If you have the time, following the “curriculum” from beginning to end would probably make a novice into a well-rounded home cook. If you’re the type of person that worries about how much salt and pepper a preparation calls for, Pomeroy will tell you. But the neat part of the book is that it’s just as effective for those who want to be a bit more aimless and treat it the way you treat most other cookbooks: the lovely vagaries these works should almost always facilitate. It’s what I did. One night, I felt like making a romesco, so I tried hers. Among the teachings in Pomeroy’s romesco headnote alone is that “Mise en place is particularly important… once you get started cooking, [the ingredients] all come into play fairly quickly”. And after that, she doesn’t leave you hanging. Consider the amount of cues in just one paragraph of the recipe:

Cut the crust off the bread and cut the bread into 6 uniform cubes for frying. In your smallest saucepan (1 to 2 quarts or so), heat 1/4 cup of the oil over medium-low heat. Add the bread cubes, turn down the heat to low, and cook until the bread very slowly turns a deep golden hue on both sides, 15 to 20 minutes total. You want the bread cubes to be evenly crispy throughout with no softness or give. Don’t rush! If your oil isn’t truly slow and low, the sugars on the outside of the bread will caramelize and the bread will look done but the interior will still be soft. You’ll reserve the oil from this step and blend it back into the finished sauce, so it’s important that it doesn’t hit its smoke point and develop an unpleasant taste. (If it does, discard it and add a little more oil to your romesco during blending.)

And indeed throughout the book, Pomeroy and Feldmar prove that they know which tips should go in the headnotes and which are crucial to the procedure—introductions aren’t just storytime, and the recipes are far from cold prompts, making for a reassuring balance.

On another Sunday, I made Pomeroy’s balsamic glazed short ribs. At no point did I feel anything but the pleasure you should feel making short ribs on a Sunday. In winter, Pomeroy suggests pairing the ribs with horseradish gremolata (potato dumplings in spring; crispy brussels sprouts and pickled mustard seeds in fall). The payoff from the gremolata was minimal, but it did the trick of giving balance to the ribs, whose refined, focused flavor edged out Peternell’s more freewheeling approach.

For a book with so daunting an appearance—it really is, on first glance, less welcoming than Peternell’s—Taste & Technique affords the reader surprising flexibility. Seasonality isn’t the primary organizing force, and Pomeroy’s suggested pairings and variations, for which she provides recipes—it’s not a matter of this might be nice with a wedge salad and mashed potatoes—suggest an effort to make all the elements intertwine as much as possible. The result is a generative text that never overwhelms.

Had Peternell’s books been published a few decades ago, I bet Pomeroy would have had them stacked right next to The Elements of Taste and Chez Panisse Vegetables. I’ll be revisiting his painless, excellent chocolate soufflé recipe, since Taste & Technique’s section on the subject sticks to savory versions. And it’s much more involved, which is the point: In 2016, Pomeroy published the only book she would have needed when starting her career.

32 Comments

I have heavily gotten in buying cookbooks over the last 2 years and have several from Michelin starred restaurants. Some of those have only inspired me but I have cooked from all of them. Heston Blumenthal's books are amazing and his "Heston Blumenthal at Home" is perfection.

I felt like this was the first match up that made sense and I agreed with the outcome. Although there are plenty of cookbooks for starter cooks, basic cooks, and people who don't have a ton of time, I think it's important to also note people who buy the most cookbooks tend to be the ones who love to cook or bake and want to expand their skills and or techniques so a book like Taste & Technique excites me.

In my view, it is really a textbook and if one is a novice cook, this would be terrific. I am not sorry that I bought it, as it is packed with information, but compared to other cookbooks, the recipes contained herein are not as 'fabulous in flavour'.