My foray into The Piglet began in an appropriately competitive way, with a conflict of interest. I couldn't review the first proposed cookbooks because one of the authors is a pal, and I can't be objective when it comes to my friends. Which is too bad, because if there's one thing I'm qualified to discuss, it's Italian food, a lot of which was in that first book—it’s the cornerstone of my dietary preferences, culinary abilities, and genetic predispositions.

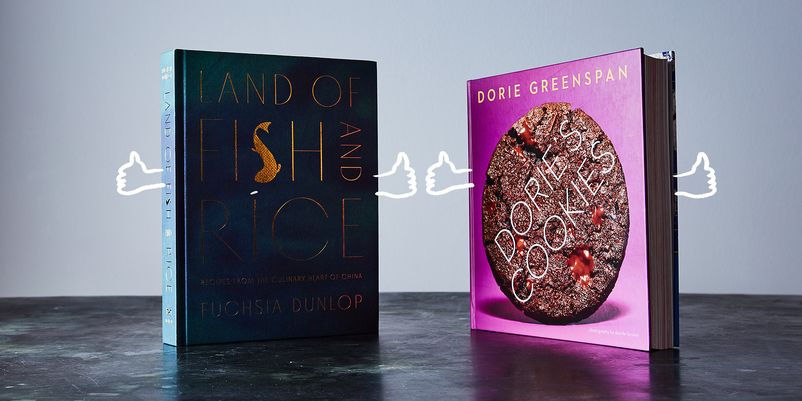

The next round of books, Fuchsia Dunlop's Land of Fish and Rice: Recipes from the Culinary Heart of China and Dorie Greenspan's Dorie's Cookies—posed the opposite problem, because I can't think of anything I'm less qualified to discuss than Chinese food and dessert.

Yes, reader, I am that rare glutton who has never liked either. And yes, yes—intellectually I know that the Chinese have given humanity one of the world's greatest and most storied cuisines. But in actuality, I have never, for all the times I have tried (and tried again), had a Chinese meal—of any kind, in any country, at any price point—that left me thinking, "damn, that was tasty." I know you're sitting there thinking, "you just haven't tried the right restaurant/dish/whatever," but I will counter that I have. I am a founder of the travel website Fathom, where one of our most popular sections is called "I Travel for the Food." Which is to say I have a professional interest in foreign cuisines. Yet although I want to like Chinese food because billions of eaters can't be wrong, I continue to fail at doing so.

As for cookies—come on, who doesn't like cookies? I can pretty much take them or leave them. (In contrast with, say, potato chips, which I can never, ever leave.) I have on occasion baked cookies, primarily biscotti at Christmas to give as gifts, because I love how excited people get to receive and eat them. But if I sample two of the batch of four dozen, that's a lot. Mine is not a sweet tooth.

So given that neither cookbook’s cuisine had a home court advantage, we were all on a level playing field.

The books have a few things in common. Their foods are global crowd-pleasers, and the authors are among the foremost authorities on their subject matter. London-based Dunlop has written five books on various Chinese cuisines, has won four James Beard awards, and was the first Westerner certified as a chef at the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine in China. Prolific Greenspan may be New York City's most beloved home baker, with her own mantle of Beard awards for her books and articles, and blogs and cooking clubs devoted to her. The ultimate manifestation of her cookie obsession may have been Beurre & Sel, the cookie boutique she ran for years with her son Joshua.

The similarities, however, end there. Land of Fish and Rice is a beautiful volume devoted to Jiangnan, the eastern coastal regions of China (aka the land of fish and rice), whose cuisine is "known for its delicacy and balance." In the opening essay, Dunlop doesn't attempt to hide her favor: "While every Chinese cuisine has its charms, from the dazzling technicolor spices of the Sichuanese to the belly-warming noodle dishes of the north, I know of no other that can put one's heart so much at ease as the food of Jiangnan."

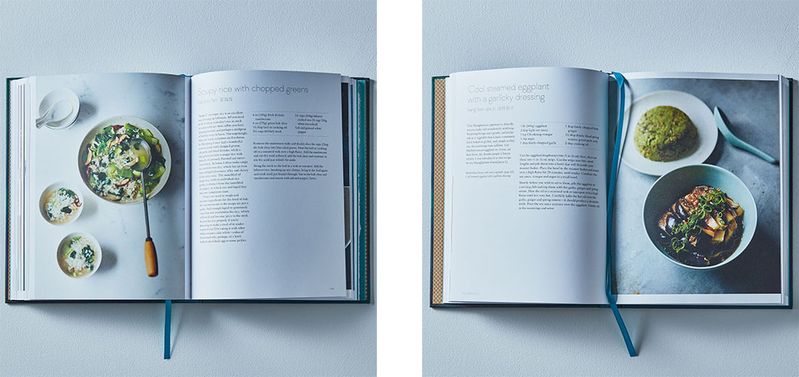

She maintains this loving literary tone throughout the recipes, which are illustrated with muted, overhead photographs of perfectly composed plates. A quick scan of the recipes reveals terms and ingredients that are new to me and not anywhere on my usual marketing rounds: Chinkiang vinegar and Shaoxing wine, dried lily flowers and bamboo shoots. Cooking from this book will require planning.

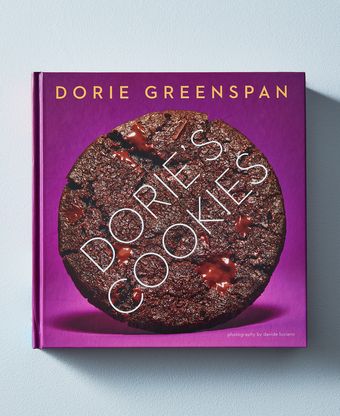

Dorie's Cookies announces itself with an altogether different tone, starting with its cover image—a giant chocolate cookie with melting chocolate chips against a bright purple background—and continuing through 500 pages of saturated close-ups of biscuits, crackers, bars, meringues, knots, nuggets, puffs, and jammers.

Reading through Greenspan's two opening chapters on techniques (organized with directives that may as well be her 20 Commandments of Cookies) and ingredients, I flip through the pages that follow, bookmarking a few dozen recipes that catch my eye. When I realize that many of the ingredients—flour, sugar, almonds, Parmesan, chocolate—are already in my kitchen, I start baking.

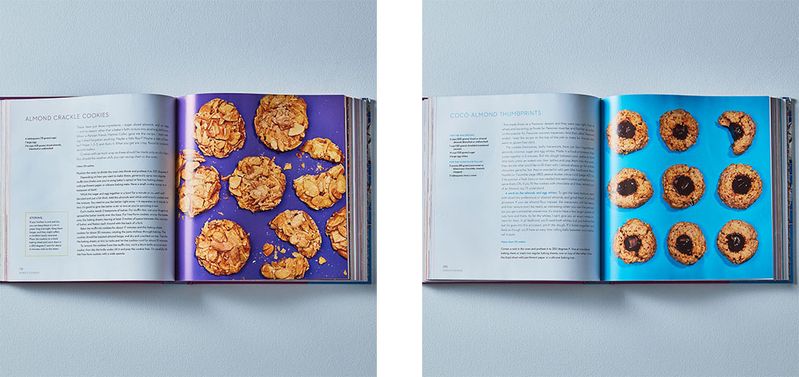

The recipes that make the final cut seem easy, interesting, and varied: Almond Crackle Cookies (p. 176, from the chapter "Cookies for Every Day, Any Day"), Coco-Almond Thumbprints (p. 288, from "Cookies for Weekends, Holidays, and Other Celebrations") and, to satisfy my salty tooth, Parmesan Galettes (p. 424, from "Cocktail Cookies").

The cute thumbprints consist of a macaroon base with a button of chocolate in the center, which can be replaced with jam or Nutella. The process is simple: Bake the cookies, then fill them when they’re cool. I make the cookies by whirling slivered almonds, shredded coconut, and sugar in the food processor, then pulsing in egg whites until the dough is squeezable. I drop little balls of dough onto a baking sheet and make a small indentation in the cookie. I like that Greenspan reassured me not to worry if the cookies cracked because "it's unavoidable." (It was.) I stabilize the cookies as suggested, and pop them in the oven. Preparing the filling involves melting chopped chocolate and heavy cream, and spooning the mix into the cookie's center. The recipe calls for doing this with a small spoon, but the process is a little messy, and I wonder if a pastry bag, were I to own such a thing, would have made for a neater process. The cookies are tasty, and are an especially big hit with my father, who takes a dozen to our family's restaurant to devour after dinner.

Parmesan Galettes are next. Again, the preparation is as easy as, er, pie: Pulse flour and cold butter in food processor, then add grated Parmesan. Then pour the dough onto a work surface, form it into a log, chill dough, slice, and bake. Dorie's tips for log-rolling involve wax paper, a ruler, and a tight process of pushing and pulling the dough. I would have liked a video of this, not to mention better wax paper, but I muddle through and end up with even slices. Twenty minutes later, they are done, and after ten minutes of cooling, I taste the first galette. Never mind a glass of milk: These demanded a glass of Prosecco. This is my kind of cookie! My father and husband agree. Pastry heaven. And so simple that I predict I will have this recipe memorized within two weeks.

I am feeling confident by the time I got to almond crackle cookies, a recipe from Dorie's Parisian friend Martine. Made from almonds, one egg, and sugar, they take about five minutes to prepare. Whisk egg and sugar, add almonds, scoop onto cookie sheets, bake until they're "toasted-almond beige." Well, in theory. Mine don't get as crispy as they should, cook unevenly, and fail to charm me. Did they falter in comparison with the Parmesan triumph? Maybe, but this isn't one I'll turn to again.

Off to a promising start, I feel ready for Land of Fish and Rice. But although it's an undeniably beautiful book, when I rifle through the pages, nothing jumps out at me. I read the opening chapter and find in Dunlop's lyrical prose about the "shady bamboo groves, silvery gleam of water, quivering green of new rice shoots" the inspiration and direction I need to approach Jiangnan cuisine. I will prepare food "known for its delicacy and balance" through dishes that do not "mask tastes in a riot of seasonings" and that use seasoning "not to overwhelm the innate taste of ingredients, but to enhance them with umami savoriness." I'm especially intrigued by food that "is cleverly engineered to tease and cheat the senses," and look for a recipe that fits this bill for my opening gambit.

I settle on Dai Jianjun's Vegetarian "Crabmeat," (p. 125) named for the owner of Dragon Well Manor restaurant in Hangzhou. The recipe calls for eggs, ginger, salt, pepper, sugar, oil, and vinegar. In theory, after everything is cooked in a well-seasoned wok and finished with vinegar, the eggs will evoke stir-fried crab. The instructions are easy to follow, and brief. Cooking time, including the prep work of chopping ginger, takes less than five minutes. When I finish, I put the mix into a dainty bowl I bought in India, and eat standing up in the kitchen. The dish is fantastic, the tang of ginger an unusual but not unwelcome note in eggs. I like this recipe, and suspect I will find it especially useful on mornings after I've had too much to drink.

Continuing the theme, I move on to Vegetarian "Crabmeat" (p. 209) made from shitake mushrooms, carrots, potatoes, eggs, starch, and, again, a combination of chopped ginger, salt, pepper, sugar, oil, and vinegar. This dish begins with soaking mushrooms in boiling water for 30 minutes, then slicing them very thin. In the meantime, I steam carrots and potatoes, and finely chop them when they cool. Salt, sugar, starch, and egg whites go into the potato-carrot mix. After heating oil in a well-seasoned wok and stir-frying the ginger and mushroom "until the ginger smells wonderful," I add the mash and stir quickly until the egg cooks. But I’m not fooled by the recipe title: I have made a vegetable hash, and not a particularly tasty one at that. The texture isn't appetizing; the flavors are flat. I wonder if my problem is my lack of a well-seasoned wok. I consider this every time I see the leftover container of this dish in the fridge, until I finally throw it away.

My next dish is Cool Steamed Eggplant with a Garlicky Dressing (p. 60). I cube the eggplant as directed, but am confused by the instructions to pile it into "a bowl that will fit inside your steamer basket." I have a steamer basket, but why can't I just steam the eggplant directly in that? I do as I'm told anyway. While the eggplant is steaming, I combine soy sauce, vinegar, and sugar in a bowl, and chop garlic, ginger, and spring onion. This is a dish whose magic comes together in the final minutes. That's when I sprinkle the chopped ginger mix over the steamed eggplant and pour the oil I have heated in that wok on top of everything so it produces "a dramatic sizzle." (Dunlop really is a vivid writer.) The soy sauce is the finishing polish.

Everything works perfectly. The dish is amazing. The serving could have fed four, but I devour the whole thing, grateful my husband doesn't like eggplant. I prepare the same dish a week later for my best friend and she asks for the recipe. I don't understand what the point of the bowl in the basket is, and will try again in future versions to prepare it without the bowl (as is probably obvious, I like to make things as easy as possible when I'm cooking). But there will be future versions. This recipe is incentive to always have an eggplant on hand.

Despite the vegetable mess, Land of Fish and Rice fares better than I would have expected. But the one I will turn to again and again and expect to splatter with butter in short order is Dorie's Cookies, which gets extra points for ease of use and humor. This is the book that delighted the senses more than Dunlop's, which more often delighted the mind. Then again, those Parmesan Galettes were a perfect ten of cooking, swaying the jury as no cool eggplant ever could.

96 Comments

For another, steaming the eggplant directly in the steamer would probably introduce a lot of unwanted water into the dish, as well as washing away some of the flavor. Plus, if you're using the traditional bamboo steamer, you're eggplant would pick up strange flavors, you'd have a mess to clean up, and your steamer baskets would't last as long.

I, too, am unexcited by cookies, except to cook them for parties and gifts, so I would have voted for Land of Fish and Rice. But Pavia gave both books a fair and thorough chance, so I have no complaints at the verdict.

Some things I have cooked from this book:

Cool steamed aubergine with a garlicky dressing

-I agree that this was fantastic. I've made it 3-4 times. It's also extremely easy and quick.

Eight-treasure spicy relish

-This is an amazing hodgepodge of bamboo shoots, chicken, pork, dried shrimp, soybeans, mushrooms, tofu, and peanuts, all chopped up small and bound together with a sweetish, funky sauce. Delicious hot or cold, by itself or spooned over rice.

Shaoxing "small stir fry"

-This dish, a simple stir-fry of bamboo shoots, preserved mustard tuber, pork, and yellow chives, was much greater than the sum of its parts. I see why it was the originator's favourite meal.

Ningbo Soy Sauce Greens

-The shrunken bok choy were incredibly beautiful and the stems were delicious. the leaves were extremely salty, I would try again with a lower-sodium soy sauce

Clear-simmered lion's head meatballs

-I hand-chopped the meat, as instructed. The meatballs were very soft (you simmer them underneath cabbage leaves so that they don't agitate so much that they fall apart) and very fatty. I made these as a main course but I think they would have been best served as a couple of bites paired with crisp, acidic foods. I think this is one of those dishes where the draw is the texture and I didn't "get" it. Textural emphasis is one of the hardest things about Chinese food to embrace as a Westerner.

Ningbo omelet with dried shrimp and Chinese chives

-This was not bad, but I prefer stir-fried eggs with tomatoes (see Every Grain of Rice for a recipe). The ratio of chives to eggs is a little too high for me.

Hangzhou Buddhist "Roast Goose"

-I made the stuffed version of this dish, which is layers of dried tofu wrapped into a parcel stuffed with a mushroom mixture, steamed, and fried, to be eaten sliced. I thought I understood the instructions but must have erred somewhere, because the tofu was too chewy to eat.

Clear-steamed sea bass

-This was quite subtle. It was impossible for me to arrange the ingredients on top as beautifully as in the photo. The ham shrank when heated, which ruined the symmetry! I preferred "Steamed sea bass with snow vegetable", which also had the benefit of being easier.

Stir-fried shrimp with Dragon Well tea

-The tea leaves paired well with the shrimp but there seemed to me to be a little too much starch coating in this dish. I think "velveting" is a skill that I have not quite mastered, and I wish Dunlop had included a technique section in the book, because she notes that technique is very important to the region's cuisine, but her instructions can sometimes be frustratingly vague.

Also, I thank the author for introducing me to Dragon Well tea! These are long thin spiky tea leaves that are delicious, almost savoury like chicken broth, with a bit of a sweet finish and very little bitterness. In fact, you can (and should) re-steep the tea over and over without it becoming too tanic. I can (and do) drink it all afternoon. (I found it in a Chinatown pharmacy.)

Stir-fried cabbage with dried shrimp

-My boyfriend goes crazy for this dish. He's become a huge fan of dried shrimp. The recipe for green bok choy with dried shrimp is also good, but the cabbage is easier because no blanching is required.

Stir-fried lettuce

-This is just lettuce, oil, and salt, so it feels a little silly calling it a recipe, but who knew you could stir fry lettuce? And who knew it would be so delicious! I used this method to use up half a leftover romaine just yesterday. Yum.

Lotus pond stir fry

-This was surprisingly good. All of the ingredients were crunchy, but in different ways (and they REMAINED crunchy when I microwaved the leftovers the following day! Hooray!). I also enjoyed the white-on-white look, with a bit of celery for contrast. I would like to serve this at a dinner party because it is impressive-looking but easy.

Bok choy broth with pickle

-This was easy, but boring. The pickle flavoured the broth, but lost its own flavour in the process.

Mrs. Song's thick fish soup

-A little involved but WELL worth the effort, I've made it twice and had seconds both time. It's a bit misleading to call it fish soup, because it's equally mushroomy and chickeny and hammy.

Stir-fried rice cake with scrambled egg and dried shrimp

-a good, simple, quick, pantry-cupboard sort of dish (if you have rice cakes in the freezer and bok choy in the fridge, as I usually do ...), but not spectacular.

Shanghai noodles with dried shrimp and spring onion

-Amazingly good. The scallions and shrimp add great flavour and texture. I added some leftover fish and the noodles just sang.

Shanghai potsticker buns

-These might be in my top 10 of favourite foods. The prep is a bit involved (you have to make dough, and jelled stock (using a pig's foot, but it's really easy, you basically just simmer a pig's foot) and filling separately, and then roll and fill the buns, and then you "stovetop bake"/steam them in a cast iron pan). They are liked baked shanghai soup dumplings. The pork is fatty, the filling is full of umami, the buns are crispy crunchy on the bottom and soft on top .... so so so so so so good. I want to make them again right now just thinking about them.

Probably the ratio of hits to misses is higher in "Every Grain of Rice", and I cook from it more often because the recipes are less involved, but this is a really great book and I urge you all to give it more consideration than did the author.

However, I'm more disturbed by Ms. Rosati's comments about Chinese cuisine. Given that she's a professional writer, and that Food52 is one of the main online outlets for professional food writing, I'm surprised something as simplistic as "I don't like it" would be considered an adequate reason to write off an entire cuisine. China, by the way, is made up of a vastly heterogeneous set of food cultures and traditions, so to dismiss them all as one unified idea of "Chinese food" is uninformed, in the context of professional food writing.

It is absolutely fine for people to have preferences, but if you're a professional writer, asked to judge cookbooks for Food52, shouldn't you at least cultivate a more educated engagement with the cuisine? I think this review is an embarrassment for Food52.

I will say that I voted for a 'rematch' on this particular pairing.

I also find it disrespectful that this review just wrote off the entire cannon of Chinese cuisine, and then tries to justify because she is a travel writer. This is just ignorant, and I'm seriously surprised that, as a reviewer, she doesn't realize the need to be professional about her disdain for an entire, enormous country's food. Then, there's the fact that she made it clear from the beginning of the review that she was not willing to seek out the ingredients needed to cook well from Land of Fish and Rice, despite the fact that she lives in New York and has presumably had the book for several months. In what world is this a fair review of this book? She cooked three recipes that seem to be chosen because they use few ethnic ingredients. Even though she ended up really enjoying two of the three, she had already stated at the start of the review that she doesn't like this cuisine and doesn't want to find the ingredients, so she used confirmation bias to justify not liking this book as much.

Dorie's Cookies is a gorgeous book, but this review did truly the bare minimum in reviewing LoFaR. Just like the Deep Run Roots review, it's sad that judges aren't picked who will give these big, in-depth books the attention they deserve. I don't really see what the point is in opening a conversation up about these disparate books when the result is so shallow.

As she explains in her write-up, we wanted to see Pavia take on TASTING ROME, because her heart/stomach/cooking style is rooted in Italy, but, alas, she had a conflict of interest. That's something we are sensitive to and always trying to avoid. I actually LIKE that we were "stuck" with this Plan B because, by presenting Pavia with two things she's equally indifferent to, we were able to level the playing field in a really unexpected way. I'd be more concerned, actually, if she LOVED baking and hated Chinese food, or was like a total har gao/dim sum snob and ignored all cookies all the time. Then we'd have an unfair disparity. In this case, though, there was a chance for a cookbook to change her mind; there was also a certain objectivity to be applied. She was open to being equally pleasantly surprised by either. One way to think about what makes a successful cookbook, is to ask, would someone who imagines they're not interested in or intimidated by the subject matter like this? What effect would it have on him/her? And as you can see, Pavia really warmed to both of these cookbooks--that's as ringing an endorsement as one could hope for. When she chose the winner, though, she was able to look at each the way any of us might look at a cookbook and ask, WHICH DO I WANT TO GO BACK TO? Take that for what you will. I think it's pretty cool.