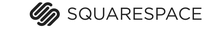

So you want a cookbook review? Here’s your [expletive-omitted] cookbook review. I’m standing by the kitchen sink, pouring hot water over the inside pages of two reasonably heavy tomes: Prune by Gabrielle Hamilton and Heritage by Sean Brock. I’m doing this for thirty seconds over each book, counting using the Mississippi method, because really, these hefty editions look like coffee table books, not working-in-the-kitchen books, and there’s no way they can stand the rigors of a tempestuous sink.

But guess what? The water beads off each with ease. There’s virtually no ink bleed. Within minutes, the pages are dry enough to continue turning. I can even pick up each one by the wet pages and shake them off like Taylor Swift shakes off her haters. And nothing rips. Well, nothing rips too badly. (Try that with your vintage copy of Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking and see what happens.) But alas, since I don’t review restaurants by throwing rocks at them, I thought all of you might appreciate a little content criticism as well. Here you go.

Let’s start with Prune, which refers to a very good restaurant of the same name in Manhattan’s East Village. Hamilton is gifted at pissing people off, and that skill, which she's cultivated and deployed with aplomb, comes through masterfully in her cookbook. This is when I tell you that Prune lacks a foreword, intro, or any type of usable index. I had a hell of a time finding one of the recipes after I closed the book while grilling. Ever try flicking through glossy pages with compound butter and raw meat on your fingers? Isn’t fun. All of a sudden you wish you had those more textured Julia Child pages back, don’t you?

What is refreshing, however, is Hamilton's lack of condescension. There’s no talk about this or that being too difficult for the home cook. Hamilton writes Prune in the voice of a "faux-manual" for her sous chefs. This is how our restaurant is run. That means the reader, dressed in stretchy yoga pants while lounging on a sofa (that’s me), gets to vicariously and safely enjoy the experience of being admonished in a sweaty professional kitchen over long hours and for little pay.

What’s even cooler is that Prune’s pages are peppered with a collection of no nonsense, handwritten notes. For example, when turning leek bottoms into decorative arrangements: “Crowd them a bit so it doesn’t look too precious or Martha Stewart-y.” I also liked the tip about avoiding "boiling crab gut" burns while making soft shells; I’ve been scorched while heating fish in hot oil before, though Hamilton clearly underestimates the value of showing off scars on first dates.

But even if she is writing Prune as a pretend manual for her restaurant, it appears as if she's more interested in having someone follow instructions rather than having a cook think for herself. That lack of context is no small matter. One of the most important things about the hospitality industry is that we should be teaching young chefs (and home cooks) powerful ideas and techniques that can shape the way they view food.

Not only do we not get enough of that greater world view from Prune, we don't consistently get it at the smaller, dish-by-dish level. No, not every entrée needs a 500-word story behind it (“my granddaddy made this during the siege of Leningrad and originally used dog brains”). But why is salt-crusting the best way to cook a tenderloin? What should tripe or beef heart or monkfish liver -- three ingredients that are relatively unfamiliar to home cooks -- taste like? It's not just a question of what someone might experience; it's a question of learning how offal should taste when it's fresh and when it's foul.

And why not give a reader some idea as to why one would use two parts chuck and one part lamb in a burger -- is it to tame the latter for those who don’t like its musky taste? (Sutton Tip: You’ll be fine with half lamb or even all lamb). Moreover, that burger recipe calls for “wall-to-wall” shallot butter on each side of the English muffin bun. Such a move would be smart to rescue a disastrously over-cooked patty; but with these well-marbled meats, the extra fat only creates a drippy mess (along with a postprandial feeling of deep personal shame).

The only larger lesson we really get from Hamilton appears to be her (brilliant) soliloquy on how to cook family meal, the pre-shift tradition at many restaurants where a chef is charged with feeding the rest of the staff, often using mostly scraps and leftovers. As so many Americans struggle to feed their sons, daughters, and parents, Hamilton gorgeously paints that daily, sometimes drudgery-laden task as an honor rather than a duty. “You start with nothing but a cauldron of boiling water and a stone and by the end of the story you have a rich meal filled with all the little bits that each villager was able to contribute.”

And at the more micro-level, to be fair, Hamilton nails it with her section titled “Garbage,” where she tells readers how to salvage spent Parmesan rinds by making stracciatella soup, how to rescue expired cream by making butter, and how to turn dirty celery into ragu. You get these pithy techniques condensed into 43 pages; offer that as separate book with the family meal section and watch it sell millions.

By the way, those who want to cheat around the lack of an index can download the book on iTunes and use the search function on an iPad. Otherwise, just make like a chef and fold the pages. Who gives a [bleep], right? Cooking is messy.

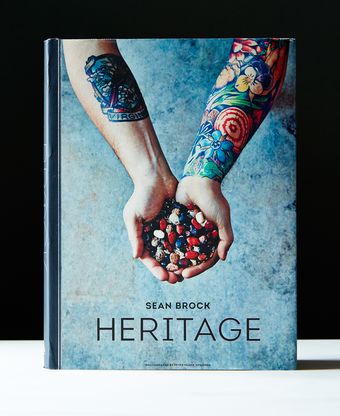

By contrast, Sean Brock, the chef behind McCrady’s, Husk, and Minero in Charleston, as well as another Husk in Nashville, has given us something different. He’s published not just a cookbook but a textbook on the diverse foods of the American South, with particular attention paid to the culinary differences between the mountainous region known as Appalachia and the maritime-inclined region known as South Carolina's Lowcountry. You could not cook at all from this book and you'd still learn the difference between a poussin, a roaster, a stewing hen, a capon, and a cock. You’ll learn how to age game birds safely (maybe).

You’ll learn that Brock sources his food from south of the Mason Dixon line, a political distinction that many Northerners don’t remember or recognize. You'll learn that Charleston, despite its gorgeous coastline, hasn't always had the best seafood and that if your local butcher doesn't have great rabbits, you might be able to find better ones via the classifieds. (Brock says he sourced one of the best rabbits he ever tasted from a trailer park.)

You'll learn how much effort goes into cooking grits (he recommends soaking them overnight!). You’ll learn how to appreciate bourbon and why you'll need five bottles of different proof for a cocktail party. You’ll also learn about why Brock loves Pappy Van Winkle, even though he fails to mention precisely how rare and gosh darn expensive it can be. In his Julian cocktail, he suggests using 2 1/2 ounces of Pappy, which at the prevailing market rate of $900 per bottle makes it a $79 drink. Hope you’re drinking alone!

Should you eat an amberjack? “These suckers are full of worms. But although the amberjack in Charleston’s warm waters may harbor parasites, the squeamish will miss out on a delicious treat. Soaking the flesh in a little salt brine overnight will drive out the worms.” Now you know.

Other questions remain. Why precisely must one slow-cook a pork shoulder for 14 hours when so many other cookbooks recommend shorter times? Why does Brock only recommend cooking with your "grandmother" if she's still alive, instead of your grandfather? (In my family, my dad did a lot of the cooking in my teens as my mom went to law school.)

When cooking grits: “After an hour, you’ll feel a textural change, and the grits will be very soft and tender. They will tell you when they are done -- it’s not something you set a timer for.” I’ll have to take the latter statement as being more true than the former, as I stirred for much longer than an hour, and my grits weren’t soft. (Disclosure: This was my first time making grits -- this Yankee grew up on Cream of Wheat.)

Also: Since Brock is so eloquent in (rightfully) tipping his hat to the culinary treasures that slaves brought over from West Africa (benne, cowpeas), perhaps it would've done him well to at least briefly acknowledge the horrors involved in the economies of human trafficking and involuntary servitude that plagued our nation (and the world) only a few generations ago.

That all said, as much as I love Hamilton’s use of the acronym “OMFG” (a coarser version of OMG), I learned so much more from Heritage than Prune. His book has a larger worldview that better serves both the home cook and the professional cook looking to understand why we eat the way we do in America, so Brock gets my winning vote. Though in all fairness, I should disclose that while I doused both books in water, I reviewed them without having subjected them to the all important blowtorch test. Forgive me. I’m new at this.

61 Comments

Thanks!